Katowice climate conference: Ambition keeps burning

The Poland climate change talks were mostly about keeping alive the hopes engendered by the Paris Agreement.

As talks ground on in Katowice and the deadline neared for negotiators to agree on key details to bring the Paris Agreement to life, the decision that everyone had been waiting for finally was made.

Next year’s Conference of Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change will be held in Chile with a pre-conference in Costa Rica, a welcome tropical change from the snow and cold of Poland.

The Katowice COP24 had been dogged by the decision by Brazil’s president-elect Jair Bolsonaro to withdraw his country’s agreement to host the travelling climate circus next year. Bolsonaro stopped short of following US President Donald Trump out of the agreement altogether. But against a background of riots in France, sparked by the heavy cost of the green transition, a sense of pending doom was never far from the mind in Katowice.

In the end, Brazil scuttled any chance of agreement on the rules for future carbon trading markets by insisting carbon offsets could effectively be double counted.

But the real contest has always been between the developed and developing world over money on the one hand and shared commitment on the other.

Australia will be happy with the outcome. There will be pressure to give more money to the Green Climate Fund but significant issues about governance remain.

The federal government will not be required to change its existing timetable on lifting its Paris Agreement targets. But there will be added pressure to give more detail about climate finance more generally into the future. The conference agreed to a new process from 2020 to decide how to lift the agreed finance past $US100 billion ($139bn) a year.

The positive for developing countries is that there is now a single, strict rule book that covers all countries.

The COP is a high-stakes game. For purists it is all about saving the world from what scientists warn will be the heavy consequences of rising global temperatures caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

Noam Chomsky sent a video message, following up on David Attenborough’s warning of the existential threat that opened the COP. “We face a very serious dilemma, stark, cruel dilemma,” said Chomsky. Climate change was “the most important issue that has arisen in human history”.

For developing countries, the UNFCCC process remains the last and best chance at multilateralism to push a broad range of social justice and equity issues.

And that explains why, after two weeks of talks, agreement was reached on the most substantive issues needed to bring the Paris Agreement into force.

In essence the dynamic has always been what liabilities developed nations are willing to shoulder to encourage developing nations into a single agreement.

For non-government organisations and particularly small island states, the drumbeat of “ambition” has become the benchmark against which success or failure can be judged. Much of the theatre in Poland, if not the substance, had been around how to incorporate the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report on 1.5C warming.

The difference between “noting” the IPCC report and “welcoming” the report may seem semantic.

But it reflected the push by some countries to insist the report anchor the Paris Agreement and call for an immediate lift in measures by all countries to curtail carbon dioxide emissions.

Australia had argued the timetable for ambition was set in Paris, with countries obliged to indicate their plans in 2020.

And this is what COP24 agreed.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has called a special conference in New York next September. UNFCCC executive secretary Patricia Espinosa says her five aims at that meeting will be ambition, ambition, ambition, ambition and ambition.

In Katowice, developed countries, including Australia, argued solid rules and clear guidelines were needed to make higher ambition possible.

Towards the end of negotiations, Environment Minister Melissa Price told The Australian there were “two tribes” within the climate talks.

“Sometimes it is clear that it is developing and developed countries, but other times it is more confusing,” she said.

Price says Australia believes it is in the best interests of the Paris Agreement that there be full transparency on what all countries are doing.

“If you don’t have transparency you can have high ambition,” she says. “But if we are not all measuring and accounting and reporting the same, then what is the point?”

Price left Poland before the end of the talks.

But after the successful conclusion, Australia’s ambassador said on behalf of the Umbrella Group representing developed countries including Japan and the US that the meeting achieved “a clear signal to move forward in the spirit of Paris”.

China and India remained determined throughout talks to preserve for developing countries the right to continue on the road of economic transformation.

In the end, the US and its developed country partners appeared to be more satisfied than most others.

Indian media was reporting that attempts by developed nations to dilute differentiation represented backsliding by them on what had been agreed to in Paris.

For developed country negotiators it was China, India and other developing countries that had misinterpreted the intent of Paris. Friends of the Earth campaigner Meena Raman provides an insight into the thinking of the developing world.

“In Paris it was very hard-fought on the different responsibilities in light of national circumstances,” Raman says. “How the US interprets that and how the developing countries are interpreting that is the clash.”

This issue has an extended history in the UNFCCC process. The Durban meeting in 2011 agreed to negotiate the Paris Agreement after an angry last-minute clash in which India said it would not proceed without a clear understanding that different countries would face different obligations.

Then US secretary of state John Kerry closed the deal on the Paris Agreement in 2015 by threatening to withdraw the US from talks if the developing world continued to insist on differentiation or a bifurcated process.

At the conclusion to the Katowice talks, Egypt, on behalf of the G77 countries plus China, told the conference: “Unfortunately we do not see the level of balance we have consistently called for.”

It said the urgent development needs of the developing countries had been relegated to “a second-class status”. The Egyptian statement was echoed by India, Malaysia and others.

Nonetheless, India says the Katowice decision signified the success of the multilateral forum and reinstated its faith in it to find solutions to global problems.

But it says: “We must recall our commitment to equity to ensure climate justice to the poor and vulnerable people across the globe.”

Malaysia, on behalf of lesser developed countries, was more outspoken.

“We simply cannot ignore the past to understand the present and plan for the future,” Malaysia says.

“It is crucial to understand why developed countries are developed and we are developing.

“The largest share of the carbon budget has been utilised by western Europe and northern America as they industrialised, fuelled by the use of fossil fuels. This was the genesis of climate change.

“Developing countries want to develop, and for this the remaining carbon space must be shared equitably.”

In reality, developing nations won’t abandon UNFCCC talks because there is potentially too much at stake.

“The Paris Agreement is the only multilateral process left where you can insist on commitments of developed to developing countries because of historical responsibilities,” Raman says.

“We walk away from here, we let them get off the hook. Those who have the responsibility should be held to account and this is the process we have to hold them to account.”

Price’s message to the conference was “we must act together because climate change affects us all and Australia must play its part”.

She says Australia is on track to meet its 2030 target, which represents a halving of emissions per person.

Action groups dispute that Australia is on track to meet its 2030 target of 26 per cent to 28 per cent below 2005 levels and they accuse it of using sharp accounting practices by booking over-achievement in the Kyoto agreement towards the 2030 target.

But Price says the federal government will not be intimidated into bringing forward its timetable to announce further cuts.

“We are comfortable where we are now,” she says. “We are not intending to even review that until 2020. Our focus in Katowice is on the quality of the rule book.”

Australia’s position was confirmed by the Poland COP.

The disappointment expressed by climate action groups after the meeting was that it did not push for immediate higher targets.

Climate Action Network says governments failed to respond with the political will to tackle the urgency of the climate crisis informed by the latest science.

“The overbearing presence of the fossil fuel industry combined with a weak Polish presidency cast a shadow over these talks,” it says.

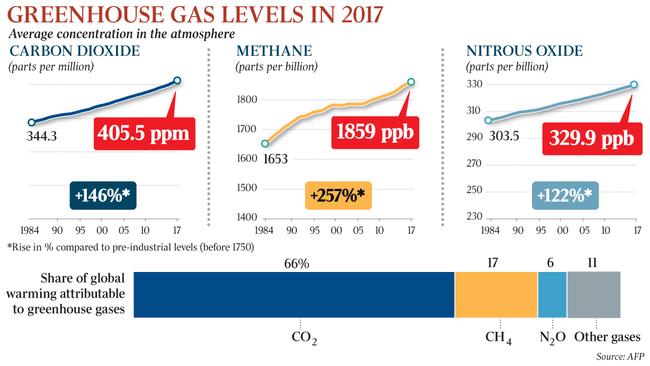

The reality is few countries are meeting their existing commitments. Germany is well off target for 2020 and, according to reports released at the Katowice conference, global greenhouse gas emissions are back on the rise at an accelerating rate.

The outgoing COP president, Fijian Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama, says: “The world must take heed of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5C above pre-industrial levels and take dramatic and urgent steps to decarbonise the global economy and assist those at the frontline of climate change impacts.”

Small island states called for all OECD countries to phase out their use of coal by 2030, and for all other countries to phase it out by 2040.

“There must be no expansion of existing coalmines or the creation of new mines,” they say.

European Climate Foundation chief and former French negotiator Laurence Tubiana says the UN meeting in September 2019 will be “a very important political moment”.

She says a single rule book is a condition for raising ambition over time.

“Ambition is 2020, not now,” she says.

The mega trend, according to Tubiana, is that the real economy is starting to influence the mindset of government.

Leading carmakers are shifting to electric vehicles, and the world’s largest shipping company, Maersk, has pledged to be carbon-neutral by 2045.

Corporate decision-makers are falling over themselves to be on the right side of the debate. The travel industry and fashion have both pledged global efforts for carbon neutrality.

The finance sector is writing new rules that will make it hard to raise capital for sectors that are considered not to be acting in accordance with the Paris Agreement ambitions.

“All that is happening in the real economy will begin to be translated in government policy and recognition,” Tubiana says.

Another trend in Katowice has been the concerted effort to mobilise the youth.

“It is interesting the young people are now saying ‘stop it, you are not serious’, and the mobilisation of the young generation is really taking up”, Tubiana says.

“We end this bickering on the details (of the Paris Agreement) and we are beginning to focus on what is really important, which is how we transform the economy supported by a powerful movement of civil society and youth that will really make companies and governments accountable for what they are doing.

“This is in my view the new phase.”

Chomsky agrees. “To combat climate change we need much more than government, we need society,” he says.

“That is why we are now entering a very interesting phase”.

The actual face of protest doesn’t appear to have changed all that much.

Camped out on the main staircase during the conference was a rainbow coalition comprising men in suits, a man wearing a florid dress with purple hair, another in a bowler hat with full beard, and women from Brazil with war paint, giving evidence from places where protest can cost you your life.

For some, however, the key message was lost in translation.

“System change not climate change,” read the protest banner.

Looking at the group from below, a delegate from Japan read the banner and asked out loud: “What does that mean?”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout