Judges brawl over Afghanistan’s status

The courts are at odds over failed asylum seekers being sent back to Afghanistan, with judges issuing conflicting rulings on the status of the country under the Taliban.

The courts are at odds over failed asylum seekers being sent back to Afghanistan, with judges issuing conflicting rulings on the status of the country under the Taliban.

In one case this week, judge Gregory Egan of the Federal Circuit and Family Court rebuked a fellow judge for being “plainly wrong” for finding that Taliban-controlled Afghanistan no longer existed as a receiving country and it would be unreasonable to return anyone there.

A third judge, Kathleen Farrell of the Federal Court, held it was not open for her to take into account the re-emergence of the Taliban in Afghanistan.

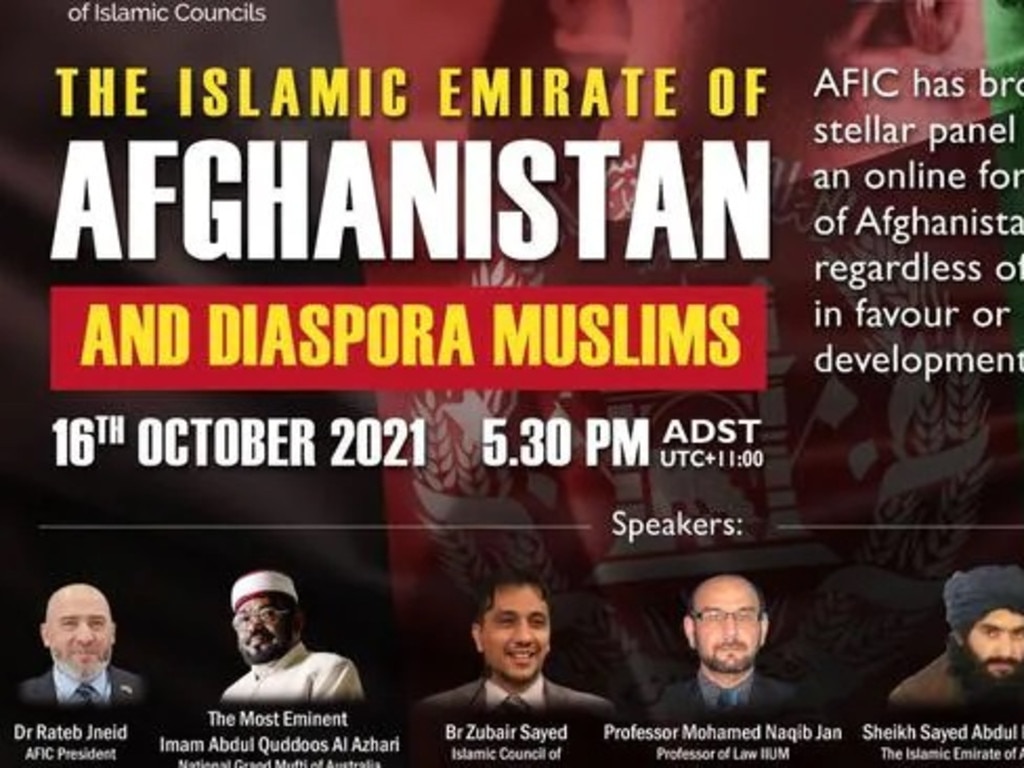

The decisions are not binding on the government and would be impossible to enforce if it came to deportations to the Taliban’s newly proclaimed Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, which Australia does not recognise. But the inconsistency among judges adds to the challenge for the federal government in dealing with a hardline Islamist regime in Kabul.

Immigration Minister Alex Hawke has pledged that none of the 8500 Afghan visa holders currently in Australia would be asked to return to the country while the security situation “remains dire”.

All three recent court cases involve ethnic Hazari Afghans who had been denied permanent refugee protection in Australia and professed to fear of persecution by the Taliban if they had to go back.

In the Federal Circuit Court last month, Judge Alexander “Sandy” Street found that the downfall of Afghanistan was a “jurisdictional fact” and the reconstituted Islamic state was a new and different entity which had to be factored in asylum cases. The construction of the decision by the government’s Immigration Assessment Authority concerning a “country that no longer exists” was illogical, irrational and legally unreasonable.

Ordering a fresh review of the Hazara man’s claim for protection, Judge Street held: “The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan is a different country, a different relevant state and a different receiving country.

“This text and the clear humanitarian purpose of the protection visa provision in the (Migration) Act support the construction that the existence of the country or receiving country is a jurisdictional fact.

“What Australia as a sovereign nation may or may not recognise as a foreign state is not relevant to or determinative of the application in these proceedings.”

But Justice Farrell, in a September 29 judgment dismissing the appeal of the second Hazari against another Federal Circuit Court judge’s decision to uphold an adverse IAA finding, insisted that the Taliban takeover was not a consideration.

“It is now well known that by late August 2021, the Taliban had gained control of Kabul and most of Afghanistan during the final withdrawal of international armed forces from Afghanistan,” she said. “However, it is not open to the court to take that fact into account on this appeal.”

Judge Egan’s criticism of Judge Street’s September 2 decision, which he said “emboldened” the asylum-seeker who came before him, is highly unusual. Judges of the same court rarely criticise each other’s decisions so stridently.

In this case, the Hazara man, 24, had arrived by boat on Christmas Island in October 2012 after setting out from Ghazni Province, where he claimed both his father and brother had been murdered by the Taliban. Judge Egan noted that IAA had uncovered inconsistencies in the man’s account.

His lawyers argued that the denial of his application for protection and dismissal of subsequent appeals against decisions by the Immigration Department and the IAA were unreasonable, and they sought a fresh review to take into account the Taliban’s return to power.

In rejecting the application on Wednesday, Judge Egan said of Judge Street’s ruling: “With the greatest respect, this court is of the opinion that the learned primary judge’s decision … was plainly wrong.

“First, though, it is well accepted that for reasons of judicial comity a judge should usually follow the decision of another judge of the same court, there is an exception where a judge is of the view that an earlier decision of another judge, based upon the same, or substantially the same facts, was plainly wrong.”

Judge Egan said he accepted the government’s submission that the only relevant jurisdictional fact was the “decision maker’s level of satisfaction or non-satisfaction” with an asylum-seeker’s claim for protection. He pointed out that the minister, in this case Mr Hawke, had discretion to approve a further application based on changed circumstances.

Sarah Dale, the centre director of Sydney’s Refugee Advice and Casework Service, called on Mr Hawke to intervene and end the uncertainty of judges “being left on their own to interpret” jurisdictional fact on Afghanistan.

“As a lawyer practising in this field, I can tell you just promising not to deport people for the time being is not sufficient,” she said.

After the fall of Kabul in August, Australian Human Rights Commission president Rosalind Croucher called on the government to reassess all Afghan asylum-seekers who had not received permanent protection, an option open to the Immigration Minister.

About half of the 8500 Afghan visa holders in Australia are on temporary protection or safe haven enterprise visas.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout