Keelty says Bali bombing created “unparalleled” co-operation between police forces

Mick Keelty weathered criticism in 2002 for insisting on time-consuming Interpol standards for identifying the bodies of Bali bombing victims, but he still insists it was the right thing to do.

Mick Keelty has always believed you make your own luck in policing.

So it was no accident that within hours of Indonesia’s worst terrorist attack on Bali’s nightclub district late on October 12, 2002, an Australian Federal Police post-blast forensics team was combing the smouldering ruins of the Sari Club and Paddy’s Bar.

The team was in Singapore when the bombs went off, en route to Indonesia to conduct training sessions for a national police force grappling with a new generation of militants, operating under the banner of Jemaah Islamiah, who had brought bomb-making skills home from the jihadist battle theatres of Afghanistan and The Philippines.

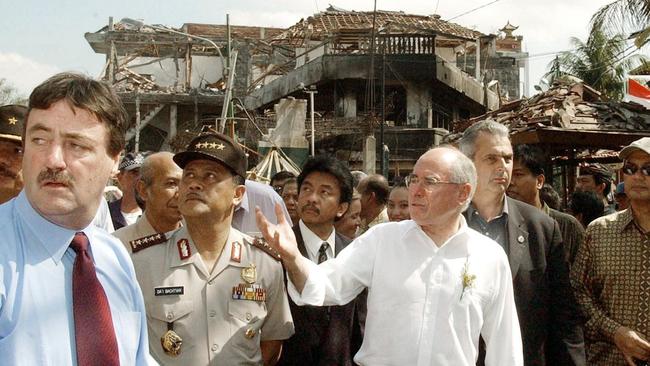

The then AFP commissioner had been working hard for months to forge a bond with his Indonesian National Police counterpart and in the early hours of October 13 the two men spoke by phone.

“D’ai Bachtiar said, ‘I need your people now’. I told him I could have them there in a few hours,” Mr Keelty, now an adjunct professor at Charles Sturt University’s school of policing and security studies, said the eve of the 20th anniversary of the Bali bombs. “That’s how the joint investigation started, because we had forensics people ready to go to the scene of the bombings.”

The “unparalleled” co-operation between the Australian and Indonesian police forces would ultimately extend far beyond the initial investigation, leading to a lasting counter-terrorism alliance that has helped both countries keep large-scale terrorism at bay.

But what AFP officers found in Bali would test the most hardened among them. Two hundred and two people died in the bombings, including 88 Australians, while hundreds more were badly injured. It was the deadliest peacetime attack on Australian citizens.

“It was like a war zone,” Keelty recalls.

“There was an engine of a car two blocks away on the second floor of a building. The crater left in the ground from the bomb that went off outside the Sari Club was metres deep. The fire hoses they brought in to put out the fires had created a well there.

“There were practical questions we had never had to face before.”

Keelty weathered criticism for insisting on Interpol standards – fingerprints or DNA – for identifying the bodies of victims, a time-consuming and traumatic process that some families still describe with bitterness today, but which he insists ensured far greater certainty amid some early mistaken identifications.

“We had to set up a whole network back in Australia to be able to identify people. We had to have all Australian coroners agree – for the very first time – what standard they would accept for people who had died in order to issue a death certificate, because a lot of things hang off that,” he said.

Among Indonesian and Australian police on the ground in Bali, there were also cultural differences to overcome.

The AFP insisted the area be preserved as a crime scene. Indonesian authorities were trying to clear the bodies so that Muslim victims could be buried within 24 hours, as the religion demands.

“As raw as it was, the bodies had explosive material on them,” Keelty says. “We had to work out how many suicide bombers there were.”

He credits then AFP Victoria chief Graham Ashton, a Bahasa Indonesia speaker, for smoothing over early difficulties and building trust with his Indonesian counterparts. “He had the confidence of the Indonesians. He spoke the language and it made a big difference.”

The work of both forces paid off; within a year, 23 bombers were tried, convicted and jailed for their roles in what to this day remains Indonesia’s largest terrorist strike.

Three ringleaders – Imam Samudra, Amrozi bin Nurhasyim and his brother Ali Ghufron (Mukhlas) – were executed in 2008.

While Indonesia suffered at least four more significant terror attacks in the next seven years, Keelty believes authorities there deserve more credit for shutting down JI as quickly as they did.

“It didn’t take a military intervention or international intervention like it did after 9/11. They did it using their justice systems and police investigations,” he says.

“They’re not going to boast about it because they have learned not to do that in counter-terrorism. You never want to claim you’re on top of it because the minute you do something will come out of left field.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout