Lawyer X throws back sheets on a life of crimes and passion

Nicola Gobbo was forced to dig deep to defend a career spectacularly bereft of ethics.

Nicola Gobbo was forced to dig deep into her romantic memory box and defend a career spectacularly bereft of ethics during her first appearance at the royal commission she so deceitfully triggered.

But it wasn’t a traditional appearance, rather a manufactured presence, with only her voice piped into Court One on Exhibition Street in Melbourne, minus any vision, as the questioning veered from the disgraced gangland lawyer’s days at Melbourne University to whether she had slept with a National Crime Authority investigator.

The secrecy surrounding her appearance had everything to do with her being a dead lawyer walking if the clients she cheated on ever get a chance to strike back.

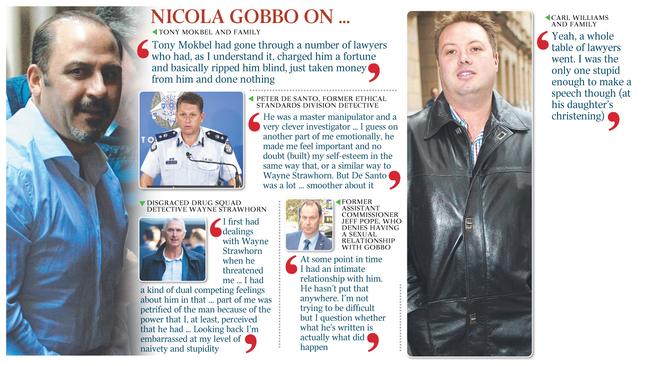

Inside the commission were lawyers representing a great cross-section of the Melbourne crime and crime-fighting community, from drug lord Tony Mokbel all the way up to former police commissioner Simon Overland.

Gobbo’s lack of a physical presence or even a TV screen showing her giving evidence made for a strange experience as the disgraced barrister fended off relentless questioning from counsel assisting the commission, Chris Winneke QC.

Day One of the cross-examination made it clear the commission is gunning for Gobbo after she was recruited by police to betray her clients, bringing the Victorian criminal justice system to its knees.

There were enough lawyers on the bar table to fill an entire Australian rules team, plus a healthy interchange bench, and several more sitting in the public gallery.

As with so much of this gangland soap opera, the subject matter was dense but the hours of interrogation weren’t without their lighter moments, particularly as Gobbo dealt with the question of who she had slept with while working as a lawyer and acting as a full-time informer. Her after-hours movements prompted an entertaining exchange where the supergrass, giving evidence from a location known to very few, wondered out loud about a National Crime Authority investigator she slept with more than 20 years ago.

Gobbo inquired to the royal commission about her former special friend from the now defunct NCA: “Is he balding, with blond hair?”

Royal commissioner Margaret McMurdo smiled and Winneke tried to get the show back on the road when Gobbo stretched deep into her memory, trying to recall the extent of the brief affair. As far as Gobbo was concerned, there wasn’t much in it.

“I wouldn’t go so far as to say relationship, Chris, but, yes, you’re right,’’ she said when asked about any closer-than-usual connection with the NCA investigator.

Winneke built a picture of a young Gobbo more than a little bit interested in police informants and more than a bit connected with the who’s who of Melbourne gangland crime.

She advised the Mokbel clan extensively, from Fat Tony to his brothers and more, worked for the killer Carl Williams and his father George (both dead) and the Moran clan, who were integral to the Carlton Crew. The commission has heard that during much of this time that Gobbo was acting for Melbourne’s criminal elite, she was talking formally and informally to three levels of the police: Victoria Police, the Australian Federal Police and, when it was going, the NCA.

Gobbo also relived a failed relationship with a drug runner when, aged in her 20s, she had become embroiled in police raids and scrutiny over his marijuana and speed trafficking.

By the third time she became an informer, Gobbo was well aware of the high stakes, telling her handlers that if they botched the relationship and she was killed, there would one day be an inquiry. “I would say basically, ‘If you people don’t know what you’re doing, I’ll end up dead and there will be a royal commission’,’’ she said.

For Gobbo, one out of two ain’t that bad.

In many senses, Winneke held Gobbo to account publicly for the first time after the force’s informants’ program imperilled the reputations of two former chief commissioners and the convictions of killers and drug traffickers.

Winneke spent most of the morning backing Gobbo into a corner, highlighting the ethical demands required of lawyers, principally to act in the best interests of their clients.

The commission heard how a younger Gobbo had developed a fascination with police informing and ethics, considering further study after completing her law degree.

Her strongest subject at Melbourne University law school had been legal ethics and she had investigated doing a master’s degree on the relationship between police and their informers.

“Looking back from where we are now, it’s laughable in a horrendous way,” she conceded.

When asked about the statement she made on the values she had to uphold when she became a member of Victoria’s Bar in 1998, she said: “Obviously … I have failed in that regard because look where we are.”