Position vacant: human

Robotics threaten the workplace globally, but one academic says the future of work will focus on the tasks robots can’t do.

The literature on the future of work can be gloomy, if not dystopian. The genre works on fear plus just enough hope that if we are somehow smart enough we will be among the minority able to hold on to jobs in the decades ahead.

Richard Baldwin’s new book, The Globotics Upheaval: Globalisation, Robotics and the Future of Work (Hachette), published today, doesn’t avoid the tough calls about the impact on our economies of offshore workers and automation.

But the American-born Swiss academic is more optimistic than many commentators. Indeed he suggests life could actually be better in the future — as long as we understand that the edge we have over the machines is our humanity. On the phone from Geneva where he is professor of international economics at the Graduate Institute, Baldwin suggests we need to spend less time worrying about what artificial intelligence and remote workers overseas workers can do more cheaply than us and focus on where we have the upper hand.

Says Baldwin: “I think human ingenuity is infinite and we will eventually find new jobs for everybody. Our task is to figure out what those jobs will be doing and the way to do that is to figure out what globotics can’t do.”

Globotics is Baldwin’s generic word for the phenomenon of white-collar robots that will work for nothing and the new phase of globalisation led by tele-migrants who will work remotely for next to nothing. These workers will not be stopped by Mexican walls or border security but will happily and legally work for very low wages from their own countries.

None of this is especially new but Baldwin says the convergence of artificial intelligence and machine learning with cheap, remote white-collar workers is escalating at levels we cannot assimilate easily into our “straight-line” approach to progress.

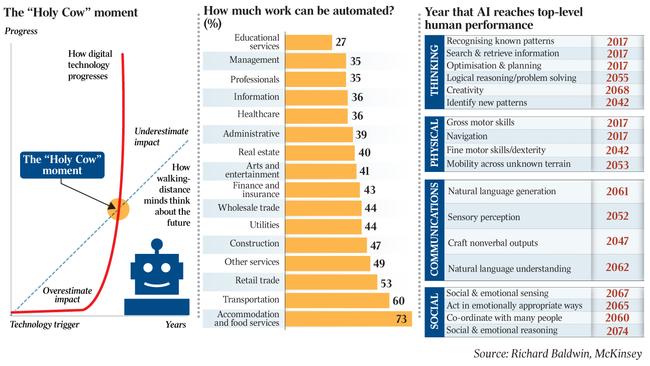

Computer processing speeds double every 18 months, he writes. So, the increment in power between 2015 and 2017 was twice as large as all the progress in the previous 46 years. Draw this as a graph and we see that when the explosive growth of digital progress crosses our straight-line approach to the future, we experience a “holy cow” moment. The point is that we are still shocked by how fast work is changing in the 21st century.

The bad news is the potential for a backlash from disaffected blue and white-collar workers who together could cause even bigger headaches for our politicians than displaced manufacturing workers already have in places such as the US. The good news, says Baldwin, is that the upheaval could reduce rather than increase the gaps between workers — nurses armed with AI for diagnosis will win out compared with doctors, for example. The trick, says Baldwin, is to think about what the globots are not very good at — “the human skills like managing people, empathy, creativity, ethics, integrating with large groups of people, sympathising with people”.

Baldwin says the literature often conflates job losses from manufacturing with those in services, even though only 10 per cent of the workforce is in factories.

“It’s a big, big mistake,” he says. “It’s a little bit rough, but who cares?” Industrial robots are certainly taking jobs but it’s the “software robots living in computers” that preoccupy Baldwin. “These automated things will take any kind of routine, data processing or rules-based elements out of our jobs,” he says. “The new jobs of the future for humans will emphasise the things the (robots) cannot do.”

This much we know, but the extra element in the coming revolution, according to Baldwin, is that machine language will erode human-based jobs even further. The capacity for machines to translate quickly increases hugely the job options for people living outside the West.

“Chinese universities alone graduate eight million students a year, and many of them are underemployed and underpaid in China,” Baldwin writes. “Now that they can all speak ‘good enough English’ via Google Translate and similar software, special people in rich nations will suddenly find themselves less special. This international tidal wave of talent is coming straight for the good, stable jobs that have been the foundation of middle-class prosperity in the US and Europe and other high wage economies.”

What will be left will be jobs that absolutely need face-to-face interactions — jobs that are more human and necessarily more local, according to Baldwin. Here’s where the hopeful bit comes in and why we should not make the mistake that this digital revolution will mimic the industrial and information technology revolutions of the past 300 years.

Says Baldwin: “The shift from farms to factories went from about 1720 to 1970 and was driven by technology that was especially good for people who work with their hands, and indirectly good for people who work with their heads. It was very good for equality … it sort of evened things out. From 1973 till 2016, when I think this (digital revolution) really got started, there was a technology (ICT) that was a better substitute for people who worked with their hands, but also better tools for people who worked with their heads. As a consequence there was a radical increase in market inequality everywhere and certainly in all the advanced economies.”

Some economies evened out the disparities with social welfare policies but overall the past half-century has helped people who were already ahead of the pack and hurt those who were behind.

“Most people assume that digital technology will be just more of the same, but I think that is probably mis-thinking the whole thing,” Baldwin says.

Our economies reward those — the doctors, lawyers, draftsmen, architects, tax accountants — who can mix human skills with experience in pattern recognition. But technology can use data sets to provide levels of pattern recognition that until now have been the preserve of highly paid, experienced workers.

“What this (revolution) does is give more head to people who have heart but not more heart to people who have head,” says Baldwin. “Artificial intelligence can sometimes be viewed as augmented intelligence and the people whose intelligence it is augmenting the most are the middle mental skill kind of people. There will always be the AI geniuses who become billionaires (but) the question is whether this is going to help the doctor more or the nurse.”

The answer, of course, is that nurses will have most to gain because so much more diagnosis will be provided by data sets. Baldwin says he’s hopeful that globotics will be a “boost to the middle class and not just the upper class”.

None of this transformation will be smooth. The backlash will likely focus — as it has done recently — on big tech companies.

“I suspect this is going to be a big issue in the 2020 US presidential election and some other ones,” Baldwin says, with governments arguing they can help people adjust to change. “It’s about not (seeing) technology as being against workers but, rather, for workers.”

That, of course, is a long way from the populist approach taken by Donald Trump in the 2016 election. “Trump was riding on the discontent of people who were hit by the last adjustment, the information and computer technology revolution that led to offshoring and automation of jobs,” says Baldwin.

“They gave the Democrats eight years under Obama, they gave the Republicans eight years under Bush. Nothing changed, so why not give this guy a try? But they got nothing out of it. Brexit, Trump, Le Pen, the Five Star Movement (in Italy) — none of them have solutions. It’s like treating brain cancer with aspirin. It just makes them feel better. So I think they are going to be ripe to join people displaced by digital technology. There is this powder keg of discontent that came from the disruption from robots and China in the manufacturing sector and now we’re going to add on the white-collar workers.”

It’s not easy to predict which jobs will be sheltered from the storms but Baldwin draws on material from McKinsey and other researchers to suggest, for example, that 73 per cent of work in the accommodation and food sector could be lost to robots. Jobs that involve judgment, emotional intelligence and dealing with unexpected situations — such as education and healthcare — will lose far fewer: about 27 per cent to 36 per cent of jobs respectively.

Baldwin is optimistic that our “human edge” will provide shelter from the globots for a long time. Again he quotes McKinsey researchers to argue that it will take about 50 years for AI to attain top-level human performance in the four social skills so useful in the workplace: social and emotional reasoning; co-ordination with many different people; acting in emotionally appropriate ways; and social and emotional sensing.

Just as machines have limits, so do the tele-migrants because there are some workplace tasks that need “real people to be in the same room at the same time”. Which is why Baldwin likes to talk about the potential for a “more local, more human, community-based economy”.

He claims three things point to this:

● The jobs that will be left after the robots and tele-migrants take their slice of the work will require face-to-face interaction, making communities more local and probably more urban.

● The jobs that will thrive after the “globotics upheaval” will stress humanity’s great advantages such as creativity and innovativeness.

● Once we manage the transition the globots will make us richer: cheaper goods mean we will be materially better off, for example.

“The globotics revolution could mean soaring productivity that could finance a breakthrough to a new nirvana, a better society that offered fulfilling work and fostered more caring and sharing attitudes,” Baldwin writes.

He concedes that in the short term it is hard to know how long that transition will take, something that is cold comfort for those rendered jobless. Even now, early in the revolution or transformation, as Baldwin calls it, citizens can feel powerless. Meanwhile, he argues governments must help workers adjust, foster job replacement, “and if the pace turns out to be too great — slow it down”.

He argues we need more adjustment policies such as retraining programs, and income and relocation support, which have worked in Europe. Governments also must find a way to make rapid job displacement politically acceptable to most voters.

“Politics is a fine art involving inspiration and leadership as well as concrete policies,” Baldwin writes. “But whatever they use, our political leaders will have to find ways of sharing the gains and pains, or at least offering a perception that everyone has a fighting chance of being a winner.

“While tax-and-redistribute policies undoubtedly have to be part of this package, they cannot be the only thing, or even the main thing. People’s lives are too tied up with their jobs to allow it. The challenge is ensuring that labour flexibility doesn’t mean economic insecurity for workers. What is needed are policies like those in Denmark. The government allows firms to hire and fire freely but then commits to doing whatever it takes to help the displaced workers find new jobs.”

Baldwin says we will also see a move to “shelterism”, where interest groups — such as taxi drivers — will try to use existing regulations to slow change. He cites privacy, health and safety and security regulations as examples of this “micro” pushback. At the macro level employment protection legislation around firing people could be used to slow automation.

And when employees can often feel bewildered in the face of big tech and an uncertain job outlook, Baldwin suggests we could all turn ourselves into “data workers” and operate in a new economic model. He cites the work of two Chicago writers, Eric A. Posner and E. Glen Weyl in their book Radical Markets, published by Princeton University Press last year. The idea is that we treat the data that tech firms are already so blithely collecting from us as we would our labour and charge the firms for the use of it.

“So, at present we have a model where data is capital,” he says. “I agree to use an iPhone and then I agree to let them use my voice data to train Siri. My data is capital as far as Apple is concerned. They get to do whatever they want. They’ve bought it. It’s theirs. So the Radical Markets guys say, no let’s treat it as labour, where you have to pay me copyright. That would change the economic relationship around completely.” Above all, Baldwin says the pace of progress is not set by “some abstract law of nature”.

We can control the speed of disruption: it’s our choice.

The Globotics Upheaval: Globalisation, Robotics and the Future of Work by Richard Baldwin is published by Hachette Australia ($32.99).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout