Millennial socialists chip away at the virtues of liberalism

Misdiagnosis and poor prescriptions by a new breed of millenial socialists offer no relief for the West’s fractured societies.

When the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989, many consigned socialism to the rubble. The end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union were interpreted as the triumph not just of liberal democracy but of the robust market-driven capitalism championed by Ronald Reagan in the US and Margaret Thatcher in Britain.

The West’s Left embraced this belief, with leaders like Tony Blair, Bill Clinton and Gerhard Schroder promoting a “third way”. They praised the efficiency of markets, pulling them further into the provision of public services, and set about wisely shepherding and redistributing the market’s gains.

Men such as Jeremy Corbyn, a hard-Left north London MP as far from Blair in outlook as it was possible to be, and Bernie Sanders, a left-wing mayor in Vermont who became an independent congressman in 1990, seemed as thoroughly on the wrong side of history as it was possible to be.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was not quite four weeks old when the wall fell. Her childhood was watched over by third-way politics; her teenage years were a time of remarkable global economic growth. She entered adulthood at the beginning of the global financial crisis. She is now the youngest woman to serve in the US congress, the subject of enthusiasm on the Left and fascinated fear on the Right. And, like Corbyn and Sanders, she explicitly identifies herself as a socialist.

The Left today sees the third way as a dead end. Their democratic socialism goes considerably further than the market-friendly redistributionism of Blair and Clinton. It envisages a level of state intervention in previously private industry — either directly or through forced

co-operativisation — that has few antecedents in modern democracies.

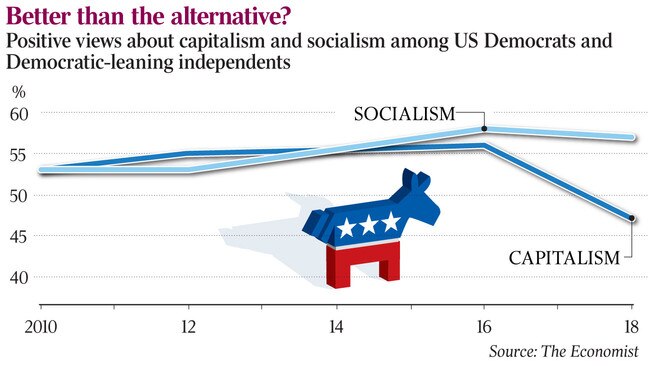

Many of the new socialists are millennials. About 51 per cent of Americans aged 18-29 have a positive view of socialism, says Gallup. In the primaries in 2016 more young folk voted for Sanders than for Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump combined. Almost a third of French voters under 24 in the presidential election in 2017 voted for the hard-Left candidate. But millennial socialists do not have to be young. Many of Corbyn’s keenest fans are as old as he is.

Not all millennial socialist goals are especially radical. In the US one policy is universal healthcare, which is normal elsewhere in the rich world, and desirable. Radicals on the Left say they want to preserve the advantages of the market economy. And in Europe and the US the Left is a broad, fluid coalition, as movements with a ferment of ideas usually are.

Nonetheless, there are common themes. The millennial socialists think that inequality has spiralled out of control and that the economy is rigged in favour of vested interests. They believe that the public yearns for income and power to be redistributed by the state to balance the scales. They think that myopia and lobbying have led governments to ignore the increasing likelihood of climate catastrophe. And they believe that the hierarchies that govern society and the economy — regulators, bureaucracies and companies — no longer serve the interests of ordinary folk and must be “democratised”.

Some of this is beyond dispute, including the curse of lobbying and neglect of the environment. Inequality in the West has, indeed, soared during the past 40 years. In America the average income of the top 1 per cent has risen by 242 per cent, about six times the rise for middle-earners. But the new Left also gets important bits of its diagnosis wrong, and most of its prescriptions, too.

Start with the diagnosis. It is wrong to think that inequality must go on rising inexorably. American income inequality fell between 2005 and 2015, after adjusting for taxes and transfers. Median household income rose by 10 per cent in real terms in the three years to 2017. A common refrain is that jobs are precarious. But in 2017 there were 97 traditional full-time employees for every 100 Americans aged 25-54, compared with only 89 in 2005. The biggest source of precariousness is not a lack of steady jobs but the economic risk of another downturn.

Millennial socialists also misdiagnose public opinion. They are right that people feel they have lost control over their lives and that opportunities have shrivelled. The public also resents inequality.

Taxes on the rich are more popular than taxes on everybody. Nonetheless, there is not a widespread desire for radical redistribution. Americans’ support for redistribution is no higher than it was in 1990, and the country recently elected a billionaire promising corporate tax cuts.

By some measures Britons are more relaxed about the rich than Americans are.

If the Left’s diagnosis is too pessimistic, the real problem lies with its prescriptions, which are profligate and politically dangerous. Take fiscal policy. Some on the Left peddle the myth that vast expansions of government services can be paid for primarily by higher taxes on the rich. In reality, as populations age it will be hard to maintain existing services without raising taxes on middle-earners.

Ocasio-Cortez has floated a tax rate of 70 per cent on the highest incomes, but one plausible estimate puts the extra revenue at just $US12 billion ($17bn), or 0.3 per cent of the total tax take. Some radicals go further, supporting “modern monetary theory”, which says that governments can borrow freely to fund new spending while keeping interest rates low.

Even if governments have recently been able to borrow more than many policymakers expected, the notion that unlimited borrowing does not eventually catch up with an economy is a form of quackery.

A mistrust of markets leads millennial socialists to the wrong conclusions about the environment, too. They reject revenue-neutral carbon taxes as the single best way to stimulate private-sector innovation and combat climate change. They prefer central planning and massive public spending on green energy.

Millennial socialists have their own ideas about freedom, too. They are not satisfied with the protection of existing freedoms; instead, they want to expand and fulfil freedoms yet to be obtained. Spreading economic power more widely, they say, will allow more people to make choices about what they want in their lives, and freedom without such capabilities is at best incomplete.

Bhaskar Sunkara, founding editor of Jacobin, makes an analogy to India: what is the point of an ostensibly free press if a huge share of the population is unable to read?

Much of what the centrist Left believed in the 1990s and 2000s has since been abandoned, not just by vanguardist millennial socialists but by a broad swath of left-wing opinion. The median supporter of left-wing parties is increasingly sceptical about free trade, averse to foreign wars and distrustful of public-private partnerships.

What they still like is the income redistribution that came with those policies. They want higher minimum wages and a lot more spending on public services.

Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez have energised young Americans by promising free college tuition; Labour promises the same in England and Wales.

Many entirely non-socialist Europeans will see nothing that remarkable about publicly paid-for healthcare and education: America starts from an unusual position in such matters. But almost any country would be staggered by a government initiative as all-encompassing as the Green New Deal resolution that Ocasio-Cortez and Ed Markey, a senator from Massachusetts, have introduced into congress.

As well as promising emissions-reduction efforts on a scale beyond Hercules at a cost beyond Croesus, in framing global warming as a matter of justice rather than economic externalities, it promises all sorts of ancillary goodies, including robust economic growth (which some hardline greens will have a problem with) and guaranteed employment.

It abandons the economically efficient policies that have been the stamp of America’s previous, failed attempts to bring climate action about through legislation. This is hardly surprising; the most popular text on global warming in left-wing circles, Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate, derides such market-based mechanisms.

Millennial socialists want to do more than boost the incomes of the poor, create better public services and slash emissions. “Keynesianism is not enough,” in the words of James Meadway, an adviser to John McDonnell, Corbyn’s shadow chancellor. It is also necessary to “democratise” the economy by redistributing wealth as well as income.

The millennial socialist vision of a “democratised” economy spreads regulatory power around rather than concentrating it. That holds some appeal to localists, but localism needs transparency and accountability, not the easily manipulated committees favoured by the British Left.

If England’s water utilities were renationalised as Corbyn intends, they would be unlikely to be shining examples of local democracy. In the US, too, local control often leads to capture. Witness the power of licensing boards to lock outsiders out of jobs or of Nimbys to stop housing developments. Bureaucracy at any level provides opportunities for special interests to capture influence. The purest delegation of power is to individuals in a free market.

The urge to democratise extends to business. The millennial Left wants more workers on boards and, in Labour’s case, to seize shares in companies and hand them to workers. Countries such as Germany have a tradition of employee participation.

But the socialists’ urge for greater control of the firm is rooted in a suspicion of the remote forces unleashed by globalisation. Empowering workers to resist change would ossify the economy.

Less dynamism is the opposite of what is needed for the revival of economic opportunity.

Rather than shield firms and jobs from change, the state should ensure markets are efficient and that workers, not jobs, are the focus of policy.

Rather than obsess about redistribution, governments would do better to reduce rent-seeking, improve education and boost competition. Climate change can be fought with a mix of market instruments and public investment.

Millennial socialism has a refreshing willingness to challenge the status quo. But like the socialism of old, it suffers from a faith in the incorruptibility of collective action and an unwarranted suspicion of individual vim.

Liberals should oppose it.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout