Parra Trooper, Di-Bak blocked as chemical herbicides fail

Biological products effective in curbing weeds are being blocked even as chemical herbicides face resistance.

Australia’s farmers spend more than $1.5 billion a year on chemical herbicides to kill weeds. Herbicides rarely destroy seeds and their repeated use has given Australia the world’s worst herbicide resistance problem, with many products now ineffective, according to the CSIRO.

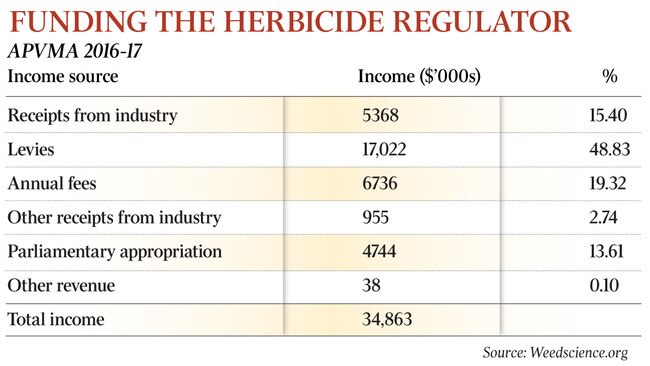

Despite this, the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority has blocked and delayed the sale of non-toxic biological controls for some of Australia’s worst weeds.

The APVMA’s product registration system is tailored to chemicals and its staff lack experience in assessing biological alternatives, critics say.

In 2012, University of Queensland scientists unveiled “Australia’s first homegrown commercial bioherbicide” to kill the introduced parkinsonia prickle bush, which has spread across northern Australia. Branded as Di-Bak, the bioherbicide contains native fungi that selectively destroy parkinsonia and its seeds.

BioHerbicides Australia, a company part-owned by UQ, applied for APVMA registration of Di-Bak in 2012, after eight years of trials at 150-plus locations. The product has reached final approval stage only now, despite legislated timeframes that require the APVMA to finalise the most complex applications within 18 to 25 months.

“We assumed the process would be relatively straightforward, given that our product is basically composed of native fungi,” BHA’s managing director Peter Riikonen says.

“However, the APVMA’s mindset and systems are very much chemical-oriented and they had never dealt with a biological weedkiller before ours. I have sat across the table from the APVMA many times. They have very little functional knowledge of soil biology and the behaviour of native fungi, and have been reluctant to make a decision to approve this innovative product.”

Riikonen says BHA spent more than $500,000 on the application and the delay had cost it more than $1 million a year in lost sales.

“Every time we responded to a request for additional information and data, they referred our response to appointed experts, which often resulted in requests for additional studies or evidence in a circular process which gained little forward traction,” he says.

“There is a great unmet demand for non-chemical solutions from farmers, Landcare groups, councils and national parks. Our bioherbicide is environmentally safe and a lot cheaper in the long run because you don’t have to apply repeat treatments, as you do with chemicals. It is ridiculous that a biological agent should have to be registered as a chemical product through the APVMA.”

A spokesperson for the APVMA — which was moved from Canberra to Armidale in the NSW northern tablelands at the behest of local member Barnaby Joyce — says the BHA application is “complex” and requires “multiple efficacy and environmental assessments”.

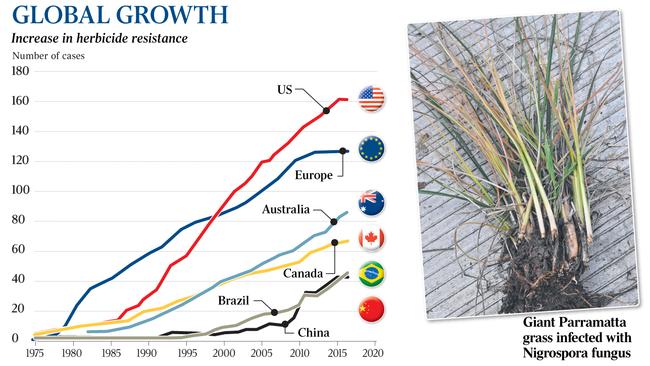

Resistance to chemical herbicides is on the rise. There are 255 species of herbicide-resistant weeds globally, according to the collaborative International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds.

Its website says weeds have become resistant to 23 of the 26 known herbicide sites of action and to 163 herbicides. Herbicide-resistant weeds have been reported in 92 crops in 70 countries. Meanwhile, the APVMA has ordered cattle farmer Jeremy Bradley to stop advertising and selling a native fungus that kills giant Parramatta grass, an introduced weed that has degraded east coast pasture.

Yet the NSW Department of Primary Industries advocates use of the same fungus Bradley sold from his Hastings Valley property on the state’s mid-north coast.

For decades, farmers have struggled to rid their paddocks of GPG by using herbicides such as glyphosate, the active ingredient in the popular but increasingly contentious weedkiller Roundup.

Several years ago, DPI researchers led by agronomist David Officer discovered that the fungus Nigrospora oryzae caused lethal crown rot in GPG. Officer advised farmers to dig up diseased plants and relocate them to spread nigrospora, and councils started to transplant infected plants along roadways. Bradley, who has won two Australian government Landcare awards for his innovative use of fungi to improve soil health, set out to develop a concentrated source of nigrospora that could be mixed with water and sprayed on paddocks.

He and his wife, Cathy Eggert, experimented for four years and invested their life savings of $150,000 before succeeding in breeding the fungus, which they sold in bags under the Parra Trooper label.

Last year the APVMA told Bradley he could not sell Parra Trooper unless it was registered as a chemical product. The authority said that under the Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals Code, the definition of a chemical product “includes the effect of modifying the physiology of a pest plant so as to inhibit its natural development, for example by initiating/promoting crown rot in giant Parramatta grass”.

Bradley says he cannot afford expensive APVMA product tests designed for chemicals rather than biological agents.

“It is absurd that a native organism naturally present in our paddocks is treated the same as a synthetic toxic chemical. We have not modified nigrospora in any way; we simply provide it in a more effective and easier-to-use form. Yet we are banned from selling it while the DPI and councils spread the same organism around in clumps of grass and soil.”

The APVMA tells The Australian “substances extracted from plants and used as pesticides (plant extracts) require APVMA registration” but “plants used as biological control agents” do not.

Officer says he has studied nigrospora’s impact on GPG and related weeds for 20 years and has seen no evidence of damage to other species.

“It’s not up to me to comment on what is or isn’t a chemical, but my personal view is that we have done due diligence and I don’t believe there is a significant risk from moving the fungus around,” he says.

Almost 400 farmers have provided written endorsements of Parra Trooper on a petition to amend the regulatory Agvet Code to exempt Nigrospora oryzae from regulation. Virginia Jung, a cattle farmer near Wauchope in northern NSW, says she signed the petition because Parra Trooper was more effective and cheaper than the non-selective chemical glyphosate, which killed all vegetation and resulted in worse GPG infestations the following year.

Bradley’s federal MP, the Nationals’ member for Lyne, David Gillespie, says he has used Parra Trooper to kill GPG on his own cattle property and made unsuccessful representations to the APVMA on Bradley’s behalf.

“The APVMA said that because he (Bradley) has put a label on it and put claims about the product on the packet, then under the regulations it is treated as a chemical,” Gillespie says. “I said to them (APVMA), it’s a technical fine point, for goodness sake, get real. I respect your authority but it’s an endemic fungus which Bradley is expanding the spread of to control a problem weed.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout