State crashes into church in reply to ‘catastrophic failure’

Some churches are pushing back, but the royal commission’s recommendations on a response cannot be taken lightly.

It was a grim Social Services Minister Christian Porter who yesterday best captured the challenges facing governments and institutions after the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse delivered its report.

The report is compelling in its evidence and instinctively hard to oppose as it outlines a new national agenda for child protection.

But it is one thing for a commission of inquiry to report; quite another for a broad national consensus to be achieved that compels governments and institutions to act in unison.

Commenting on the most controversial recommendations in the report, including the issue of celibacy in the Catholic Church, Porter offered some cautious and practical advice.

“Now these are not necessarily matters inside the legislative control of the commonwealth government or, indeed, potentially state or federal governments,’’ he said. “So there are recommendations that need to be considered across Australia by the states, by the territories, by the commonwealth. And we should never lose sight of how important it is for each of the individual organisations and institutions, the churches and charities, to consider these recommendations.

“But it would be less than honest to pretend there is simplicity in the way in which responses will occur.’’

Porter might as well have been talking about the entire 17-volume report. For even as he spoke, state governments and institutions across Australia were contending with how to deliver on a $4 billion redress scheme that would be led, for all practical purposes, by the two biggest states.

Despite NSW and Victoria planning to sign up to a version of Porter’s scheme — which is a slightly watered-down incarnation of the commission’s vision — neither so far has inked a deal.

The reason for this is partly political and partly financial. Both state governments are looking for the best possible deal, just as many of the institutions are grappling with how they are going to fund compensation for abuse that occurred across many decades.

The same can be said of the commission’s headline — some might argue tabloid — attacks on basic Catholic Church practices. In a community that looks so relentlessly for simple answers, the commission yesterday coughed up some simplistic recommendations affecting the church, venturing into areas where the state rarely, if ever, bothers to tread: first, for the church to consider voluntary celibacy for clergy; and second, for it to consider breaking the seal of the confessional.

While Porter spoke in Perth, the archbishops of Sydney and Melbourne spoke in their respective states, gently suggesting that neither is likely to be amenable to overturning the most basic of church laws.

In Sydney, Archbishop Anthony Fisher made the clear — and perhaps obvious — point that overturning church law on the confessional was pointless.

“Killing off confession is not going to do anything,’’ he said. “Any proposal to stop the practice of confession in Australia would be a real hurt to all Catholics and Orthodox Christians.”

On celibacy, he added: “I think the debates about celibacy will go on, however people respond to this issue. We know very well that institutions who have celibate clergy and institutions that don’t have celibate clergy both face this problem … it is an issue for everyone, celibate or not.”

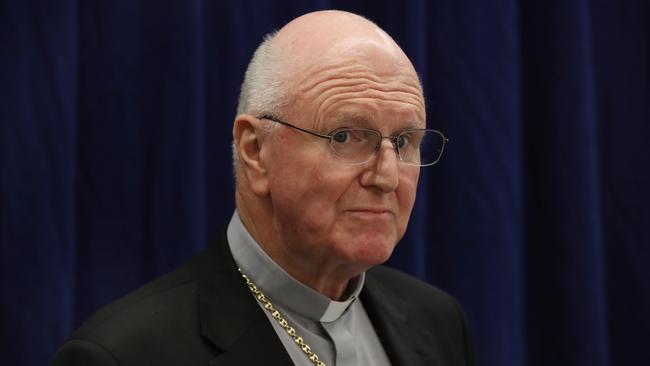

Meanwhile, down the Hume Highway, Archbishop of Melbourne Denis Hart was equally dismissive of the likelihood of substantial reforms to basic Catholic institutions and traditions.

“My sacred charge is to respect the seal of the confessional,” he said.

However, he made it clear that the commission had served a significant purpose, something that no one with any credibility was denying yesterday.

“It can’t be true we have done nothing,’’ Hart said. “(But) I’m grateful to the royal commission because I don’t think we could have done it in the forensic, objective way right across the community that this terrible evil demands.’’

It is a natural inclination of anyone who drowns in years of stories of abuse to demand a system of fairness for those who have been offended against, to demand that a line be drawn in the sand between what happened yesterday and what will happen on the sexual abuse front into the future.

It’s a future where abuse is most likely to occur in the family home, in residential care for the young homeless and, proportionately, in some indigenous communities.

“Now that the royal commission has completed its work, it is the responsibility of governments and institutions to consider and respond to our conclusions and recommendations,’’ the commissioners implored yesterday.

The weight of the commission report, to that end, may well lie in the formation of a national child-safety protection network that will hopefully change the way all Australians function: that is, a system of checks and balances that requires people to respond on a daily basis to a series of accountability measures and minimum standards that put children first.

The commission’s second legacy will be the vast number of cases that surfaced during its inquiries.

At the end of July, the commission had referred 2252 cases of alleged child sex abuse to the police.

Evidence was heard of tens of thousands of sex-abuse victims in thousands of institutions; offending also is vastly under-reported, and sometimes reporting occurs decades after the offence.

The Catholic and Anglican faiths had dominated complaints against the churches: 4756 against Catholic offenders, mostly between 1950 and 1989; and 1119 reported Anglican complaints, between 1980 and 2015.

Entities such as the Salvation Army and Jehovah’s Witnesses were reported to be widely represented in abuse settings.

The commission also has made significant recommendations on the Anglican Church, demanding a national approach to the selection, screening and training of candidates for ordination.

It calls for a uniform episcopal standards framework that ensures bishops and former bishops are accountable for their responses to complaints of child sex abuse.

Yesterday the head of the Anglican Church of Australia, Melbourne Archbishop Philip Freier, expressed regret at the level of offending in the church.

“Case studies involving branches of the Anglican Church have been shocking and distressing for Anglicans, and have confronted us with our failings,’’ he said. “The Anglican Church has worked assiduously since 2004 to make the church a safe place for all — especially for children — and we have made great strides, often in response to recommendations from the royal commission.

“But we admit that sometimes we have been slow to grasp the extent or severity of abuse, and that without the work of the royal commission we would not have been able to achieve this.

“There has been a change in the wider culture of the Anglican Church about child abuse as all elements of the church have had to face our failures — a change that, again, was largely due to the royal commission and the church’s response.”

At the heart of the commission’s 189 recommendations is a requirement that all levels of government respond in accordance with the directions of a newly appointed federal minister charged with dealing with child sex abuse.

Such a minister may or may not be appointed.

The Council of Australian Governments also has been called into action, with the commission effectively demanding that it monitor progress and set the agenda for reform, which would include a new national framework for child safety by 2020.

These layers of accountability are designed to prevent administrations from avoiding their responsibilities or failing to act when the heat of the debate dissipates.

It has been widely reported that institutions failed dismally in their responsibilities to children, in many cases by refusing to report crimes.

Horrific examples of non-reporting were detailed over several years and the commission is proposing that failure to report should for the first time be made into a criminal offence, with the law affecting clergy who fail to report admissions made in the confessional.

But the report also calls for national mandatory reporting laws for out-of-home care workers, youth justice workers, early childhood workers, registered psychologists and school counsellors, and people in religious ministries.

It also calls for all levels of government to introduce specific protections for anyone who reports child sex abuse in institutions, recommending they be protected from civil and criminal liability and from reprisals or other detrimental action as a result of making a complaint or report.

In another significant shot at church leaders, the report backs NSW-style laws that require heads of institutions to notify an oversight body of any reportable allegation, conduct or conviction involving any of the institution’s staff.

Further, it wants government and the institutions to be held accountable to 10 so-called child safe standards designed to improve accountability and educate the country on the minimum requirements when dealing with children.

These include embedding child safety in institutional leadership, governance and culture, and ensuring people working with children are suitable and properly supported.

Although these standards are likely to be dismissed by some as motherhood statements, they are part of a broader agenda by the commission to ensure that the mistakes of the past are not repeated.

For many victims, the commission gave voice to a subject that was cloaked in secrecy and shame.

Manny Waks, a Yeshivah abuse survivor and whistleblower, believes the commission has been an epiphany.

“From my perspective the Jewish community has had a monumental shift in the way issues of child abuse are addressed,’’ he tells Inquirer.

“People are now talking about child sexual abuse in a forthright and open manner. Prior to the royal commission, it wasn’t talked about openly, if at all.

“Reports and findings and revelations that we saw coming out of the royal commission really did change attitudes in the community,” he adds.

This is what the commissioners were looking for.

All it needs now is the political and institutional willpower to deliver on the recommendations.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout