Leave the surplus champagne on ice for the moment

The forecast is too tiny and still too far away to justify rejoicing over an improvement in the fiscal outlook.

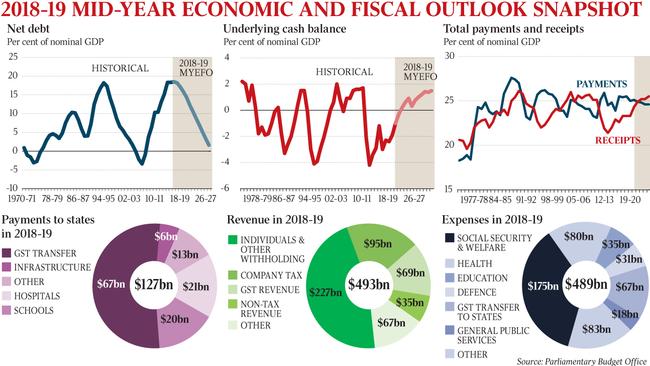

In two years, for the first time since the global financial crisis of 2008, the federal government’s receipts may exceed its outlays by a margin of 0.8 per cent.

That’s assuming China’s economy continues to power ahead, the trade war with the US fizzles out, wage growth accelerates to 3 per cent and the economy shrugs off sharp falls in house prices in its two biggest cities.

Put like that, the fanfare surrounding the prospect of a $4.1 billion surplus in 2020, announced in yesterday’s mid-year budget update, is a little odd. This would be a rounding error for a government expecting to collect $506bn in that year, and would follow a string of deficits that have seen the commonwealth’s net debt almost double to about $350bn since the Coalition won office in 2013.

The government’s fiscal position remains precarious, weighed down by the costs associated with an ageing population alongside an increasingly complex and inefficient tax system that has benefited from a boom in jobs and company profits, in part stemming from unexpectedly strong iron ore and coal prices thanks to China’s continual outperformance.

Although parliament repeatedly has thwarted its tax and welfare reforms, the economy, domestic and global, has been kind to the Coalition government. The jobless rate has continued to edge down, in keeping with a powerful global trend towards strong jobs growth in parallel with meagre wage rises.

“Payments related to income support for jobseekers are down by over $1bn over the next four years as the number of Australians of working age on welfare is at its lowest level in 25 years,” Josh Frydenberg noted yesterday.

But the housing market has clearly slowed dramatically, with still unknown ramifications for household confidence and job growth.

It isn’t only state governments, reeling from a one-third drop in sales volumes, whose stamp duty revenues dry up. The federal capital gains tax haul is estimated to be $16.6bn this year, down $100 million since May.

The federal election expected in May probably will sap whatever fiscal strength is emerging. “Both sides of politics plan to spend the revenue bonus but still commit to surpluses. This is a risky strategy, as revenue surprises rarely last,” says Annette Beacher, head of TD Securities,

Yesterday’s budget update, the last until Treasury reveals the pre-election fiscal outlook required by the Charter of Budget Honesty, also trimmed economic growth from 3 per cent to 2.75 per cent for this year, slashed business investment growth by two-thirds to 1 per cent, and cut the expected rate of home building by a third.

For the government, though, the figures “confirmed the strength of the Australian economy and the health of the nation’s finances”, pointing to the expected fall in net debt from the equivalent of 18.5 per cent of gross domestic product last year to 1.5 per cent in 2029.

Such an improvement is contingent on the fanciful assumption that underlies every budget: no new spending. Via “decisions taken but not yet announced”, the government has made provisions for tax cuts of up to $9.2bn before, and extra spending of $1.4bn over, the next four years. These are piddling sums given Canberra’s coffers are expected to enjoy $2.07 trillion of receipts across the same four-year period.

For all Labor’s talk of “bigger surpluses sooner”, political reality in Canberra — combined with the opposition’s determination to lift spending — presents a significant risk to the budget.

“I would rather help older Australians get more speedy elective surgery, and the aged-care package they need, than spend $5bn on an income tax refund for people who didn’t pay any income tax that year,” Bill Shorten told Labor’s national conference in Adelaide over the weekend.

The problem is Labor’s swag of tax hikes — including his referenced ending of the refundability of franking credits and lifting the top marginal tax rate to 49 per cent — will face stiff resistance in the Senate.

By contrast, Labor’s almost as hefty spending plans are likely to be welcomed in the upper house. As well as shovelling even more funds at schools, hospitals and TAFEs, the Opposition Leader called for “new investments in infrastructure, tourism, advanced manufacturing, defence industry, rail and renewable energy”.

Yesterday’s surplus celebrations were all the more curious given the route taken to get there. If a government increases taxes every year, eventually it will return the books to surplus.

From a record low of 19.9 per cent in 2009 (the same share as in 1975, the last year of the Whitlam government), federal tax collections as a share of GDP have increased steadily every year to 23.1 per cent this year, on the way to 23.8 per cent across the next four years, according to the latest budget estimates.

Were the tax office to be collecting the same share of wages and salaries as tax in 2020 as it did in 2013, when the Coalition won office, the budget would be facing a $17bn deficit in 2020 rather than a $4.1bn surplus.

“This surplus isn’t happening because spending is going down,” says Access Economics’ Chris Richardson. “The key drivers of that are a lift in company taxes thanks to better than budgeted coal and iron ore prices, plus an upsurge in personal tax collections as bracket creep runs ahead of recently announced tax cuts.”

Middle-income workers face almost a seven percentage point increase in their average tax rate by 2021 compared with 2009: for a worker on $75,000 a year, that’s a $101 a week in additional tax.

The four income tax thresholds in 2008 were $6000, $34,000, $80,000 and $180,000. Had they kept pace with prices they would now be $7376, $41,795, $98,341 and $221,266. Had they kept up with wages, which tend to rise faster than prices, the top two rates would be $104,974 and $236,192.

The part of the government’s seven-year tax plan most resisted by Labor, lifting the top income tax threshold to $200,000 in 2024, was in effect simply a small reduction in the planned tax increase the government has pencilled in.

The Coalition has made a lot of its restraint and rectitude but reality is somewhat different. “In accordance with our disciplined budget management, new spending has been offset by reduced spending elsewhere and the payments-to-GDP ratio is falling to 24.6 per cent by 2021,” the Treasurer said yesterday.

Spending as a share of the economy has fallen a little from a peak of 25.5 per cent in 2016, second only to the 25.9 per cent reached in 2009 when Labor unveiled a fiscal stimulus worth $54bn. But a constant share of a growing economy still spells dramatic increase.

In the six years from 2012, federal government spending has increased 31 per cent, from $367bn to $484bn, while the population has increased by 9.7 per cent to almost 25 million.

“The rate of real spending growth under the Coalition is averaging 1.9 per cent, the lowest level of any government in 50 years,” the government says.

Yet spending growth this year alone has blown out to 4.8 per cent, up from the 3.1 per cent growth pencilled in back in May.

To be sure, the Rudd-Gillard years left fiscal poison pills — a big increase in the Age Pension in 2009, for instance, and the blowout-prone National Disability Insurance Scheme — but the Coalition nevertheless has presided over accelerating growth in spending. To take one example, its childcare reforms supercharged what was already a growing torrent of support, including to families where one partner isn’t working. It would have been still more generous had the Liberal Democrats not insisted the largesse peter out at family incomes of $351,000.

Following the tough 2014 budget, federal real spending shrank 0.3 per cent, something that has happened only three times in a generation. That was the first full year of Coalition government.

The next year real spending growth rose by 1.3 per cent, then by 2 per cent, and now, as mentioned, by 4.8 per cent, the most rapid rise since Wayne Swan’s last budget.

Professional analysts’ views of the budget update are mixed.

“Overall, there were no major surprises in today’s budget update. A testament to the improvement in the broader economy, Australia’s public finances are in their best shape for many years,” Goldman Sachs chief economist Andrew Boak says.

Barclays’ Rahul Bajoria says: “The underlying public finances in Australia remain in very good shape. While we do not necessarily agree with three years of projected rising surpluses, fiscal space is opening up significantly.”

Citi’s chief economist Paul Brennan says “the improvements are modest at best”.

“They could be whittled away as the government announces new spending priorities ahead of the May 2019 federal election — meaning this set of budget numbers could be as good as it gets,” he points out.

Westpac’s chief economist Bill Evans says: “Consumer spending, residential construction and wages growth are likely to be weaker than forecast in the budget update, while uncertainty around the upcoming federal election and global trade tensions might unnerve businesses.”

On a different measure, the budget won’t even be in surplus in 2020. The so-called “underlying cash balance”, which grabs the headlines, ignores expenditures on certain government-owned corporations.

The headline balance, by contrast, includes a much bigger range of government incomings and outgoings. Think of the debt and equity investments in NBN, Western Sydney Airport, the Melbourne to Brisbane railway and Snowy 2.0, for instance.

On this measure, the budget still will be in deficit in 2020, to the tune of $7.1bn, following an $18.4bn deficit this financial year.

Maybe we need to put the champagne on ice for another year.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout