Twist in tale of two accused of Kim Jong-nam assassination

Are the Kuala Lumpur airport ‘killers’ subject to double standards?

In the leafy laneways of Sindang Sari, an Indonesian hamlet more than two hours’ drive west of Jakarta, villagers were busy preparing food and banners this week to welcome the return of a prodigal daughter.

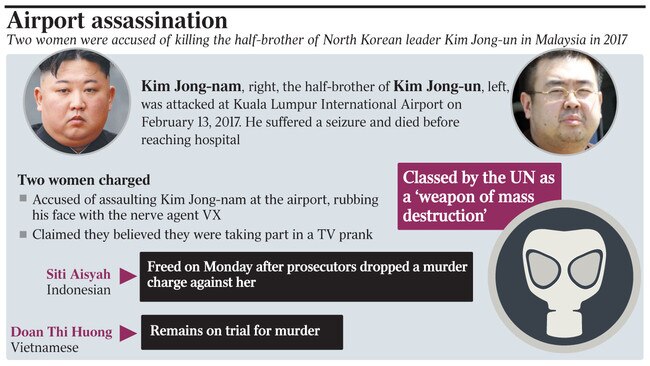

Siti Aisyah left Indonesia as a teenage divorcee and mother seeking ways to support her young son, only to end up an unwitting pawn at the centre of a Cold War-style assassination of Kim Jong-nam, 45 — the estranged half-brother of North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un.

In any other circumstances, Siti’s return to her conservative Muslim village in Java’s Banten Province after labouring in Malaysia’s shady massage industry would have generated markedly less goodwill.

But a Malaysian judge’s surprise decision this week to drop murder charges against her, more than two years after she was arrested with a Vietnamese woman on suspicion of carrying off one of this century’s most brazen political murders, is being portrayed as a national triumph for Indonesia.

Diplomatic win

Minutes after Siti, 27, walked out of the Shah Alam courthouse on Monday morning, her hair covered with a red scarf and smiling broadly, Indonesian government officials hailed her release as a direct result of diplomatic efforts at the highest level.

“This effort has always been raised at every bilateral meeting between Indonesia (and) Malaysia, including at the level of the President, Vice-President, as well as regular meetings between the Minister of Foreign Affairs and other ministers with their Malaysian counterparts,” said Rusdi Kirana, Indonesia’s ambassador to Malaysia.

A March 8 letter from Malaysian Attorney-General Tommy Thomas to Indonesian Justice Minister Yasonna Laoly appears to support that claim.

It advised that prosecutors had been instructed to drop charges against Siti in view of “the considerations you have mentioned and taking into account the good relations between our respective countries”.

Left in the dock

Siti’s release leaves her co-accused, Doan Thi Huong, alone in the dock, Malaysia’s criminal justice system open to accusations of political interference, and Hanoi — which hosted the second summit between Kim Jong-un and US President Donald Trump on February 27 and 28 — looking like it did not lobby hard enough.

Vietnam’s Foreign Ministry insisted on Monday that it had taken “active” measures to protect Doan’s right to a fair trial, including footing the bill for legal counsel. But by Tuesday, Foreign Minister Pham Binh Minh had called his Malaysian counterpart asking for Huong to also be released, Vietnam media reported.

Doan, 30, an aspiring television star, sobbed when the judge announced Siti was to be released, and was unable to proceed with her statement, prompting her lawyers to seek an adjournment until today to give them time to apply for her murder charge to also be dropped.

“I do not know what will happen to me now. I am innocent — please pray for me,” Doan said after Siti was led from the court.

In the northern Vietnamese province of Nam Dinh, her shocked father, Doan Van Thanh, struggled to understand why his daughter remained behind bars.

“Why did they release the Indonesian girl without releasing my daughter?” he asked.

Doan’s lawyer Hisyam Teh Poh Teik was asking the same question in Kuala Lumpur and told The Australian he was urgently lobbying the Vietnamese government through the Vietnam Bar Association to make similar approaches to Malaysia for their citizen’s release.

He has also written again to Malaysia’s Attorney-General to seek his client’s discharge.

“The defence by both parties was exactly the same. There’s no material difference between Siti Aisyah and Doan Thi Huong’s cases, so we can’t understand the discrimination. Why was justice given in one case and not the other when the defence was exactly the same in court and during the investigation?” Hisyam says.

“The Attorney-General issued a statement saying (Siti’s release) was done at the request of the Indonesian government, but the parties must be equal before the law — whether you’re Indonesian or Vietnamese — so we are hoping against hope that he will look at the file of Doan Thi Huong and come to a just conclusion.”

With just a month to go before Indonesia’s presidential and legislative elections, Siti’s release is undoubtedly a public relations coup for President Joko Widodo, who was happy to have a large media pack capture his meeting with the grateful young mother and her parents at the presidential palace in Jakarta on Tuesday afternoon.

A village rejoices

On Tuesday night, the entire village of Sindang Sari banged tambourines and chanted prayers in the rain to welcome Siti home as she arrived in a big black government car surrounded by police.

Lost in the euphoria of one woman’s return, however, is the likelihood that those responsible for the excruciating death of an innocent man, once considered heir to Pyongyang’s brutal Kim dynasty, will never be brought to justice. And that Kim Jong-un, the international pariah who intelligence officials across the Western world believe ordered his brother’s murder, has suffered no consequences for his actions.

It seems hard to credit now given the dictator’s reinvention over the past year, but the brazen assassination of Kim Jong-nam by the deadly VX nerve agent as he walked through Kuala Lumpur’s budget international airline terminal on February 13, 2017, helped spark an international crisis some feared could destabilise the uneasy decades-long truce between the Koreas.

At the same time as nuclear talks between the US and North Korea stalled, China cut off coal imports from North Korea — a critical income source for the regime — and Malaysia put its diplomatic relationship with Pyongyang in deep freeze as it struggled for ways to show its displeasure without provoking a brinkmanship contest with the unpredictable Kim.

Experts on the North Korean regime interpreted the assassination at the time as a warning to the international community of what could happen if you crossed him.

Kim’s kill list

Kim Jong-nam had confided in friends he feared he was on borrowed time, and that his estranged half-brother would get him in the end.

The portly father of four, who lived in exile with his second family in Macau, apparently under Beijing’s protection, knew he was on Kim Jong-un’s kill list for having years earlier publicly questioned the family’s hereditary rule and Jong-un’s fitness as leader.

He had become more fearful since a 2012 attempt on his life and the execution for treason a year later of Kim Jong-un’s close adviser and uncle Jang Song-thaek, along with hundreds of associates.

Even so, he was unlikely to have been anticipating trouble when he was approached by two unassuming young women at the busy Air Asia check-in kiosks at KLIA2.

In grainy CCTV footage shown in court at the trial of Siti and Doan, the two women are seen hovering near Kim Jong-nam as he checks in for his flight to Macau. One woman, alleged to be Siti, steps in front of him while another, said to be Doan, grabs him from behind and sprays a liquid in his face, which she then covers with a cloth.

The substance was believed to be the deadly VX nerve agent.

Kim Jong-nam then reels away from the check-in kiosks and towards the information desk, where he is helped down one floor to the KLIA2 medical clinic.

He slumps in a chair as the world’s deadliest nerve agent works his heart to exhaustion.

A nurse and doctor administer oxygen and hurry him into an ambulance but he is dead before he reaches the nearest hospital.

Lawyers for Siti and Doan insist neither woman knew anything of a plot to murder Kim Jong-nam and were unwitting pawns in a political assassination clearly linked to the North Korean embassy in Kuala Lumpur.

Intent to kill is critical to any murder charge in Malaysia.

Both women told police they had been recruited to work on a reality television show in which they played practical jokes on strangers, and had no idea that the substance smeared on their latest target — one of a number in recent weeks — was deadly.

Their lawyers insist they had never spoken before they met in a Kuala Lumpur police station on February 16, 2017.

The prosecution alleged they were recruited and trained by four North Korean men, who supplied them with the banned VX chemical weapon that they knowingly smeared on Kim’s face before rushing to separate airport toilets to wash it off.

The four North Koreans left the country within a few hours of the murder.

Another three North Koreans, including a chemist, suspected of involvement in the assassination, were allowed to leave Malaysia after hiding out for six weeks in the North Korean embassy.

The Malaysian government was left with little choice but to trade their freedom, and the body of Kim Jong-nam, for that of a group of Malaysian diplomats and their families held hostage in Pyongyang during the diplomatic crisis.

Siti’s lawyer Gooi Soon Seng says the decision to allow the North Koreans to leave the country fatally compromised the defence case, but that there was also no evidence linking Siti to the poisoning.

While the trial heard traces of VX had been recovered from Doan’s fingernails and the shirt she was seen to be wearing in CCTV footage at the budget airline terminal that day, Gooi said no such traces were found on Siti or on her clothes.

There was no conclusive evidence it was even Siti in the CCTV footage, he said, and none that clearly showed her smearing any substance on Kim Jong-nam.

“Once the prosecution completed their evidence we found it was rather weak, so we asked the Attorney-General to reconsider the case,” he says.

“Although we were very confident Siti would eventually be acquitted, the government would have likely appealed, which meant the poor girl could have suffered another two years in prison.

“So we impressed upon them that they had to review the case, especially considering important witnesses were allowed to return to North Korea, which compromised her defence.

“Along the way we also impressed upon the Indonesian embassy and ministry of foreign affairs the importance of using their goodwill to make representations on a government to government basis.”

While acknowledging the joint effort, he insists: “I don’t think the prosecution would just withdraw a case based on political considerations.”

Politics at play

In fact, political considerations have dominated every step of the investigation into Kim Jong-nam’s murder — a crime Malaysia has carefully avoided publicly linking to Pyongyang.

North Korea continues to deny official involvement, notwithstanding South Korean media reports that Pyongyang’s Foreign Minister informally apologised for involving a Vietnamese citizen during his visit to Hanoi in December.

Two years after the assassination, the US and North Korea have pulled back from the brink of war.

Pyongyang and Seoul are enjoying a growing rapprochement that critics say far outpaces progress on nuclear disarmament.

The two Koreas are set to reinstate a joint military commission, push forward with family reunions and even pursue a joint bid to co-host the 2032 Olympic.

With the release of Siti — and perhaps Doan — and no new suspects in the case, Kim Jong-un may have pulled off his most audacious crime.

-

Hero’s welcome for ‘sister’ Siti Aisyah

Far from the gathering political storm in Malaysia over her surprise release this week, Siti Aisyah was given a hero’s welcome on her return to Indonesia.

As Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad held a press conference to quash accusations the decision to drop murder charges against her was influenced by intense lobbying from Jakarta, Indonesian President Joko Widodo held a palace reception for the former child bride late on Tuesday.

In the Javanese village she left at 14, banners thanked Joko “for the return of our sister Siti Aisyah”.

Dressed in black hijab and grey batik and flanked by her parents, Siti said little as she fought her way through a crowd to the home of Sindang Sari’s wealthiest man.

“Siti Aisyah and her family will stay here as long as they like,” said Muta’I, a former village chief and local legislative candidate in next month’s elections.

“She will be safer here and can have her privacy while she cools down after her traumatic ordeal.

“She has been in prison for two years and the last thing she wants is to be overwhelmed with media attention, especially when asked about what happened. She is traumatised and wants to forget what happened and move on.”

No one in Sindang Sari says she is guilty of murder, nor that she had been recruited while working at a massage parlour in Kuala Lumpur.

Siti’s Aunty Darmi said her niece was a shy girl who married and had a child too young, only to be forced to seek work further afield when her marriage ended.

“The family didn’t know she was in Malaysia,” she says. “They only knew she was in Batam (an Indonesian island close to Singapore) working in a clothing store.”

The last time Darmi saw her was a fortnight before Siti’s arrest. She told her aunt she had been holidaying in Malaysia when she was approached to work on a reality television prank show.

“She said the show will soon be aired in Indonesia and that I should watch when it does,” says Darmi.

“Two weeks later I did see her on television, but on the news when she was arrested for murder. I couldn’t believe it and thought this must be a mistake.

“My brother cried day and night. We all told him: ‘Just pray, let the government take care of this, they are working to save her’ — and, thank God, that’s what they did.”

Nivell Rayda, Amanda Hodge

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout