The Rolling Stones’ Satisfaction has its roots in a faulty amp

The sound of the Rolling Stones’ Satisfaction began with a faulty amplifier being used to record a Marty Robbins track.

Guitarist Grady Martin knew a good sound when he heard it, and he didn’t like this.

His equipment had malfunctioned just as he was to play on what would be another Marty Robbins’s hit, a song called Don’t Worry. What happened in the next three minutes and 13 seconds would change music, and there are many versions of the story.

But Gordon Stoker, a veteran session singer, was there and not long before he died two years ago, he recalled the scene.

Stoker led the Jordanaires, famous for backing Elvis Presley, with whom they had recently recorded It’s Now or Never.

“Yeah, we had to ooh and aah all the way through that (Don’t Worry),” Stoker recalled.

“Grady said there was a tube blown out in his amplifier. He wanted to get a different amp and Don Law (the Englishman producing that day) said, ‘I like the way it sounded, old boy.’ We were standing there and I know it was in his amp.”

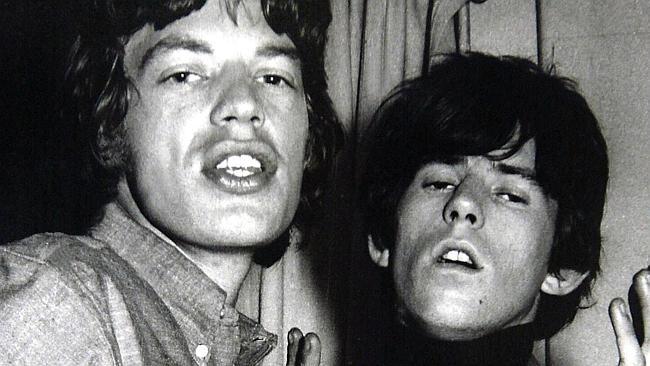

Don’t Worry charted strongly in the first months of 1961, Grady’s odd guitar sound catching the ear of English blues fan Keith Richards, who’d gone to school with Mick Jagger and had recently bumped into him at Dartford railway station. Jagger had some imported records under his arm; Richards was interested to see Jagger also inclined towards Chess label acts.

As the Rolling Stones, the band they soon formed, they would have an early hit with a song that copied Grady’s distorted six-string bass sound. Not only did it top US and British charts, it changed the terminology of popular music.

After (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction, bands no longer played rock ’n’ roll. It was just rock.

But the world almost missed it: unable to sleep in his room at the Fort Harrison Hotel in Florida (now owned by the Church of Scientology) on May 6, 1965, Richards picked up an acoustic guitar and worked on a simple riff based on the recent No 2 hit, Dancing in the Street by Martha and the Vandellas.

Taping these 10 notes on an early cassette recorder, Richards soon fell asleep. The next morning he found two minutes of the riff — and a half-hour of snoring. Later, by the pool, he and Jagger completed the lyrics.

On June 6, the Rolling Stones were in Chicago with a few days off to record at the legendary Chess studios. A few years before, Jagger had been posting money orders from his parents’ home in Kent to Leonard Chess to buy records.

The year before the Stones had released a quirky instrumental — 2120 South Michigan Avenue — the Chicago address of the Chess brothers’ building.

That day they ran through a simple version of Satisfaction, Richards telling his fellow musicians that the distorted guitar part would be played at a later date by a horn section that the band did not then have.

The band revisited the song at RCA’s Hollywood studios a couple of days later. The Stones’ producer and manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, found the propulsive, insistent opening riff addictive, and heard a hit, but to Richards it was still a work in progress.

“I never considered it the finished article,” he said later. A quick vote settled the issue: Satisfaction would be the next single.

It was the riff heard around the world — the most influential in rock music. Rolling Stone magazine rated Satisfaction the second greatest rock song of all time (after Bob Dylan’s Like a Rolling Stone). The song changed music like few others. If you wanted influence, you needed to conquer America. Satisfaction was the Stones’ first US No 1 hit and simple, thrusting riffs were soon to become the hallmark of rock.

With big-name artists — Otis Redding and Aretha Franklin among them — paying homage with their own versions, the British Invasion could be declared a victory: black American singers were copying songs written by Englishmen in the style of the American rhythm and blues they loved from afar.

The album on which Redding recorded Satisfaction — Otis Blue: Otis Redding Sings Soul — is considered his finest and Satisfaction, on which he is backed by Booker T and the MGs with Isaac Hayes on piano, its high point. That riff finally had its horns. It mattered not that Redding did it in such a hurry he couldn’t remember all the words and made many of them up on the spot. It was a show stopper at his concerts until his death two years later.

The machine invented to replicate Martin’s distorted guitar sound — the Gibson Maestro Fuzz-Tone — went from novelty to required equipment for anyone serious about rock.

The Stones classic was completed in the studio where Duke Ellington had, 24 years earlier, recorded the Billy Strayhorn classic that would become Ellington’s signature tune — Take the “A” Train. A recording of Ellington’s performance opened the Stones’ 1981 US shows and appears on their live album Still Life.

Ironically, it was Jagger (with David Bowie) who would take Dancing in the Street to the top of the charts, as part of the Live Aid phenomenon in 1985.

Satisfaction would change rock music, but not instantly. On August 7, 1965, after four weeks at No 1, it was replaced by Herman’s Hermits’ I’m Henry VIII, I Am.