Israel warns Iran: leave Syria

Israel is prepared to defend itself against the “half-crazed lunatics’’ in Tehran.

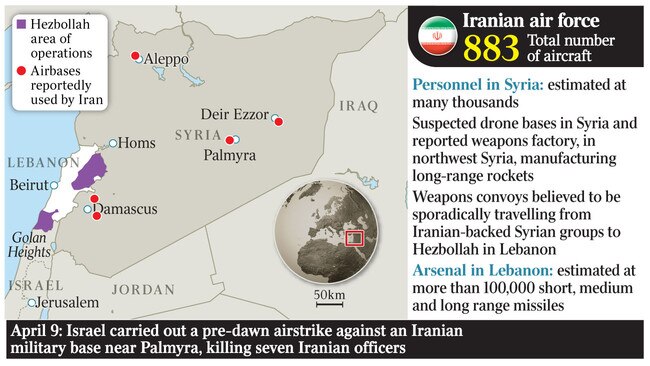

One of Israel’s most senior diplomats has laid down the gauntlet, suggesting the Middle East could be months away from major conflict if Iran persists in maintaining military bases in Syria.

In a sit-down interview with The Australian to mark the country’s 70th anniversary, Israel’s new ambassador to Australia, Mark Sofer, doesn’t mince words, dwelling on Israel’s grave concerns about the insidious beachhead of Iranian military power pushing into Syria, which shares a border with Israel.

“Iran cannot stay in Syria, period. We’re not going to have them on the border. It has passed what we are going to be able to accept under any circumstances,” he says, adding Iran is “crossing a red line”.

“Our position is clear, they have to get out and go home,” Sofer says.

In an interview conducted against a backdrop of escalating tensions in the Middle East following US, British and French airstrikes against Syrian bases, Sofer says he doesn’t want to talk about any timetable for retaliation, simply stressing “the principle of permanent Iranian presence inside of Syria will not be condoned by us under any circumstances”.

Tight security at the Israeli embassy itself is a reminder how, 70 years since its creation, the security of the only genuine example of liberal democracy in a region not known for its tolerance is far from guaranteed.

Highly articulate — and for a career diplomat refreshingly frank and talkative — the new Israeli ambassador to Australia says he’s happy to be here, having been responsible previously for Israel’s relations in the Asia-Pacific, from India to New Zealand.

“I’m a bit of an Asia hand. I could have basically chosen a lot of places but I chose here. This is seen as a very important posting, one of the more important postings we have,” Sofer stresses, underlining the strong political, economic and defence relationship with Australia — not to mention the “very good and able”, large Jewish community.

Sofer, married with three adult daughters, took up his post in November last year. He takes a dim view of an increasingly farcical UN. “Syria has just been appointed chair of the UN forum on disarmament of chemical weapons. But it has just used them!”

The effectiveness of the latest bombings of Syria has divided expert opinion. The US also bombed Syria in April last year. Sofer, who seems to welcome the Trump administration’s tough approach, says the strikes have “sent a strong message” to President Bashar al-Assad. “(But) I think Iran will not be dissuaded by that,” he says.

Israel released pictures of Iranian bases in Syria just days ago, after revealing the Iranian military drone shot down over Israel’s airspace in February had been armed with missiles.

“The Iranians are sitting there, threatening our existence using military means, even before I enter into their nuclear ambitions, even before I enter into their outrageous anti-Semitism,” Sofer says.

He paints a picture of a Middle East increasingly influenced by an Iranian government so belligerent that even Arab nations — former enemies of Israel — are looking to Israel to help contain it. “Until recently what you saw was every time something bad happened everyone got up on hind legs and said ‘Israel is to blame’,” he says. “But I think there’s a growing realisation that the Middle East is faced with large challenges and Israel is part of the solution and in their eyes not the problem,” he adds, pointing to improving relations with Egypt, Jordan and the United Arab Emirates.

The country is more than pulling its weight in humanitarian terms. “We’re accepting into Israel a huge amount of Syrian wounded into our hospitals. We don’t make a song and dance about it,” he says, referring to tens of thousands of Syrians being treated for wounds in the north of the country. In the conflict over the past seven years, more than 500,000 Syrians have died.

Sofer is at pains to draw a distinction between the Iranian people — “very erudite” — and the “half-crazed lunatics” running the theocracy in Tehran. “We’re talking here of a country which more than any other is bringing about a destabilisation of the Middle East and wider afield,” he says.

The ambassador displays his nation’s famously coy attitude to its own military capabilities.

“We’re not a nuclear power. We have always said so, and will always say so,” he says when asked about his country’s nuclear development. Try finding a source that argues Israel doesn’t have a sizeable battery of nuclear weapons. Can anyone blame Israel, though?

While noting Assad’s use of chemical weapons is “abominable”, the ambassador says Israel has a more nuanced view on the Russian-backed regime.

“A lot of questions could be asked, what would be the case if the Russian army weren’t there and we had only the Syrians, the Iranians and the Hezbollah running amok?” Israel is home to more than one million ethnic Russians.

Russia’s reputation in Australia and the US has been severely tarnished in the wake of reported attempts to influence the US election and, more recently, to assassinate enemies of the regime in London.

But Sofer says Israel has “good relations” with Russia “on a number of levels”.

“Right now the Russian army is on our borders, which isn’t the same as the Iranian army on our borders, because one is good and one is awful,” he explains.

Turning to his experience of Australia, Sofer lauds Australians’ tolerance and welcoming attitude, especially to Jewish people. “Honestly, I’ve been 36 years in foreign service, lived all over the world from Latin America to Europe and Asia, and I can tell you this is one of, if not the most tolerant society I’ve been in,” he says. “It’s not by accident the Jewish community has done so well here,” noting how few Australians seem to care who is or isn’t Jewish — historically an obsession in Europe and even North America.

“People don’t know Monash was Jewish and for those that do, it makes absolutely zero difference to them,” he adds, referring to the World War I military hero.

Geopolitics overshadows interview time to discuss Israel’s economic growth. In a sense the Japanese of the Middle East, Israelis have built a rich, advanced economy with few natural resources. With few nearby trade partners until recently, the country has been forced to innovate. Unlike the Arab states blessed with oil, Israel, like Japan, has had to rely on the ingenuity of its people to obtain a level of income per person almost double that of oil-rich Saudi Arabia.

“Until recently we had no natural resources worth talking about, a bit of potash, that was about it. We discovered gas in the last few years,” Sofer says.

Since 2009 Israel has discovered gas off its Mediterranean coast, enough to meet domestic needs for 40 years.

The ever-present threat of war hasn’t weighed on the country’s development.

Its population is growing rapidly — at almost 2 per cent a year, much faster than Australia’s — but its economy is growing faster again. During the past decade Israel’s gross domestic product per person has increased twice as fast as Australia’s. The International Monetary Fund forecasts Israel’s economy will grow 3.4 per cent this year. Inflation is around zero and the unemployment rate is just above 4 per cent.

Its success hasn’t been accidental, involving deliberate government policies to foster new hi-tech industries in combination with high levels of investment and research by companies themselves.

“It’s been going on since the 1980s: successive governments, bipartisan, have built up a system where the government invested in what we called start-ups — before other countries called them that! — which entailed mainly loans.

“A lot of the companies failed, but if we got three or four successes for every 20 companies it paid for itself.”

Across the five years to 2005, civilian research and development was 4.5 per cent of GDP on average, or 30 per cent to 50 per cent higher again than Japan or Germany. By 2008, per person venture capital investment in Israel was 2.5 times greater than in the US, 80 times greater than in China and 350 times greater than in India, according to Dan Senor and Saul Singer in their book Start-Up Nation: The Story of Israel’s Economic Miracle.

A decade later, Israel isn’t talking so-called STEM jobs — it’s walking the walk, with more PhD-trained engineers per capita than any other country. It’s home to more than 320 research and development centres run by Apple, Google, IBM, Samsung, Intel, Amazon and Microsoft.

Its hi-tech economy spans health, agriculture, water, automotive, environmental, aerospace and fintech. About 45 per cent of its exports are hi-tech, including $US3 billion ($3.86bn) in cybersecurity technology, which is about 7 per cent of the global total. Another $3bn of exports is agricultural technology.

Almost 100 Israeli companies are listed on the US Nasdaq index in New York, too, more than from continental Europe.

Australia has sought to harness some of this talent. In 2015 the Turnbull government established a “landing pad” in Tel Aviv, Israel’s biggest city, to bring together emerging local and Israeli firms and entrepreneurs.

Unlike most countries its defence technology is all homegrown. “Everything that goes into our planes and ships and boats, the technology is all Israeli,” Sofer says.

Its economic and political relationship with Australia has “probably never been as strong as it is today”, the ambassador says. Combined imports and exports between Australia and Israel of less than $1.5bn last year belie far stronger academic, financial and cultural links.

“We have 16 companies traded on the ASX and about 15 are waiting to be quoted — that shows the level of confidence in Australia.”

Fossil fuels meet the bulk of Israel’s demand, but solar figures prominently. “We invented it (solar). It started in Israel. In fact every house in Israel by law has to have a solar panel on the roof,” Sofer says.

Sofer is careful to avoid discussing domestic politics when asked about the Labor Party’s emerging divisions over whether to recognise Palestine without qualification.

“I don’t have a point of view on Australian politics. I’m careful not to. But I think that it’s important to remember there are an enormous amount of issues going on internationally, some shocking, some frightening. Look at civil wars in Africa, Sierra Leone. To take, out of all the quagmire in the world, and single out one country is problematic,” he says.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout