Hitchhiker's guide to the 1960s and 70s

ONCE upon a time you could stand by the side of the road with little except your faith in humanity.

SERIAL killer Ivan Milat has a lot to answer for. The art of hitchhiking, it seems, has been all but lost. It was not always so.

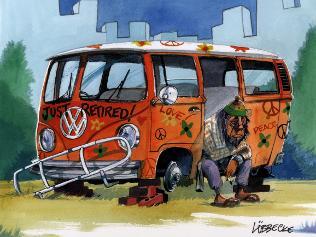

Once we were road warriors, spreading across the country faster than a plague of rabbits as we stood patiently clutching hastily written signs. And somebody, eventually, would always stop: the farmer in the Ford Fairlane, the bored truck driver or the hippies in the clapped-out kombi. Some of us would gain enough confidence to take our skills overseas.

Hitchhiking in a foreign country was not for the faint-hearted, but it was made easier in Europe 30 years ago through the work of Ken Welsh. Welsh's book, Hitchhiker's Guide To Europe, was a bible for travellers for 25 years and also inspired Douglas Adams to write his comedy series The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

It was a matter of pride that The Guide could get you around Europe for less money than any travel book of the time. American college kids under the delusion they were slumming it with the slicker Frommers Europe on $10 a Day were quickly disabused of the idea when they learned the guide promised it could get a frugal traveller around Europe for as little as $25 a week.

This was because, along with the usual tips on cheap restaurants and lodgings, the guide contained invaluable information on where to hitch and, equally importantly, which places to avoid. Hitchhiker's Guide To Europe also published tips from fellow hitchers.

What it could not predict, of course, is who would pick you up. It should be noted that hitchhikers in the 1970s were not as clean-cut and fresh-faced as the youth of today. Looking like an overweight version of Charles Manson was not conducive to catching a ride.

This may have been the reason I usually came in last during the races a group of us would sometimes have. It may also have something to do with the dearth of the nymphomaniac drivers I was always assured were around but I never met, despite an undying optimism.

My first lift in Europe - from Calais to Paris in a truck with a bunch of Welsh guys getting stuck into Johnnie Walker Red, baguettes and Damson jam - set the tone for the next year.

There were two great things about hitching. One was the total sense of freedom. There is nothing better than standing by the side of the road on a crisp morning with an intended destination but not really caring if you end up somewhere else. Of course, unexpectedly ending up in the wrong country was a little disconcerting.

On one memorable ride, I hopped into a car with a businessman, whipped out my French phrasebook, and asked him if he could take me to Zurich. He replied in eloquent but incomprehensible German and eventually deposited me in his homeland.

The second thing was the people. Hitchhiking was generally a window to humanity's better nature and should be exhibit A if the aliens ever land and demand to know why humans should be allowed to run the planet.

People did extraordinary things to help humble travellers. Once classic case involved a female friend and our attempts to get out of Paris. We'd caught the train to the town of Meaux with the intention of finding a campsite. Unfortunately, the site was closed and, with evening closing in, we tried to hitch on towards our ultimate destination of Luxembourg.

We were picked up by Francoise, who didn't speak English but gleaned enough to realise that we were on the wrong road.

Eventually, the communication barriers got too much for Francoise and we set off on a 20km jaunt through the French countryside to find a friend of his.

Mireille invited us in for drinks, fed us and allowed us to set up the tent in her back garden. When we trooped in for breakfast the next day, she insisted on taking us to the nearest motorway toll gate.

There were many instances of people going out of their way to help, and often they would buy a starving young hitcher a cup of coffee or even a meal. The only steak I ever ate in Britain was courtesy of someone who gave me a lift.

And then there was the bloke in the Citroen van at the French town of Vendome who appeared to be on mission when it came to picking up hitchhikers. The back of his van was like a mini United Nations, at one stage holding two French girls, two Australians, a Dutchman and an Italian couple.

Another time, I was standing outside of Kassel, in Germany, heading to Hamburg, when a yellow Volkswagen pulled up. Rudigen was headed to see his sister in Berlin and told me that, provided I didn't mind travelling through a few towns on the way, I was welcome to come. Three fascinating days later we arrived in Berlin, where his sister and her boyfriend put me up for the night, took me to a jazz concert and shouted Guinness until 4am.

However, it's true that some rides are a little more exciting than others. French drivers were particularly frightening.

Undoubtedly the worst of these was when a fellow West Australian and I were travelling from Perpignan, in the south of France. We were picked up by a guy in a Citroen Dyane, a small utilitarian car whose long list of optional fixtures apparently included seats. This version had just two canvas seats in the front, so my mate clambered into the back with the packs and began the usual banter.

We quickly came to realise that our good Samaritan's driving skills lay somewhere between those displayed by Steve McQueen in Bullitt and a kamikaze pilot. One of his more disconcerting habits, as he sped insanely down winding mountain roads, was to turn round to talk to my friend. Being French, he felt obliged to gesticulate - with both hands. His piece de resistance was speeding across a four-lane highway without slowing or bothering to check for traffic. The good news is that we made 207km in two harrowing hours. The bad news is that, even now, the sight of a Dyane causes cold sweats.

Hitching may have brought unparalleled freedom but sometimes that came down to freedom from getting a lift. The time it took to get a lift was often inversely proportional to the affluence of those driving by. It was not unusual to wait four or five hours for a lift, and sometimes it was necessary to pitch the tent by the side of the road.

All hitchers were ready for delays, and it was standard practice to travel with essentials such as bread, cheese and wine. A long drought was usually broken by the welcome sight of a battered car clattering down the road.

Hitching had its frustrations, its dangers and its unpleasant moments, but it was by far the best way for a young traveller to see the countryside and meet the people. It also reinforced a belief that most people in the world are more inclined to help each other than plot to do harm.