NT on a steady trajectory towards fiscal disaster

The NT is on a steady trajectory towards fiscal catastrophe.

They say good governments make opportunities out of crises, while bad ones do the opposite. The Gunner government’s latest bombshell financial report makes clear that the Northern Territory has had a run of bad governments lately.

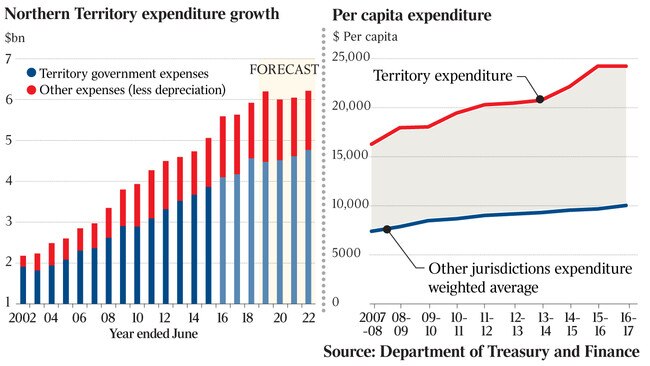

“Over the past 20 years, the Territory has incurred fiscal deficits not only during contractions in the economic cycle but also in times of expansion,” is the report’s opening line.

“The deterioration in the Territory’s operating balance from 2016-17, following reduced GST revenues, has placed the Territory in the unsustainable position of needing to borrow to pay for recurrent activities, including interest expenses.”

The notionally independent report, entitled A Plan for Budget Repair, was prepared by NT public service head Jodie Ryan (a former under-treasurer), current under-treasurer Craig Graham (Ryan’s former deputy) and two “independent reviewers”.

It spectacularly confirms what experts have been saying for years (often to loud denials from those in power): that the NT is a mendicant state living handout-to-handout and without a viable plan to manage its finances or become sustainable in the future. It is, in effect, a bureaucratic manifestation of the sorts of problems it was created to solve.

“The Territory cannot grow its way out of the current fiscal predicament in the time required,” the report says.

“In the absence of immediate and sustained expenditure restraint, the next generation of Territorians will bear a growing burden of current expenditure through interest costs and reduced capacity for service delivery with interest expenses approaching $2 billion per annum, or around 12 per cent of total expenditure.

“This also means that a substantial proportion of borrowing over this period would be used to pay interest costs rather than deliver the services that future Territorians will need.”

Let’s not forget that only last month, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe travelled to Darwin to declare open the $54 billion Ichthys liquefied natural gas project, Japan’s largest overseas investment and a historic opportunity for the Top End. The report says the Territory now faces a future with net debt levels above 320 per cent unless someone intervenes.

How did it go from double-digit economic growth to a fiscal crisis so abruptly? To understand that, you have to know a bit of history.

Early in self-government (which began in 1978), the Territory operated under a federal funding regime that rewarded adventurous development.

The Country Liberals, who ruled uninterrupted until 2001, built things partly because Canberra paid them to do it. When Labor took power in 2001, it sought to modernise what had become seen as a “silver circle”. Labor’s rise also coincided with the advent of the GST system.

Through the early 2000s, Clare Martin’s government maintained a semblance of fiscal harmony while receiving more GST revenue every year. It also secured the Darwin LNG development and the Ichthys project.

Darwin’s legacy as a public service hub and population centre taught all parties to suck up to the public sector. A popular refrain among business types whenever times look tough is that “the government just needs to spend more”. The Territory government thus “has tentacles everywhere … (and) is such a centrepiece of the economy”, as former NT treasurer and federal MP David Tollner once opined.

Trouble began just as John Howard was approaching the end of his reign as prime minister. The Howard government launched the NT Emergency Response to a child protection crisis of the Martin government’s making. Paul Henderson replaced her under cover of Kevin Rudd’s federal victory and then nearly lost power himself through a snap election.

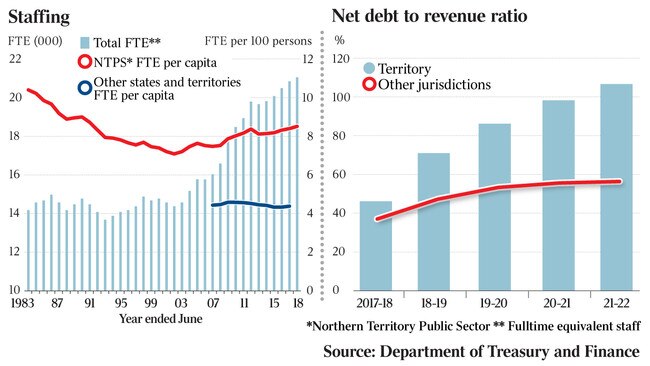

In the medley that followed, Labor spent big to calm public anger and avoid a recession during the GFC. The public service and public debt ballooned as Henderson and his colleagues sought to keep people employed by inventing bureaucratic positions and reasons for public tenders. Crusading Darwin accountant and then NT Council of Social Service president Barry Hansen helped reveal evidence that revenue intended to tackle disadvantage was being misspent pork-barrelling urban electorates. Labor was roundly criticised for its management of Strategic Indigenous Housing and Infrastructure program, which delivered a “net deficit” of bedrooms.

The Country Liberals regained power in 2012. Terry Mills and his colleagues won with four extra bush seats (but no urban ones) in a poll where Aboriginal electors showed for the first time that they could determine who forms government.

During the 2012 campaign, John Elferink (who went on to become attorney-general but was then hoping to be treasurer) was a feature at intersections beside a board depicting rising net debt. Elferink used to preach about deficit disasters and now says the NT has gone “beyond the brink of survival”.

“The solution, according to the NT government, is an act of unbridled charity on the part of the commonwealth in the form of a bailout,” Elferink says.

“That won’t happen. The commonwealth will demand austerity as Europe demanded it of Greece … because the NT is so dependent on government spending, the cuts that will be required will push the NT into a recession that will last at least a decade.

“House prices have already tanked, and getting rid of 10 per cent of the public service, which is what would be required, would ruin any residual value.

“Upping taxes to cover the shortfall would place so much pressure on residents that they would simply leave, compounding the problem.”

The now Country Liberal opposition blamed Labor. Deputy opposition leader Lia Finocchiaro says the Gunner government’s fracking moratorium restrained private sector spending just as Ichthys-related work was winding down.

“At the same time it has boasted record spends, increased taxes and wasted extraordinary amounts of money on policy changes,” Finocchiaro says.

“It has borrowed more than we can afford and has no plan on how to pay this money back.”

To be fair to Labor, the Country Liberals government (of which Finocchiaro and opposition leader Gary Higgins were part) did not distinguish itself while in office.

Mills’s factional opponents used modest austerity measures agreed by cabinet early in his term to foment an urban-voter backlash so severe that his colleagues lost their nerve and booted him from the leadership after just seven months.

Mills’s replacement, Adam Giles, then bungled a series of sensible-seeming asset sales so badly that he and his colleagues became enemies of the people. That combined with further internal warfare saw the Country Liberals ousted in 2016 in their worst defeat, going from 16 members to two.

Through its own chaotic period, the Giles government also spent wildly in an apparent attempt to retain power.

“Own source government revenues were significantly boosted in 2014-15 and 2015-16 through asset sales,” the budget repair report states.

“These one-off revenues were predominantly used to fund a range of infrastructure stimulus and investment initiatives during a relatively strong period of economic growth.”

The report overlooked GST windfalls the Giles government received, perhaps because blaming “GST cuts” is Gunner government Treasurer Nicole Manison’s schtick. Manison says GST reductions were not forecast in Treasury’s pre-election fiscal report.

The CLP’s first treasurer, Robyn Lambley, says she was “told very clearly that there would be a reduction in GST payments in the coming years”.

After peaking at 15 times Western Australia’s return on the dollar, it was hard to imagine the NT’s share would not drop.

Nevertheless, the outgoing Giles government upped total outlays by more than 12 per cent year-on-year in its final budget, even in the face of declining revenue. As Charles Darwin University professor of public policy Rolf Gerritsen told this newspaper in May 2016, shortly before the August election: “We’ve sold the jewels, and we’re about to spend what’s left over. Whoever wins the next election is going to have no money. This is like the last laugh before NT politics gets serious.”

That prediction turned out to be right.

Then opposition leader Michael Gunner promised on election eve to “make the hard decisions necessary to maintain the path to surplus” within a term. His government ditched that promise within 12 months. Because the Country Liberals lost power after a term studded with pantomime-like mishaps, Labor returned to office before it was ready. A chaotic government that drowned out its own arguments with infighting has been replaced by an immature one that seems unable to get its point across.

Behind all this, the Territory’s political economy remains unchanged: two decades of rising economic tides — courtesy of GST payments, major projects and federal grants — have spoiled the major towns to the point where their voters expect to be bought.

Meanwhile, persuasive academic and other studies argue remote incomes are falling and living conditions have barely improved in the bush.

Painfully little of the roughly $70,000 per person annually that the Productivity Commission estimates governments allocate to servicing indigenous Territorians ends up in the pockets of indigenous people. Problems with land rights administration have created royalties streams that feed social dysfunction and frustrate development. Aboriginal people are, in the words of certain leaders, “land rich but dirt poor”. The need for someone to make an opportunity out of a crisis could not be much starker.

One long-term interested observer who asked not to be named looks on aghast. “This trainwreck is the result of almost incredible (financial) imprudence and management failures, and has been expected by most (if not all) informed observers,” he says.

“Those who fought for self-government in the past would be mightily ashamed that their vision has been so sullied … The Northern Territory of Australia (Trustee in Bankruptcy Appointed) doesn’t quite reflect the hubris of the past few years.”

Since the early 2000s, the NT’s public service has increased in size by almost half. Nearly 40 per cent of those bureaucrats are in administrative rather than frontline roles. That compares with only about 16 per cent of clerics and administrators in Western Australia’s public service, or 9 per cent in the NSW public service. More than 3 per cent of the Territory’s bureaucrats are executives compared with less than 1 per cent in Victoria’s.

Despite these startling figures and insider accounts of a bureaucratic culture based on spending targets rather than savings (and the prospect of insolvency within a decade), no politician of any stripe has yet committed to sacking any public servants.

“The government must ensure that government services are delivered efficiently and that everyone is working to deliver services or increase opportunity,” Finocchiaro says, dodging repeated questions about public sector waste.

Manison promises to talk to stakeholders “about reforms that will create local jobs, drive more efficient government services and fix these budget issues.”

“What we will not do is take the CLP approach of sacking teachers and nurses, selling government assets (like TIO) and hiking up the price of power by 30 per cent,” she says. “We will be smarter than their slash and burn approach, and we will focus on creating jobs.”

Both major parties fear the electoral cost of shrinking the public sector under what is now effectively a patronage system. Public sector cuts also could hit population growth. The government has estimated each Territorian to be worth about $11,000 in GST.

So keen is the Gunner government to curb population decline that it is offering cash bonuses to people who move north. It has announced a variety of debt-funded stimulus schemes but, so far, has not been able to attract any major new private sector projects.

The budget report talks about “shifting the mindset of the public sector towards a single enterprise focus to improve productivity, minimise duplication and provide a more agile service” without suggesting how that may be achieved. Expenditure growth is to be halved through unspecified means and a return to surplus pushed out to the late 2020s, even under favourable assumptions.

Gerritsen says the Territory is en route to “Italian or Greek levels of debt”.

“The scenarios presented (as a fix) are inadequate because they presume that the public sector will continue to grow when it should shrink by 40 per cent,” Gerritsen says.

“We are growing our debt at double the national rate … we have one-third greater expenditure on grants and subsidies, showing we need to stop subsidising boat ramps, football teams and tradesmen.”

None of those options looks likely at the moment, largely for want of political leadership. In their absence, Elferink has another solution in mind — repealing the Territory’s self-government act.

“The new state of Centralia, an amalgam of SA and the NT,” he proposes. “A state with resources to rival WA. A dissolution of the south-north divide that has been a cultural Mason-Dixon line in Australia. In the Asian century, it is time to put Australia firmly in Asia.”

As he wryly notes, the undignifying option would have the side benefit of granting all Territorians “full state’s rights for the first time since 1911”.

It’s not quite the outcome for which good governments might have hoped.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout