John Howard on the Tampa refugee issue and the 9/11 attacks in Washington and New York

FORMER prime minister John Howard explains why he turned back Tampa in 2001, and recalls being in Washington on 9/11.

Howard Defined, episode three.

This is a transcript of the series originally recorded in 2014 for Sunday Night on Channel Seven, and broadcast in full on Sky News in January 2015. See the episode here.

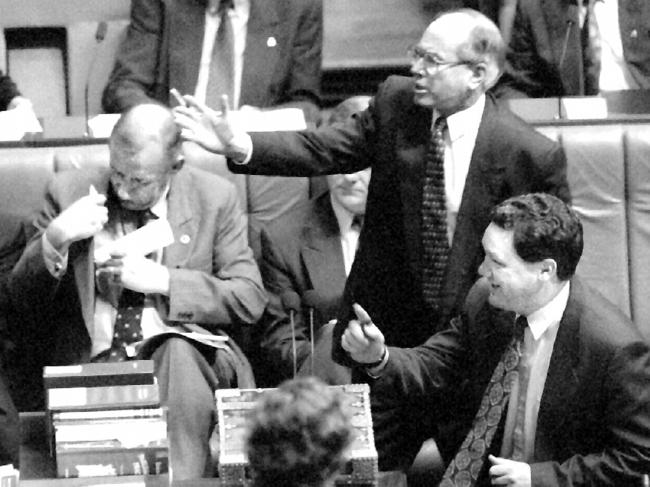

Janet Albrechtsen: You have been in Old Parliament House recently. You are very fond of it.

John Howard: Yeah, I am very fond of it. I like the debating chamber. It’s smaller, more intimate, warmer. You could almost reach out and touch people, not in a belligerent way. The new parliament or the permanent Parliament House chambers are too big and cavernous.

And what are your fondest memories?

My fondest memories of the Old Parliament House were the debates, without any doubt. Well, as treasurer, as opposition leader, I really enjoyed those debates enormously. They had a character about them, they had an intimacy about them.

Was there humour?

There was humour but never as much as legend has it.

Paul Keating was pretty funny.

Paul Keating was funny, yes.

Did the barbs ever hurt, though?

No. Well, I developed ... the skin was pretty thick by then (laughs). And I had been insulted by experts.

In 1989, you were tossed out of the leadership. What was the chance of you returning to the leadership?

Ahh, zero. Zilch. I described it at my press conference when I was asked, “Do you think you will ever come back?” I said, “That’s like Lazarus with a triple bypass.” That expression passed into the political lexicon and it did come to pass but I didn’t think it would, and I certainly didn’t think it would on the 9th of May 1989. I had been unceremoniously and very heavily dumped. I think the vote was 44 to 27. That’s decisive in anybody’s language. I thought that was the finish of me in a leadership position.

When I watch that press conference there is the Howard front, the brave front. But there is obviously the man behind the camera. What happened behind the camera when the cameras were turned off?

Well, I was very disappointed. I was upset, I was angry, I felt a number of people could have come to me and said, “Look, you are on the skids, John, unless you lift your game or if you do this or that,” but it didn’t happen. I mean it was a cleverly executed coup, there is no doubt about that. You had to give them 10 out of 10 for guile.

You then went into what we know as the wilderness years. Were you still sounding out for the leadership?

Immediately after the 1990 election I had a conversation with Peter Reith who was a very close friend of mine and he said very bluntly to me, “John, forget it. The party wants to move on from you and from Andrew. That is all behind us. They want a new generation.”

John Hewson lost what was classified as an unlosable election for the Liberal Party. You stood for the leadership after that election but you were rejected.

Yes, I was once again quite decisively rejected.

Are you getting good at rejection at this stage?

Very good at rejections, very good. You know I could write a PHD thesis on rejections.

How long does it take Lazarus to get back on the leadership horse? When you say that it’s over and you said it a few times — 89, 90, again in 93, you think it’s over, how long does it take you? Is it days, is it weeks before again you start thinking, “No, I want that leadership”?

Well, I don’t think I ever abandoned the desire to have the leadership, to be perfectly honest, of course I didn’t. Anybody with ambition who has held the leadership of a political party never if they are honest with themselves abandons the desire to have it again.

So Lazarus starts rising. Tell me how the leadership came to be yours in early 1995.

Well, it was obvious by Christmas of 94 that one way or another the leadership issue would come to a head.

You had had a dinner with Alexander Downer though, hadn’t you?

What happened was, the final moments were we had a meeting of the shadow cabinet in Dandenong in Victoria and then Alexander and I had a meal at the Athenaeum club in Melbourne and I said Alexander, “I have to tell you that if there is a not a leadership transfer I will challenge.” It’s not something I wanted to do, I had taken the view having tried before on a number of occasions and failed the best thing would be for there to be a draft of the leadership.

So did you tell him that his leadership really was terminal?

Yeah, I told him. Yes, I did.

How did he take that?

