‘Keeping place’ plan to save Mungo Man for posterity

A plan to rebury the remains in unmarked secret graves had sparked an outcry from scientists and some Indigenous people.

The ancient remains that changed the world’s understanding of humanity may now be reburied in a dedicated “keeping place” that would preserve them for future study.

The bodies of Mungo Man and Mungo Woman, along with fragments from 108 other long-dead inhabitants of a remote area in what is now western NSW were to be reburied in unmarked, secret locations under a plan that was unanimously agreed by an Aboriginal advisory group back in 2017.

That process would have meant the remains would be lost forever, and sparked an outcry from scientists as well as some Indigenous people with ties to the area.

Heritage NSW has now started seeking public feedback around the potential for a dedicated “keeping place” for the remains, opening the door for an alternative reburial that would not lead to their destruction.

“The NSW government wants to hear from local communities, and the public, on an option of a permanent Keeping Place for those remains of Mungo Man and Mungo Woman,” a notice issued by Heritage NSW this month says. “Such a Keeping Place could involve reburial in a retrievable, controlled environment to provide for further scientific research.”

The Indigenous groups that decided on the reburial in unmarked graves declined to comment on the latest development, given they are due to meet in coming days to discuss the situation. They are, however, understood to be disappointed the NSW government is again intervening in the process.

Mungo Man and Mungo Woman are some of the oldest homo sapiens remains unearthed, having lived near Willandra Lakes at the height of the last ice age when megafauna still roamed the continent.

The well-preserved remains recovered from the region paved the way for Willandra Lakes to be declared a World Heritage Area, but has sparked decades of at-times divisive debate among Indigenous groups with links to the region over the best reburial options for the remains.

Several iterations of a dedicated keeping place were supported, studied and designed but none has come to fruition.

The unanimous 2017 decision by an Aboriginal advisory group set in train a process that would have seen the remains returned to the earth in the last few months of this year. Those plans were stifled when federal Environment Minister Sussan Ley determined they would need to be assessed under the Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act.

The Heritage NSW notice marks the start of that assessment, but the inclusion of a keeping place as an option is a marked departure from earlier approval processes.

While the plans for the unmarked reburials were endorsed by the Aboriginal advisory group, other Indigenous Australians outside that group have expressed opposition to the plan.

Native title determinations since the advisory group was formed have also raised questions over whether the group’s structure – including members of the Barkandji, Mutthi Mutthi and Ngiyampaa people – is appropriate. The only recognised native title claim approved in the area today is that of the Barkandji, and covers about 80 per cent of the area.

Barkandji member Michael Young told The Australian he and others strongly supported the concept of a keeping place, saying he believed members of the advisory group had been coaxed towards the cheaper option of an unmarked reburial.

Losing the remains to unmarked graves was comparable to last year’s destruction of the Juukan Gorge rock-shelters by mining giant Rio Tinto, he said, and would prevent Aboriginal people from studying them in the future. “We’ve got people in archaeology, we’ve got people in anthropology, we’ve got people in geology, all those areas which would benefit if we established that keeping place.”

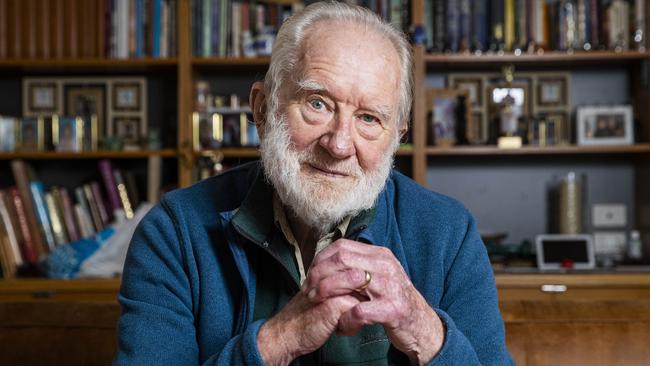

Geologist Jim Bowler, who discovered Mungo Man in 1969 and has long been advocating for a keeping place for the remains, told The Australian public consultation around the option was “surprising and very welcome”.

Burying the remains “with honour” in a keeping place, he said, would recognise their significance to all humanity.

“This is an amazing opportunity for the regeneration of that world heritage context in which the stories of land come together with the stories of people in a way which is without parallel elsewhere in Australia,” he said.

“Nowhere in the world do we have that conjunction of extraordinary landscape with natural process of erosion, revealing not only the stories but also the physical remains of people back to 40,000 years and probably beyond. It’s extraordinary.”

The consultation process will run until the end of January.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout