Woolly claims on insulation

FAR from cutting energy use, home insulation may cause it to rise.

FAR from cutting energy use, home insulation may cause it to rise.

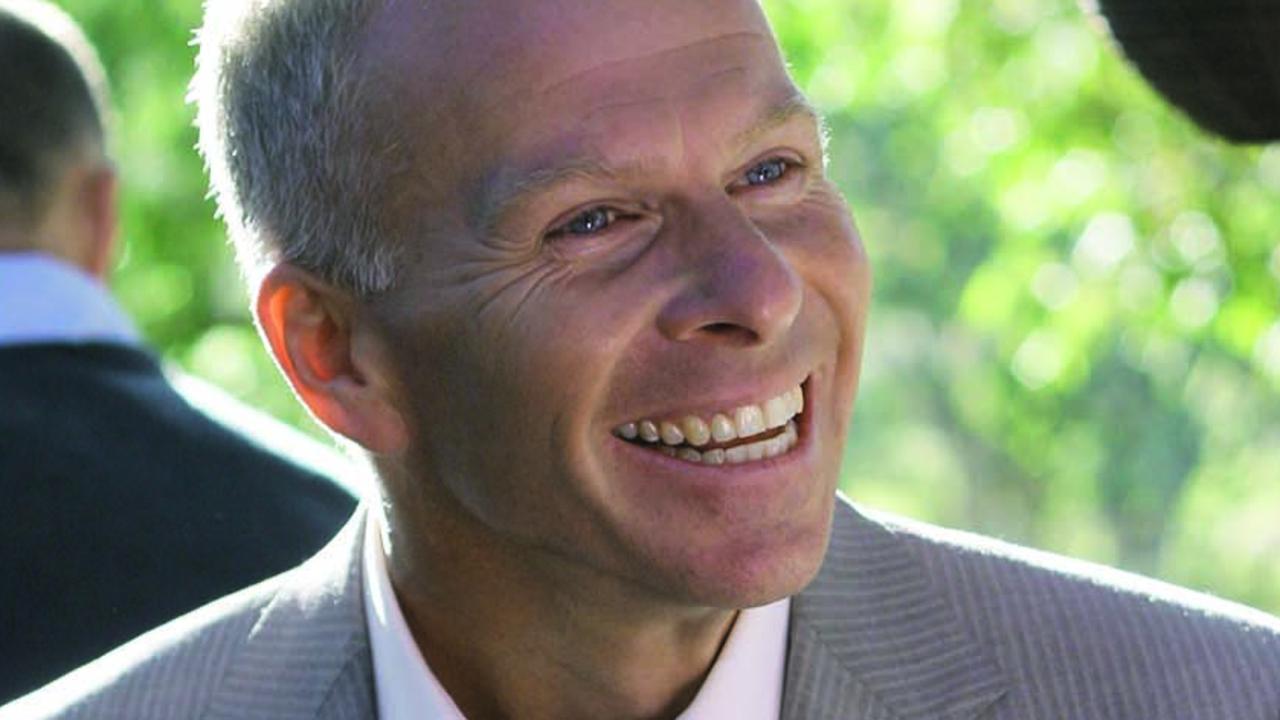

FOR much of his long career studying energy, thermal performance and sustainability in homes and buildings, Terry Williamson has searched for inescapable proof that could justify the widespread use of home insulation.

But the most worrying feature of his life's work, as the associate professor of the school of architecture at the University of Adelaide tells The Australian, is that peer-reviewed evidence proving ceiling insulation lives up to grandiose claims -- that it leads to a reduction in home energy consumption and a drop in greenhouse gas emissions -- does not exist.

His point is not that insulation does not have a role in cooling or heating a home. Clearly, he says, insulation can achieve these objectives if used holistically. But in practice, this is not what happens. The behaviour of the occupants of insulated homes determines whether the insulation has reduced their energy consumption.

Williamson is quite sure that after getting insulation, people tend to increase their comfort levels by buying airconditioning, or working their existing airconditioning harder.

Similarly, in winter, people with insulation tend to increase the use of their heating systems to make their homes more comfortable.

According to Williamson, insulation most likely precedes an increase, not a decrease, in energy use in households. The savings that are often touted are, he believes, a furphy in most cases. Households in Australia have been using more energy, not less energy overall, after being insulated.

He is also sure that one of the outcomes of the Rudd government's botched scheme to retrofit insulation in more than 2 million Australian homes will be a spike in greenhouse emissions, as occupants respond to a phenomenon known as comfort creep or rebound.

Williamson's submissions, papers and oral evidence to agencies including the Productivity Commission are unpalatable to Australia's multi-billion-dollar insulation industry, its most visible lobbying group, the Insulation Council of Australia and New Zealand and the Rudd government.

ICANZ and its consultants have argued against his conclusions. In the absence of a proper contemporary study of the practical before-and-after impacts of home insulation on the energy consumption of households, neither Williamson nor the industry can be certain.

During the Productivity Commission's 2005 inquiry into energy efficiency, Williamson developed a submission, titled A Plea for Evidence-Based Policy Making, in which he pointed out the lack of research into some of the claimed benefits of insulation and other products. His work posed a fundamental question: "What evidence exists to demonstrate a causal connection between the construction elements of a dwelling (for example thermal insulation, shading) and relevant aspects of energy-efficiency?"

He argued: "A blind spot is evident in policy-making where it is assumed that the results of computer simulation equate to reality.

"Real household energy use behaviour and the virtual-reality results of computer simulation are seen as one and the same when nothing could be further from the truth."

Inquiry chairman Neil Byron describes Williamson's submission as "extremely well-argued and well-supported", adding that the most important message was the prevalence of regulations and codes dedicated to sustainability and energy efficiency "without a great deal of evidence that it works".

Five years later, as Prime Minister Kevin Rudd and Environment Minister Peter Garrett work to reconfigure the home insulation scheme, Williamson asks: "Can anyone point to some evidence that we have not just poured countless millions of dollars down the drain?"

His research into insulation can be traced back to 1974-75, when he wrote his first paper on thermal performance for houses and, as a Housing Department employee during the Whitlam government, helped establish an association for the insulation industry.

"There is this general belief that if you do things like putting in insulation it must be good, that it must have the right effect in the end," Williamson tells The Australian. "Where people get this belief from, I have no idea. The claimed benefits from insulation are all based on theoretical things, not hard evidence. But governments do not want to know about it."

Williamson also doubts the effectiveness of computer models used to demonstrate insulation's benefits.

"Of course, the computer simulations are just applying physics," he says. "The computer simulations have assumptions in them about how people use heaters and coolers without evidence of what's actually going on in the home.

"The computer simulations assume people work like thermostats in buildings. People do not work like thermostats."

In practical terms, comfort creep or rebound, insofar as insulation is concerned, means that people who have had it installed in their ceilings then go further, boosting their airconditioning on hot days and their heating in winter. In doing this, their energy consumption increases.

"What people often tend to do is cool one room with airconditioning. But after they get insulation, they find they can cool a bit more of the house with the same airconditioner by turning it up a bit more," Williamson says.

"If your house is not airconditioned and you insulate it and you do not shade your windows, your house will get hotter. That's because you would keep that heat in and you would be actually hotter in the room, and people then go out and buy an airconditioner to deal with that."

He says a family with a blower heater working in just one room would be likely to run the heater harder if they had their house insulated, as additional rooms could then be heated.

Steve King, a specialist in sustainable development, author of Building for Conservation and senior lecturer in built environment at the University of NSW, is adamant Williamson is correct.

"Are the claimed benefits of insulation substantially overstated? I would agree, yes," says King. "The real benefit is that in poorly designed houses, insulation will get you better thermal conditions, but not by reducing energy; you will probably spend more on energy.

"So you are going to use more energy than before but you are

going to get better conditions for it. Insulation is not lowering greenhouse emissions.

"Insulation makes better comfort more affordable; it makes better conditions more affordable. Because we think it is more affordable, we spend more money (on appliances like airconditioning) and use more energy on getting these conditions."

In the lead-up to Garrett and Rudd rolling out the scheme, millions of dollars were spent by ICANZ's only two members, publicly listed companies CSR and Fletcher Insulation, which between them control 70 per cent of Australia's home insulation market, in a campaign directed at the federal and state governments.

Dennis D'Arcy, a former marketing manager of one of the companies owned by Fletcher, and Ray Thompson, the present marketing manager for CSR's insulation division, are the public faces of ICANZ.

Behind the scenes they have run a commercially successful and carefully orchestrated bid to sell insulation to the biggest single customer, the federal government, via a rebate scheme for households.

It was ICANZ that proposed to the government that rebates would provide the means and the stimulus to encourage widespread household demand for insulation.

In its efforts to put the products of CSR and Fletcher in as many Australian homes as possible, ICANZ commissions economists and computer modelling experts from consultancies, including Deloitte, to produce weighty reports extolling insulation's virtues.

These reports consistently say that the installation of ceiling insulation leads to a reduction in energy consumption and a reduction in greenhouse emissions.

The most powerful ICANZ-Deloitte report, titled "An economic assessment of the benefits of retrofitting some, or all, of the remaining stock of uninsulated homes in Australia", was provided to the Environment Department and Garrett.

In February last year, after Rudd and Garrett announced the national retrofitting scheme, D'Arcy, speaking as ICANZ chief executive on behalf of CSR and Fletcher Insulation, said: "The federal government has recognised that immediate and affirmative action is needed if we are to achieve significant and long-lasting benefits.

"Retrofitting Australia's 2.2 million uninsulated homes with effective ceiling insulation will reduce the need for additional power generation capacity and help to smooth out peaks in energy demand.

"Insulating homes also will deliver direct benefits to the environment through significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions."

It was a great day for the insulation industry.

Rudd explained on February 3 last year that the Energy Efficient Homes investment would "cut around $200 per year off the energy bills for households benefiting from these ceiling insulation programs" and "reduce greenhouse gas emissions by around 49.4 million tonnes by 2020, the equivalent of taking more than 1 million cars off the road".

"Insulation is typically the most cost effective way to improve a home's energy efficiency," Rudd said.

Williamson has been hearing statements such as these throughout his career. He drills into the data, reports and references cited by the insulation industry and the government.

Yesterday, while reviewing the ICANZ-Deloitte study , Williamson noted an acknowledgment in the report stating: "Moreover, the estimates of energy and greenhouse gas savings do not take into account the possibility of comfort creep."

The ICANZ-Deloitte study goes on: "That is, the perceived tendency of householders to increase their minimum comfort requirements following the application of building shell improvement measures.

"Such improvements in comfort requirements could take the form of changed thermostat settings and or an increase in actual conditioned floor area."

Says Williamson: "In other words, the estimates will be extremely exaggerated.

"They then go on to say, `there is no hard data in the form of post-occupancy surveys that would support an estimate of the likely impact of this phenomenon (comfort creep)'.

"In other words, there is no hard data so let's just make something up. In the academic world, this would be laughable."