Online privacy has flown out the window

Not even new laws can put the genie back in the bottle.

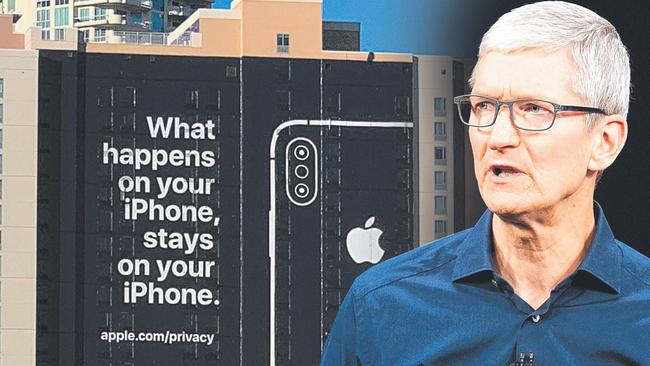

Apple didn’t attend CES, the biggest consumer technology festival, this year, but it did have a presence. It paid for a huge billboard near the event in Las Vegas last month, one that attendees found hard to miss, given it covered about 13 floors of a building.

“What happens on your iPhone stays on your iPhone,” the ad read, along with a link to Apple’s privacy website.

Google and Amazon, despite controversies surrounding both companies, had a strong presence at CES and unveiled a host of new products related to Google Assistant and Amazon Alexa.

However, Apple — which tends to stay away from CES — tried to rise above its peers both literally and in the context of the privacy rows plaguing them.

MORE: The People v. Tech

The subtext was clear: the likes of Facebook, Google and Amazon use and sell your data, while Apple is squeaky clean and can be trusted to protect your most intimate information.

Apple boss Tim Cook has the luxury of posing as a champion of privacy because his company, the first in the world to attain a trillion-dollar valuation, makes its money by selling expensive smartphones rather than flogging intrusive advertising.

There’s also a portfolio of subscription services, including iTunes and Apple Music, which bring in a steady stream of income without Apple having to sell customer data to third parties.

Cook’s posturing isn’t without risk, however; Apple has had to deal with privacy bungles of its own.

It’s all very well for Apple to claim “what happens on your iPhone stays on your iPhone”. But just ask the 500 celebrities, mostly women, who had intimate photographs stolen and leaked online in a massive iCloud scandal in 2014.

Apple said the leak was a result of phished user names and passwords, and was not a “hack” as such. But the result was the same. Photos and other intimate data kept in Apple’s iCloud are not untouchable, and in the case of these celebrities the photos taken with their iPhones became public for the world to see.

Third-party apps and data held by other companies on Apple’s iPhone are also not immune to misuse.

Apple’s billboard was splashed across a Marriott hotel, which is somewhat ironic considering months earlier Mariott announced that five million passport numbers were stolen from it as part of a mass data breach. That was from bookings made on iPhone and Android devices.

The iPhone maker is also still dealing with the fallout from the serious bug in group FaceTime that allowed callers to spy on those they were calling. The bug turned the iPhones into microphones, leaving those receiving the calls open to surveillance even if they didn’t answer the call.

Apple has now fixed the issue but the company hasn’t escaped regulatory scrutiny, especially in relation to how long it took to warn consumers.

The fact that the bug was released to the public in the first place is an embarrassment for Apple, belying the security mantra being publicly pushed by Cook.

Daniel Lai, head of Canberra-based cybersecurity software developer ArchTIS, says the escalating war between Apple and Facebook over privacy practices, and revelations in Google’s annual report last week that its business is being crippled by changing data privacy practices, all point to one truth.

“Legislation is catching up to all of us, particularly when it concerns trusted information sharing and the security of consumer data,” Lai says.

“In this new paradigm of trust, recognising the importance of securing and protecting consumer data must be paramount to how all institutions operate from the outset.

“Quite simply, technology giants like Apple and Facebook have killed the goose that laid the golden eggs.

“If they had treated consumers with dignity and respect, engaged them and let them know exactly how they would be using their individual data from the beginning, they wouldn’t be in this situation right now.

“At the Gartner Symposium this year, for the first time in their history respondents to their annual surveys placed security and privacy above convenience.

“Apple has obviously caught on to this and is now trying to use this as a differentiator.’’