He was very calm about it. I think he probably understood that. He behaved magnificently and he really did put the interest of the Liberal Party ahead of his own feelings. I think the Liberal Party owed him an enormous debt of gratitude. It’s something that I never forgot in the years that followed. The following day he asked me to go around to his office and he said he had decided to surrender the leadership; he said he wanted a couple of days to find the right moment to announce it, he wanted to do it in Adelaide with his family and I said, “Of course.”

How did you feel when he told you that?

I felt quite ... it was a feeling of contained elation.

Was there something to be said for being the last man standing?

That is an interpretation but you have got to, you’ve got to have some standing to be the last man standing.

What kept you going, though? It is unusual ...

What kept me going was that I was still very committed to politics, I was still intensely interested, I still wanted to change things. I still believe that I was good at politics

And good enough to be prime minister.

I did, of course I did. I saw my opponent ... I knew Paul Keating very well in a political sense and I knew Bob Hawke very well and I thought Keating was eminently beatable.

Let’s move on to the 1996 election. You were sure of winning that election ...

All the objective criteria told me I would win but in here I was still as nervous as anything. But of course as soon as the results started coming in it was obvious that we were going to win and win very heavily.

Where were you that night as the numbers were coming in?

We organised some rooms at the Intercontinental Hotel in Sydney and Janette and I invited some of our close friends and family for what we hoped was going to be a great night. At about 6.20pm the commission spotted a return from a tiny little booth in Portland East in the country area of NSW and it showed something like an 18 per cent swing to the Liberal Party, and I said, “Terrific!” Grahame Morris said, “Hang on, tiger. There is only 80 votes in that booth so don’t get too excited.” But by 7pm it was apparent that we were going to win.

Where did the term “Howard battlers” come from?

It came from the way in which I related to a lot of people in the electorate. I, by my language and my attitude and my policies, paid particular respect for people who battled in their lives to not only keep their jobs and in some cases start a small business but raise their families, give their families a better start in life.

Because it is noticeable that there were no “Fraser battlers”, for example, or “Holt battlers” or “Snedden Battlers”. There were “Howard battlers.”

I think one of the explanations for that is that in the time that I was prime minister I was able to unlock support for the Liberal Party for many people who had previously come from Labor-voting families.

Do you think when the current treasurer, Joe Hockey, in a sense didn’t pay much respect to the concerns of what he called poor people and concerns over petrol prices that he was almost ignoring Howard battlers?

I don’t think he set out to do that but that was a very bad statement and he apologised, which is more than I have heard from people on the other side who made gross statements like that. They could never bring themselves to apologise. I thought Joe showed a lot of guts in apologising. That was a silly statement, of course. Everybody knows that.

You were constantly underestimated so often throughout your career — you were the bowser boy, you were the budgerigar salesman. Did it help you to be underestimated?

I think it probably does help you because it is always better to surprise on the upside than the downside (laughs). I think people who go into positions with soaring reputations, there can often be intense disappointments. I do think it’s better, to use the old cliche, to under promise and over deliver.

But is there a leadership lesson there, do you think, in not over-promising?

I think leadership lesson for all of us is that you have got to have a clear set of beliefs and you have got to stick to them. I think the greatest political mistake Kevin Rudd made was not to try and stare down the opposition and Tony Abbott on the issue of climate change. He said that it was the greatest moral challenge of our age. Well, having said that, he had to act as though he believed it, and he didn’t. That was his great mistake. If he had acted as though he believed that, he might still have been there now.

What did you make of the recent revelation in Wayne Swan’s book that Kevin Rudd had gone out and asked the Labor polling people to “find me a core value”?

Oh, extraordinary.

Is that something you ever did?

Look ... if you don’t have a philosophy and a set of values then you will inevitably bungle the job of prime minister of this country.

People work you out.

People do work you out. Australians are very intelligent. They are very savvy. They don’t like humbug, they don’t like phonies, they don’t mind a person being passionate about something. They don’t necessarily support (that person) provided that they (can) get on with their own lives. But when somebody demonstrates a lack of conviction and consistency, they lose interest.

So they worked out that Kevin Rudd was a phony, do you think?

I think they did and I think the climate change thing killed him.

Let’s turn to Port Arthur. Just after 1pm on the 28th of April 1996 you would have to face a national trauma, which was the mass killing of 35 people in Port Arthur in Tasmania. Where were you when you heard about that?

I was at Kirribilli House when I heard about it.

Who rang you?

I was rung by, somebody in my press office rang me. I didn’t have the television on at the time. I don’t know what I was doing. I was probably just signing letters and papers in my study and somebody from the press office rang and said you better put the television on, and the details started to unfold.

And what happens in your head and your heart in that moment when you hear?

I knew immediately what an enormous tragedy it was but I immediately started thinking, “What can I do?” I had just become prime minister. I had this colossal mandate — the early weeks you have a honeymoon period. The public will accept things from you, they have decided to get rid of another government decisively, they want you to do the right thing and I thought, “What can I do?” I immediately started thinking about what the federal government might do. I talked to Tony Rundle briefly about Tasmanian gun laws. He agreed that they needed to be tightened and I thought, there has to be a role. I then went down to Tasmania in the next couple of days and I invited Kim Beazley, the leader of the Labor Party, and Cheryl Kernot, the leader of the Democrats, to come with me. We went to Port Arthur and we laid a wreath as a trio in memory of the people who had died. I then went to a memorial service at the Anglican cathedral in Hobart and met the medical staff. I remember talking to one of the doctors who was quite emotional and I embraced him and consoled him. He was so distressed about the injuries he had treated, and I formed in my mind then a determination to try and do something.

I was getting bits and pieces of advice and my department and my staff were, “Oh well, John this is largely a state matter.” I thought, “Well no, it’s more than that. This is the single biggest death toll from a mass shooting from an individual in world history in peace time.”

Daryl Williams, the attorney-general, raised the possibility of having a prohibition which would be brought about by a uniform state legislation, and the federal government would buy back the guns. At one stage Daryl came to me and said, “Look, I don’t think we’re going to make it. Perhaps we should settle for something less.” I said, “No, I don’t want to settle.” I then met all of them and most of them were supportive and some of them were reluctant. I can understand it. It was a very difficult decision for the National Party government in Queensland.

People were worried ... that some maniac would do that in their street. I could understand it. And the reaction, particularly from women … I remember one woman coming up to me in Sydney in the street not long after and she said, “I never voted for you in my life and I don’t think I ever will but gee I agree with you on what you’re doing with guns.” In a funny sort of way I got a sense of pride out of that. But it was very hard for the National Party because the laws affected a lot of farmers doing what they regarded as perfectly legitimate things. They had weapons that were caught up with the prohibition and they said, “Well hang on, I’m not going to shoot anybody. I’ve looked after the weapons carefully and so forth.” But you had to you had to apply it to everybody. It was one of the things that helped give fire and brimstone to One Nation when it ultimately came along because a lot of people who supported Pauline Hanson were grieved what we had done over guns.

Apart from the conviction that Australians saw early on, they saw another side to John Howard, didn’t they? They saw a person who was able to mourn on behalf of the country.

No, that’s true. I remember that occasion when I embraced that doctor. It just seemed the human thing to do. I thought to myself, “Well, he’s upset. This will help.” I knew instinctively that if you felt you should do that you shouldn’t hold back because you’re in public ... Some people responded to that very positively, some almost by their own body language or how they look at you — well, a handshake will do. And you just have to use your own instinct and common sense.

But it’s more than instincts. It’s emotion.

It’s a combination of instinct and emotion. There’s a lot of emotion in instinct.

Tell me about that speech in Sale, in Victoria.

Oh, the address where I worse the bullet proof jacket.

Why did you do that?

The commonwealth police told me that the local police had spoken to somebody who’d rung up and wandered into the local police station and said, “I’m going to shoot the so-and-so when he comes to this rally.” They thought it was genuine and they said, “You ought to wear this.” I didn’t want to, and then Grahame Morris said what am I going to say to Janette if you get shot? I foolishly in my view ... it was my responsibility and nobody else’s. I wore it, and I felt afterwards that I shouldn’t have.

Did you feel stupid?

I did. I felt quite stupid and it was stupid because I never actually felt frightened. I never felt frightened at any meetings I attended in that whole gun thing or indeed generally ... I mean, there were some violent meetings I went to, but Australians are not violent people.

Strangely enough, Ricky Muir, the current senator, was in the audience that day. It was his first experience of politics. He saw you and thought, “Relax mate, you’re in the country,” because he could see you wearing that vest.

Well, he was right and I was wrong. I didn’t know that (that Muir had been there).

Did you get angry with yourself?

I got very angry with myself.

What does John Howard do when he gets angry with himself?

I just … what do I do? I just resolve never to make that mistake again and to tell people immediately around me I’m not going to make that mistake again.

What did it say? That you didn’t trust Australians?

Yes, and I did. Otherwise I wouldn’t have gone to the meeting in the first place.

What did Pauline Hanson’s success say about the two political parties?

I think what Pauline Hanson’s success said and what Clive Palmer’s success has said so far is that the two political parties now have fewer rusted on supporters. There’s a sort of a detachable 10 per cent flank on either side of politics that can be seduced away for a period of time.

The test of course for Pauline Hanson was that in the end she had no lasting solutions to the country’s problems. When she was actually pressed to articulate an economic philosophy it made no sense what came forth and I suspect that will be the case with Clive Palmer. One thing I wasn’t willing to do with Pauline Hanson was to call everybody who voted for her a racist. Some people, including some in my own party, were in effect urging me to do.

Was she a racist?

I don’t think she was a racist. I thought she had some bigoted views and I didn’t think the people who voted for her were racists. Some of them were, I mean, there are some racists in Australia, don’t get me wrong; and there are bigoted, prejudiced, racist people in Australia, but the great bulk of the Australian community is not racist. The people who were attracted to Pauline Hanson were in the main people who felt that life had treated them poorly or they were unhappy with the denigration with our traditional past. A lot of people who voted for Pauline Hanson were people who rejected the Keating prescription on reconciliation and the republic and the flag and all of that. They felt that, you know, she stood up for traditional Australia. She was the battling outsider to a lot of people. The fact that she wasn’t as articulate as some of her slick public relations presenters wanted her added to her appeal. She struck a chord with that group of the Australian community. We’d gone through a lot of economic change, and some people did feel they’d missed out ... I got a lot of criticism. A lot of people in my own party said, “You’re not attacking her hard enough.”

What did they want you to do?

They wanted me to launch an all-out attack on her and (the) people who supported her. I couldn’t see the sense of that. I thought that would prolong her popularity.

But you did come out strongly seven or eight months later. Why did you wait that long?

I waited that long for the very simple reason that I’ve just explained to you … I felt to have gone out all guns blazing at the very beginning would have only enhanced her popularity.

Were critics satisfied?

No, I don’t think my critics were ever satisfied on that issue. But I felt ... as things finally turned out, the strategy I had adopted was the correct one.

A few months after you became prime minister you had to deal with a personal trauma when your wife Janette learned that she had cancer. Tell me how you found out about that.

She told me in my office she’d had a test and revealed that she very likely had cervical cancer. We then went off to a meeting and understandably neither she nor I were very focused on the meeting so the next couple of weeks were just tumultuous in an emotional sense because I feared for her and she obviously feared for the future. We worried about the possible impact of a prolonged illness or something even worse on our children.

Did it look like that did …

Well, anything that involves (cancer) is always a possibility. Anyway, we had all sorts of additional tests. Well, she did. I was naturally with her as much as was humanly possible. It was a terrible time but thank God ... that she had a wonderful surgeon and terrific medical staff at King George V hospital in Sydney, and after a major operation she had a long recovery period. But she did recover and we’re very blessed for that reason. That was in 1996 and she was very strong and stoic and kept saying, “Well you’ve got things to do and you’ve got to keep working.”

You said once that you had been immobilised for days when you heard about that.

Yeah, I was ... it really did affect me quite badly.

What were you thinking of?

Well, I was thinking that I might lose my wife. I was frightened that it would, you know, be the worst possible outcome and it might claim her life.

Paul Keating rang you during that trauma.

Yes, he did, and it was very gracious of him. He rang me and said he’d heard about it and said, “I’m very sorry to hear it, and it’s tough ... You’ve been through a lot this year and then this happens ... I hope everything’s all right.” I thought it was a very decent, gracious thing for him to do, and I thanked him for it and I acknowledged it.

Those first couple of years were really a roller-coaster for you.

We did an enormous amount.

Did you have a sense that you were not going to waste your time as prime minister?

I felt very strongly that having got there against all previous expectation, I didn’t want to lose a moment. There was a feeling that the previous coalition government had not fulfilled everything in its mandate or perhaps it disappointed people. The public will cut the new government a certain amount of slack, providing it does something. It won’t put up with a multitude of mistakes. It won’t put up with a multitude of backflips and reversals. It’ll put up with you doing things that it may not totally endorse if you do it with conviction. They believe it’s probably in the long-term interest of the country. They knew we had to do something.

But you had to break a couple of promises when you came in, didn’t you?

There were some things we had to go back on. We couldn’t deliver everything but people felt we were essentially the government that we promised we would be.

How much of these early decisions were John Howard’s decisions?

There was never any bypassing of the cabinet process. One of the things I resolved to do was to treat the cabinet process seriously, and that meant you didn’t ambush a cabinet by announcing things before they met; that’s a recipe for disaster. But equally you don’t have the cabinet meeting all day and all night; that’s also a recipe not only for disaster but also fatigue and very bad decision-making.

You’ve described 1997 as your worst year apart form 2007. Why?

Well, 1997 was a year in which I think people sensed that after a fantastic start we’d started to drift. And people saw a government being indecisive and drifting. People started jumping up and saying, “We’ve got to do this, we’ve got to do that.” We started to look a bit scratchy.

Did later MPs get up in parliament and put one finger up to suggest that you were a one-term prime minister?

I’m sure they did. I’m sure they devoutly hoped I was a one-term.

Did you think you might be a one-term prime minister?

I always think you might be.

So it crossed your mind.

Oh, yes.

Is that self-doubt creeping in there?

Well, if it is, I plead guilty to it. But I tell you what, it’s common sense to think that you might lose the next election if you don’t lift your game.

How did you lift your game?

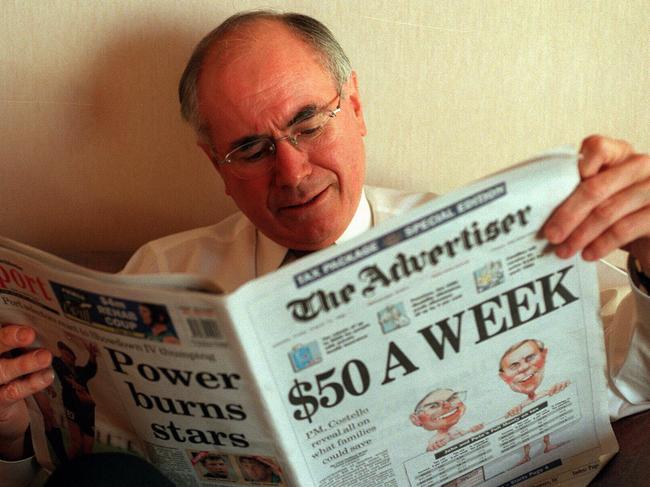

One of the ways I lifted my game was to decide to spend an enormous amount of my time — a lot more of my time — on talkback radio as a way of bypassing the Canberra press gallery. Not that I don’t love the Canberra press gallery but I felt that if I talked directly to people — and the best way to talk directly to people in Australia is talkback radio — talkback radio has a greater influence on politics in Australia than any comparable country. I got pneumonia in July or August or something in 97, and I was in the Mater Hospital in Sydney for a week recuperating (and) at Kirribilli for two or three weeks afterwards, and I thought during that period of time we had to resurrect indirect tax reform. In other words, that was the birth of the what ultimately became the GST.

So you’re delirious from drugs ... you’re in hospital, and you’re thinking of the GST.

I’d started to think about it before I went into hospital and it was a time to reflect and think. When I came back I called a meeting of cabinet and said, “I think we’ve got to start this … I’d ruled it out in previous elections, I know I said ‘never ever’, I’d gone overboard in my denial.”

Can we ever believe politicians?

I think you can if the prime minister who says “never ever” then says, “I’ve changed my mind, I’ll put it to you at an election and you can throw me out if you don’t accept the change of mind.”

You took the centre stage when you were launching the GST. did you ever get the wobbles over it?

I never got the wobbles over the GST.

Over the rate?

Over the rate … well … there’s a celebrated reference in Peter’s book to the fact that at one stage late in the preparation I asked him to have a look at the possibility of having a lower rate in return for something else and he had a look at it and he came back and he said, “I don’t think that’ll work for the following reasons.” I said OK. I didn’t think that represented the wobbles.

Well, he puts a bit more colour on it. He said he was seething with anger.

He shouldn’t have been because I was just asking him to have a look at something. Prime ministers always do that of treasurers, and they have every right to.

It was an incredibly courageous thing to do. No other western democracy had taken the GST to an election. Business leaders or media owners such as Kerry Packer rang up and told you you were crackers.

He rang me up one Sunday night at Kirribilli House and he said, “Sport, you’re not ‘blank’ thinking of ‘blank’ introducing a GST, are you?” I said yes. He said, “You’re crazy. You’re mad. The mob will not thank you for that. Just give them tax cuts.” I said, “We’ve got to fund them.” We had a spirited discussion. He thought I was wrong, and he said so in no uncertain terms.

Why did you decide that Australia should support the independence of East Timor?

Because I came to the conclusion that the continuation of our previous position of support for Indonesian sovereignty was no longer sustainable in the wider world. The more I reflected on it the more convinced I became that it wasn’t going to last because Suharto’s grip on power was loosened by the Asian financial crisis, whereas in 1995-96 people still thought Suharto would go on forever. I think I probably still thought his position was solid when I first went there late in 1996, but by 1998 with the impact of the global financial crisis, and of course earlier that year he’d been replaced by Habibi. So for those combination of reasons we decided after the 1998 election to change our policy (which) led to the letter that I wrote to Habibi suggesting that he hold some kind of inquiry and plebiscite about different attitudes as to how East Timor should be governed. And I remember at the time after we’d taken that decision Alexander Downer tapped me on the shoulder. He said, “John, this is a really big decision,” and it was. We were reversing 25 years of bipartisan policy. It wasn’t just the Labor Party, it was the coalition as well.

Did you realise how big it was?

We didn’t expect Habibi to go further than I had suggested.

Does that mean there was a miscalculation that you were so surprised by president Habibi’s response?

Some people would say it was a miscalculation but it was a miscalculation further along the road that we already started to tread.

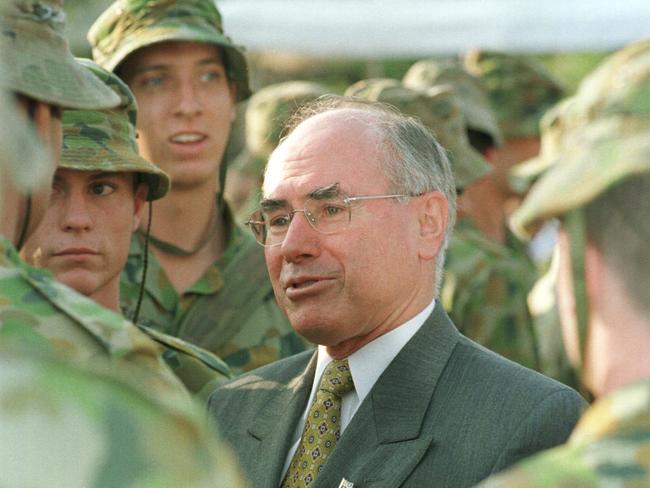

At what point did you realise that you would be sending troops into a potential conflict zone?

I realised that we would be sending troops into a conflict zone after the mayhem that seemed to break out in East Timor when the referendum voted overwhelmingly for an independent East Timor because rogue elements of the Indonesian military had broken loose and basically wrecked the place. A lot of people’s lives were in danger and I knew then that we would have to send a peacekeeping force in. I was determined that Australia would lead the peacekeeping force.

Why was that?

Because this was right on our doorstep. I felt that we did have to take the lead because we played a major role in bringing about the shift in policy. We knew we had to get the United Nations involved because we wanted to have a general benediction from the UN if at all possible, and they did.

Many people were telling you to go in without that consent.

Oh, I can remember people were yelling at me on the phone (on) talkback radio, saying, “You’ve got to go in, don’t wait.” I said, “Well, I can’t. It’d be invading a country.”

That would have been war.

That would have been war — war with Indonesia. Not very smart. So we resisted that but in the end the Indonesians agreed. They were very unhappy about it because it was humiliating, but it was the right outcome.

Did you expect casualties?

Oh yeah. I feared there would be, of course I did. You always expect casualties when you have military operations. I remember the night before they left, Janette and I went to the Lavarack Barracks in Townsville and had dinner with the lot of them. As we walked out of the dinner, it was one of those balmy North Queensland evenings, you could see NCOs with groups of soldiers, talking to them very quietly. I thought to myself, “My God, some of these fellows could get killed tomorrow.” That is the impact that thing has. Now, fortunately, that didn’t happen and I give enormous credit to general Peter Cosgrove, our Governor-General. He was then the commander ... and he had gone to East Timor to meet his Indonesian opposite number and to sit down with him and say, you know, let’s make sure that this all works okay and nobody gets hurt. I remember a few weeks later I went there in an open-door helicopter, flying over the city of Dili and you saw the wreckage.

When you decide to send troops into a conflict zone where you expect casualties, do you think of your father and your grandfather at a time like that?

I suppose I did on occasions but I, obviously never ever forgetting them, you think more immediately of the young men you’ve just seen. I remember that night in Townsville I walked past these young fellas and I thought, “Gee, they’re all so young.”

Did they talk to you?

I talked to them earlier in the mess hall and they were so buoyant and looking forward to it.

They were looking forward to going?

People join the army to do something, most of them do. I remember in the whole East Timor time I only had one complaint and that was from a bloke in Darwin who complained that he didn’t get sent. That’s typical, I suppose, of a generation that hasn’t gone through a war with mass casualties and the like. But we should be very grateful that there are people in our country who want to go to war when necessary. We should never have them in anything but the highest regard and respect. You need men and women who are willing to do that, and we should be grateful that they exist.

When you rang president Bill Clinton and asked for help, what was his initial response?

He said, “I can’t provide you with any troops, can’t provide you with any boots on the ground.” He said the American military is incredibly stretched. I was quite amazed at his reaction. I was pretty unhappy, and he sensed that. Then a couple of days later Alexander Downer, bless him, went on CNN and really was very critical.

He gave it to the Americans.

He was very critical of the Americans, and both of us had basically said, me privately and Alexander publicly, “Listen, whenever you’ve wanted assistance and an ally we’ve been there and now we want a bit of assistance and you’re not going to be there.” And then they really got the message. All in all in the end they were very helpful and I have to say that Bill Clinton and I developed out of that a very good relationship.

What did the liberation of East Timor say about John Howard as prime minister and about Australia more generally?

I think liberation of East Timor did enormous credit for Australia. We did something that Australians felt good about.

In early 2001, dark clouds once again started to appear on the horizon to the point where there was a headline that said, “John Howard needs a miracle.” Do you remember that?

Oh, I do remember that, yeah. I was doing badly.

And then on the 26th of August, Norwegian freighter MV Tampa appeared on the horizon and picked up, I think, 434 asylum seekers. When did you hear about that?

I remember at that time I had a discussion with Philip Ruddock, who was the immigration minister, and we had a meeting of the national security committee of cabinet, one was scheduled and then there was a full cabinet meeting. We pretty quickly decided that we just had to put our hand up and say, “No, you cannot come to this country.” It was a very dramatic thing ... They were picked up in the Indonesian search and rescue area, and under the international protocols they should have been returned to the Indonesian port from whence they had come. And so therefore the idea that in some way we were violating international law and the way we subsequently behave, that was nonsense.

But the pressure was on.

Oh well, the pressure was on. I had been arguing right up until then that what we had been doing was the best that could be done under the circumstances. But the public was getting increasingly angry. They felt we were losing control of our borders.

Were we?

That was the impression people were getting, and if we had allowed these 426 people to effectively hijack that Norwegian vessel and compel the master of the ship to take it to Australian borders and for them to land in Australia or in Australian territory, people would have said, “You have lost control of your borders.” Our SAS boarded them and took it over and ultimately the asylum seekers were transferred to Nauru and dealt with in the offshore processing fashion. We implemented what we call the Pacific solution and it stopped the boats coming.

Who came up with the Pacific solution policy?

A combination of people: my officials, my office, Philip Ruddock.

How much of it was you instinctively knowing what to do?

Well, of course a lot of it was, but I never want to play down the contribution of others. This was something where I had a lot of support as people instinctively knew also that it was the right thing to do, and if we had allowed more than 400 to come to Australia and they had been able to achieve their objective, it would have sent a terrible signal. The fact is by the end of the year the boats had stopped and they remained stopped until 2008, when Kevin Rudd foolishly reversed our successful policy.

When you were criticised for not having compassion because it was a hard policy, did it ever rankle with you?

It annoyed me because it was so wrong.

Why was it wrong?

It was wrong because for every asylum seeker who got through the net unless we were willing to increase the overall intake of refugees, that asylum seeker knocked out of the queue somebody who may have waited years in a refugee camp in Indonesia to be admitted into Australia. There’s a limit to how many people Australia can take as refugees.

When we control our borders, what is the upside of that for immigration?

Well the upside of that for immigration is that public support for immigration rises.

And it did ...

It did ... I mean, we had very high levels of immigration when I was prime minister. I believe in immigration. I think post World War II immigration in Australia has been something that has brought multiple benefits to our country. The public only gets hostile to immigration if they think it’s uncontrolled.

With mandatory detention you were winning the political contest, but did you ever think that the human cost was a very very high one?

Look I never liked to see people in detention but I even like less the sight of people drowning at sea. And the pre-Tampa policy resulted in that. It happened after Rudd foolishly undid my policy. People talk about the razor wire and talk about people being behind it and children being behind it; yeah, I feel that too. But the alternative is so often people drowning at sea.

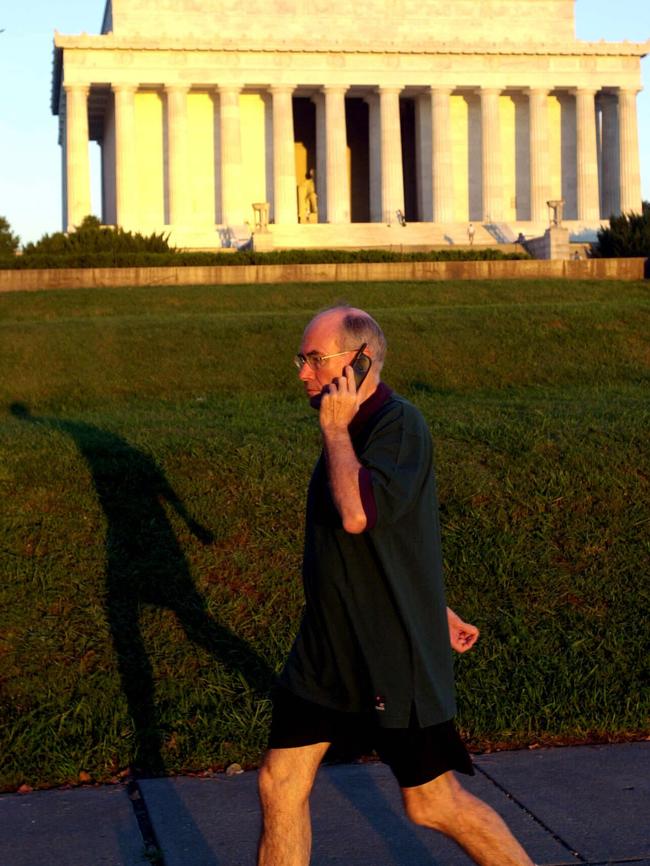

You were in Washington on September 11th 2001. Tell me how that day unfolded.

It was extraordinary. I started off a beautiful day. I went for a walk. I then got ready to have a news conference and before I left my hotel room to go to the conference Tony O’Leary, my press secretary, came around to brief me on what the journos were going to ask; in the course of it he said, “By the way, boss, a plane has hit one of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre,” and we both said, “Well, that’s a bad accident.” A few minutes later he came running back and saying, “Another plane has hit the other tower.” And we knew that it hadn’t been any accident and we flicked on the television ...

What’s going through your head when you ...

The only thing going through my head was trying to assimilate what it meant, who was responsible. I didn’t at that stage know it was al-Qaeda-inspired terrorists. I knew that some act of terrorism had occurred but I didn’t know how sinister it was. It was during my press conference that the third plane hit the Pentagon. We’d drawn the curtains for the television cameras and after it was over, the security police had had the little things in their ears said they’d picked it up the explosion ... and we pulled back the curtains and we could see the smoke billowing out from the Pentagon.

And how are you feeling when you see that?

I immediately thought of Janette and Tim — Tim our son was in London at the time. He’d come over to Washington to see us, and he and Janette had set out earlier for some sightseeing and were heading for the Jefferson Memorial, which is on the banks of Potomac River, not far from the Pentagon. So I was saying, “Where’s Janette?” and they said, “Oh don’t worry, Frank’s with her.” Frank was one of my AFP blokes and he could look after himself and a lot of other people at the same time. I felt that was OK. Then I went down, turned on the television set and talked to staff and within a short period of time the head of my American security detail came into the room and said, “You’re out of here, prime minister. I haven’t lost anybody yet and today’s not gonna change that.” So I went off and we were taken to a bunker ... it was essentially a bunker ... downstairs area of the Australian embassy in Washington. That rapidly filled with Australians, and before long Tim and Janette turned up. Then I had a news conference. I composed a letter to President Bush so it was there that I had done so immediately because I had spent a lot of time with him the day before. And the possibility of a terrorist (attack) just hadn’t come up. I mean al-Qaeda was not mentioned.

So you had no intelligence.

No. I didn’t have any and he didn’t have any.

And you’d only met George Bush the day before.

I had met him for the very first time the day before.

As you’re driving through the streets of Washington, was there panic on the streets?

No, there was no panic on the streets, of course there wasn’t. I didn’t see any panic on the streets. I thought everybody associated with it whom I came into contact was remarkably calm and deliberate, but there must have been a fair bit of panic in New York as everybody saw on the television, and of course the television was so graphic. We were glued to it and nobody can ever forget the sight of those towers collapsing and the fear that thousands of people were going to die.

Including Australians.

Including 20 Australians.

Nothing can ever prepare you for an event like September 11. How did you see the world change after that?

This was a completely unprovoked, audacious, outrageously successful terrorist attack. This was a greater violation of the American homeland than Pearl Harbour. The terrorists had destroyed the World Trade Centre. They’d taken out the Pentagon, and if those brave people on that other aircraft that crashed in Pennsylvania had not been so brave, they probably would have taken out either the White House or the Capital building, so it was outrageous. It was audacious. It was successful and it was completely unprovoked. That doesn’t change the paradigm of the world in which we live. Nothing will.

Did you fear for Australia?

Of course I feared, and a lot of us did, that we were going to have a chain reaction. Washington then New York then London then Paris then Tokyo, perhaps Sydney, then Melbourne — who knows? You’ve got to remember that nobody was prepared for this and naturally fear and imagination runs riot. And I made it very clear Australians would stand should to shoulder with the Americans in the fight against terrorism.

You knew that America would retaliate.

I knew America would retaliate.

And you signed Australia up for ...

And I did sign Australia up to support America in her retaliation.

What did you think that meant?

I assumed that that would mean the provision of some forces. Within a couple of days it became apparent that intelligence services in America and elsewhere suspected that it had been organised by al-Qaeda out of Afghanistan and we were provided with very solid proof.

So that commitment that you made in Washington was a strong one, it was an open-ended one. You didn’t know where it might lead us because the Americans hadn’t decided where it would lead them.

No. But I made the calculation that their retaliation would not be indiscriminate and improperly based, and I was right.

Did you know that it would take us to Iraq?

No, I didn’t. The two were separate decisions. I did know from discussions I had with Michael Thawley, who was our ambassador in the US and previously had been my international adviser, that Iraq would be … as a result that what had happened, would be back on the table for the Americans.

But when you gave that open-ended commitment, the Americans would have been entitled to think that you would be joining forces in Afghanistan or whether it came to Iraq ...

No, I don’t think they would have, and I’m sure they weren’t. And nothing in the discussions I subsequently had with president Bush or the secretary of state Colin Powell or with Condoleezza Rice, or Rumsfeld suggested I did, they were two separate but related issues.

What changed after September 11 in relation to their position on Iraq?

I think what changed was a growing belief that one possible outcome of leaving Saddam in possession of what they believed to be weapons of mass destruction at stock piles was that he might hand them to some rogue elements, the terrorists who would use them with lethal effect against the US or against other countries. That was one of the principle reasons why they embarked upon the operation in Iraq.

The federal election in 2001 was very much a national security election, wasn’t it?

Yes, I’d say national security in 2001 shared equal billing with economic management.

And you had become very much the national security leader.

I had, that’s true. There’s no doubt that the perceived strength that we had in that area helped the government in that election. I still believe we would have won that election if Tampa had not occurred and If September 11 had not occurred, and Afghanistan had not occurred ... We all wish that Afghanistan had not been necessary. I still believe we would have won.

This is a transcript of the series originally recorded in 2014 for Sunday Night on Channel Seven, and broadcast in full on Sky News in January 2015.

Howard Defined will be broadcast at 8pm each night from Sunday January 11 to Thursday January 15, on Sky News, ch 601. For more transcripts, see theaustralian.com.au/features immediately after each episode.