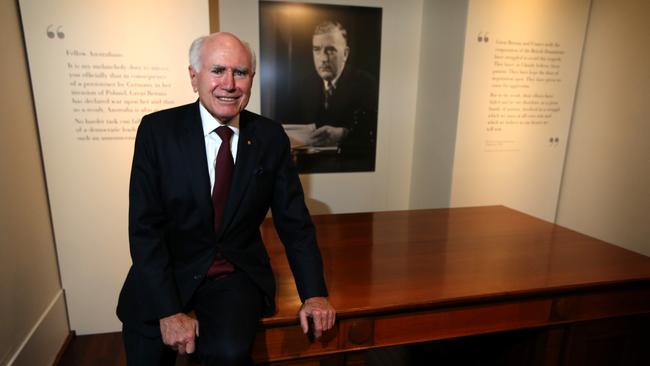

John Howard explains how Bob Menzies shaped modern Australia

MODERN Australia is in many ways a tribute to Robert Menzies’ clear vision, writes John Howard in this exclusive book extract.

I CLEARLY remember election day December 10, 1949. My parents voted in the early evening — polling booths stayed open until 8pm then — at Earlwood Public School in Sydney, where I had just completed fourth class.

After voting, Mum and Dad, with one of my older brothers, Bob, and me in tow, went to the local picture theatre, the Mayfair. As was the custom, we saw two full-length feature films, this time Command Decision, an American World War II movie starring Clark Gable and Walter Pidgeon, and Strange Bargain, a tale of a suicide made to look (rather clumsily) like a murder for insurance purposes. American war films proliferated at that time.

They had been produced for the massive home market, and they naturally created the impression that the US had won the war almost single-handedly. During the screening of the second film, a slide appeared on the screen, saying simply, “L-CP takes early poll lead”. When we arrived home, we found my eldest brother, Wal, who had cast his first federal election vote that day, sitting on the floor beside our large radio in the dining room. He said, “Menzies is in. The biggest swing has been in Queensland.’”

The Menzies to whom he referred was Robert Gordon Menzies, leader of the Liberal Party of Australia. He would serve as prime minister of Australia from December 1949 until January 1966, holding that post longer than anyone else. My family was very happy with the outcome.

Few of those who voted that day would have given much consideration to how long the victorious party leader might remain in office. The thoughts of most of them, especially those who had just shifted their support to the Coalition, would have turned to what his opponent, outgoing Labor prime minister Joseph Benedict Chifley, once famously identified as the most sensitive part of the political anatomy, “the hip-pocket nerve” — a wonderful metaphor for living standards.

The election took place four years clear of World War II. The Australian people were increasingly focused on the employment, growth and family opportunities that might come their way after the suffering, drudgery and restrictions of wartime. There was a growing feeling that the ruling Labor government had maintained wartime controls, such as petrol rationing, too long after the war ended.

This was certainly the view of my parents, Lyall and Mona Howard. But then, they were unreliable witnesses: my father owned a service station, and he and my mother were both rusted-on Liberals. Lyall was more of a Menzies man than was Mona, however — on occasion she thought the soon-to-be PM was too “full of himself” and could become “a bit of a dictator if he got the chance”. She would ignore his plea for a “yes” vote in a referendum to ban the Communist Party two years later.

There was a sense of anticipation, even excitement, in the Howard household in the days that followed the election. My parents felt that something new had come and that our country’s future would be better.

No one — including, I am sure, Bob Menzies himself — imagined that he would remain prime minister for 16 years and in the process reshape our nation.

THE Australia that I grew up in was stable and full of hope. It had blemishes and shortcomings, but probably fewer than other comparable societies. Robert Menzies embodied the sense of security and optimism that was a hallmark of that era.

Features of those years no doubt seem strange and unfamiliar to later generations — most importantly because they pre-date the social and cultural upheavals of the 1960s. Yet our lives have not changed so much that it isn’t possible to identify connecting threads in attitudes and policies.

I have acknowledged the similar approaches of the Coalition and the ALP towards certain micro-economic issues, such as industry protection and centralised wage fixing. However, there was nothing bipartisan about their respective attitudes towards the possible nationalisation of the private banks in 1948.

If that openly socialist policy of the Chifley Labor government had been successfully implemented, then the economic history of Australia since 1945 would have been fundamentally different.

Success in grabbing the banks would have encouraged further excursions into nationalisation by that government. Australia might then have followed the dismal British path following World War II of an ever expanding and inefficient state sector, which culminated in the economic paralyses of the late 70s, and which only the force of Margaret Thatcher could overcome.

One way to assess the lasting impact of the Menzies years is to ask the simple question: what self-evident strengths of modern Australia are due to the actions of governments of the Menzies era?

In answer, first, there is Australia’s place in the world. In 2014 Australians see their country as an integral part of the Western world, with our security firmly anchored in the Australia-US alliance. This alliance was cemented more than 60 years ago, in the first two years of the Menzies government, following the signing of the ANZUS Treaty on September 1, 1951.

More than that, Menzies, in his decisions and actions as prime minister, was faithful to the spirit as well as the letter of that alliance.

Today Australians see both their present and future prosperity as closely linked to the stunning economic growth of Asia. Australians know that China’s voracious demand for our resources was one of the principal reasons why our nation largely escaped the impact of the global financial crisis.

China might have been the economic saviour in 2008 and the years immediately following, but it was Japan that first provided the trading gateway into Asia in 1957. The commerce agreement of that year between our two nations was forged despite the hostility of the Labor Party and the profound misgivings of many Australians. Only 12 years had passed since the end of World War II. There were still painful memories of Japanese brutality towards Australian prisoners of war.

This historic agreement meant that from then on Asia would increasingly be seen by Australians as a region of opportunity and growth, not of unfamiliarity or even hostility. Unlike the ALP of that era, Menzies saw the long-term benefit to Australia of close relations with both Malaysia and Singapore. He secured this through the provision of military assistance to help defeat the communist insurgency in the Federation of Malaya, and in resisting Indonesia’s unjustified confrontation of Malaysia in the 1960s.

Contemporary relationships between Australia and Asian nations are everywhere to be seen, and not least in the cultural vibrancy of Australian citizens of Asian heritage. The birth of those relationships can be traced to the Colombo Plan, inaugurated in the early months of the Menzies government. Its legacy continues to enrich our links with our Asian neighbours.

Post-World War II migration has brought numerous benefits to Australia. Labor’s Arthur Calwell started it; Menzies expanded it; and it was Harold Holt who brought the White Australia policy to a close.

Since the end of World War II, Australia has had two long periods of economic growth. The first of those was from the late 40s through to the early 70s: the time span of the Menzies era.

Consistent growth, low unemployment, rising home ownership and an egalitarian enjoyment of the fruits of economic success were features of Menzies’ years as PM. The great Australian middle class emerged during that time. Preserving it remains a constant national aspiration.

Australian politics today is less tribal than it was during the Menzies era. As a young political activist I assumed the existence of what could be called the 40-40-20 rule — that is, 40 per cent of the electorate would always vote for the Coalition and 40 per cent for the Labor Party; the remaining 20 per cent would move between the two. It is not too much of an exaggeration to say that such has been the dilution of rusted-on party allegiances that we are now closer to a 30-30-40 rule, with a much greater proportion of the electorate disposed to give their support to the minor parties. The primary vote for the ALP in the House of Representatives at the 2013 election was 33.4 per cent. Such a low figure would have been unheard of in Menzies’ day.

The ALP’s worst result during that time was in 1966, when its primary vote was 40 per cent. And this was notwithstanding the fact that the Democratic Labor Party, which had splintered from Labor at the time of the 1955 split, was still a political force in 1966.

The emergence of minor parties has not been the only explanation for the decline in direct support for the Coalition and the ALP. There is now a much greater propensity for Australians to shift between the major parties from one election to the next.

Since the collapse of Soviet communism, the old Left–Right divide, in part a projection of the ideological contest between the Soviet bloc and the West, has been increasingly replaced by differences on environmental matters as well as on so-called socially progressive issues.

This process was only beginning when the Whitlam government came to office but has gathered pace since. In recent years it has placed a particular strain on the ALP, as it has exposed sharp divisions of opinion between its traditional blue-collar worker base, often quite socially conservative, and the new, inner-urban, tertiary-educated class that inhabits the socially progressive wing of the Labor Party.

The biggest demographic shift of voters in Australia during the past 50 years has been among Catholics, and this commenced under Menzies. In 1949 the great bulk of Catholics voted Labor; by the early 60s, significantly aided by Menzies’ approach to state aid for independent schools, as well as the social mobility of the Menzies era, this was changing in a quite significant way.

The consequences were long-lasting. It was estimated that at the 1996 election which brought my government to power, for the first time ever a majority of Catholics voted for the Coalition.

The description of someone as a “conviction politician” did not exist in Menzies’ time. It has been used in the modern era to describe someone who is not driven wholly by focus groups, public relations considerations and an almost desperate search for a stance on an issue that offends no one. It describes a person who has a clear set of principles and beliefs, and is unafraid to express them.

Menzies was a conviction politician. His beliefs were clear. It was never difficult to know where he stood on an issue, all the more so when his position was unpopular.

As a consequence, he transmitted strength and dependability. Menzies’ peerless political skills delivered him years of power, which enabled him to govern according to his values and beliefs.

He understood the simple truism that political power without purpose is pointless, and that the most ambitious policy agenda in the world is worthless without political power.

He was superb as an aggressive political campaigner, but at the same time, in office he always knew what he wanted to achieve. He had an intrinsic understanding of the fact that the first requirement of a political leader is to stand for something.

The Liberal Party’s founder brought massive natural talents to public life, not the least of which was a first-class intellect. Robert Menzies was the finest political orator I have ever heard. He was blessed with a rich, strong voice; the accent was educated but in no way affected or pretentious. It was distinctively Australian.

When speaking, his timing was impeccable. He had a legendary capacity to score off interjections, either in a vast auditorium or in the House of Representatives.

Our longest serving prime minister had remarkable resilience. A lesser person would have been weakened and diminished, if not broken, by the indignities that were heaped upon him by some treacherous colleagues. Instead those experiences strengthened and informed him. He learned from his mistakes and past travails.

Robert Gordon Menzies not only created the most successful political party Australia has yet seen, but he also dominated Australian national life for a generation like none before him or since. In the process he helped fashion the fundamental characteristics of modern Australia.

This is an edited extract from The Menzies Era by John Howard (HarperCollins, $59.99), out on Monday.