According to Lai, a wave of cyber security and privacy legislation is about to hit, led by the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, and some of it involves the possibility of criminal sanctions.

“This is going to play havoc with these companies’ bottom line and reputation across the globe,” he says.

“The cost of becoming compliant with these legislative requirements is estimated at $US7.2 billion ($10.1bn). We are entering into a new age where global companies need to reassess their relationship with consumers and citizens’ information.

“The free lunch is over.”

As regulation forces the technology companies to take customer privacy seriously, legal measures to rein in the digital behemoths may be too little, too late.

Scott McKinnel, managing director of internet security specialist Check Point, says consumers need to rethink their expectations about privacy on the internet.

“If you are on a digital platform, the concept of privacy no longer exists. It’s pretty much gone.

“The idea that you can be private on the internet just isn’t possible. What you need to do instead is limit the amount of personal data that’s out there.”

Tom Sulston, board member at the Australian NGO Digital Rights Watch, says customers have every right to demand privacy but technology companies are not necessarily willing to deliver that.

“As a consumer you have to be a bit cynical, a bit cautious and think about what data you are putting into the system, why a company is asking for this data and what they are going to do with it,” he says.

Sulston is optimistic that regulation can play a role in keeping tech companies honest and says Australia may follow the likes of Europe in passing commonsense laws.

“The tide is slowly turning, with the GDPR in Europe clearly stating that companies can hold the data and use it only for a specific purpose.

“It’s a great piece of legislation and is broadly good for all of us. It’s becoming the de facto standard as other countries take a look at it.

Consumers have until now had very little control of their data, very little protection but governments are saying that’s not acceptable.”

McKinnel and Sulston are particularly wary of social media networks, which are built to hoover up as much personal information as possible.

According to McKinnel, there’s no way of turning back the clock on the likes of Facebook and Twitter other than consumers cutting the cord completely.

“We can’t put the social media genie back into the bottle, even with legislation,” he says.

“People do things online that they won’t do in the real world. There are no social norms, there’s no code of conduct.”

Sulston says the lack of informed consent is a serious problem on social networking platforms.

“When I go to Facebook on my web browser, it also knows every other website I have been on, and that’s not an informed act of consent and a lot of technology companies struggle with this,” he says.

“They give you these terms and conditions, which is a massive document with a clause that says they can do whatever they want with your data. That’s not OK.

“We are seeing greater aggregation of social media platforms under the control of the one company: Facebook owns Instagram, WhatsApp and a host of other properties, so the ecosystem isn’t healthy and we have to be very strict about the expectations we, as a society, have on what these companies can do with our data.”

Although platforms such as Google and Facebook may eventually be obliged to bend their knees before regulators, a hyper-connected world replete with sensors and voice assistants like Amazon’s Echo could further complicate the privacy equation.

“The internet of things poses a similar challenge to those posed by the digital platforms. There are clear benefits on offer but what we need is an informed process to work out whether you want a listening device put in your home,” Sulston says.

But informed consent relies on transparency, which has usually received little attention from the technology companies, given the technical complexities involved in making the necessary devices.

No global standards exist to govern digital platforms or emerging trends such as the internet of things.

Sulston says: “When it comes to digital platforms, we are kind of where cars were in the 1970s.

“We have been building computer systems for some time, and while we are getting mass uptake now, we haven’t solved the problems around regulations and technical implementations.

“Digital by its very nature is very quick to market. You can move very quickly, but the problem with that is that you don’t have to jump through any rigorous regulatory or engineering hoops like you would if you were building a new car or an aeroplane.”

The rush to build things quickly means flaws fly under the radar and the social impact of the technology is underestimated.

It also creates an environment where consumers unwittingly leave themselves vulnerable to exploitation.

McKinnel says the idea of consensual data collection and management has been an afterthought in the digital environment.

“These concepts just didn’t figure in the early stages of the digital revolution and, while regulators are clamping down, the genie is out of the bottle.

“There are honest brokers out there but there’s no clarity yet on what they use that data for.”

The best protection for consumers, McKinnel says, is to limit the data they share and to understand how valuable that data is.

“The most important thing to do is minimise the fallout,’’ he says.

“Privacy principles are inevitably going to be tightened up, but the first thing we need to do is data classification, building clear guidelines on what data is sensitive and what isn’t.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout