Global economic storm clouds gathering

Financial markets have been behaving as if the world economy were Wile E. Coyote, defying the inevitable plunge into the canyon below.

Financial markets have been behaving as if the world economy were Wile E. Coyote with legs spinning fast in thin air, momentarily defying the inevitable gravitational plunge into the canyon below. Share prices dived 12.5 per cent in the last three months of 2018 in Australia and by a similar amount in the last four weeks of the year in the US. The S&P/ASX 200 is showing no capital gain since late 2006.

The economy will be at the centre of the political struggle as Scott Morrison and Bill Shorten return from holidays in the run-up to the election campaign. Mr Morrison has warned of international “storm clouds” ahead, promising to preside over a strong economy without increasing taxes. As for Mr Shorten, he is pitching a range of new taxes as well as superannuation changes with a calculated appeal to low and middle income earners while delivering larger budget surpluses as insurance against a global downturn. Ahead there is uncertainty and risk.

Investors have been selling shares and looking for safety in government bonds, with strong demand pushing the interest yield on Australian 10-year government bonds below 2.2 per cent last week — the lowest in two years and a full 0.5 per cent drop since November. US government bond yields have fallen by a similar amount.

Bond markets matter. While central banks set the short-term interest rates for the whole economy, bond markets dictate the rates for longer-term lending. When there is strong demand for bonds — for example, when investors think shares are too risky and they want the security of a government guaranteed return — the interest return (or yield) on bonds falls.

While Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe has been advising for months that the next move in official short-term interest rates is likely to be an increase (although not for some time), the money market has started betting that a deteriorating economic outlook will force it to cut. These are dramatically different perceptions of the outlook.

Last Friday, the money markets were trading on the basis of a one in three chance of a 25 basis point rate cut by next October.

Yet the latest report from the US shows its economy is still running flat out.

The monthly labour report showed non-farm payrolls rose by 312,000 in November, the strongest rise in 10 months, while October hiring also was revised higher. Unemployment rose slightly to 3.9 per cent but only because the strength of labour demand is persuading people who had given up getting a job to have a go.

In Australia too, the labour force has continued its remarkable strength. The number of people with work has been rising at an annual rate of 2.5 per cent for the past two years, much faster than the underlying rise in the working-age population and by far the best stretch of employment growth since the final years of the Howard government, before the financial crisis struck. There are some signs of softening in several of the major economies, most notably China, but the slowing is modest.

So why are markets so fretful? Are we really staring at the prospect of a downturn or even a recession in the year ahead? The immediate trigger for the market’s funk was an innocently upbeat four-paragraph summary of the outlook for the US economy from the Federal Reserve following its meeting in November that foreshadowed further gradual increases in its benchmark interest rate across 2019. The market reaction showed investors believed further rate rises would be a grave mistake, choking the US economy.

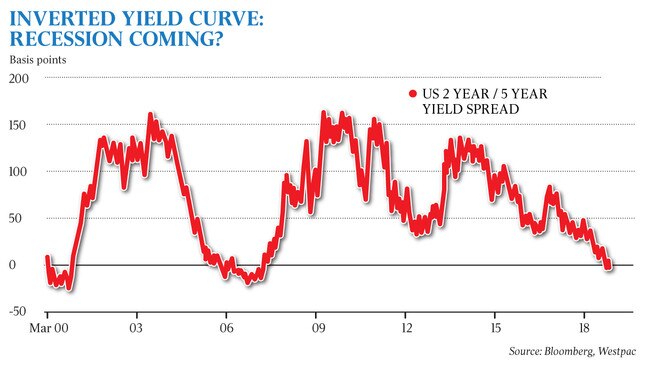

The reaction of bond markets meant that long-term interest rates dropped below short-term rates, a rare state of affairs known as an inverted yield curve. You normally expect to pay more to borrow longer term. However, towards the end of last year, markets were trading on the basis that the Fed would keep pushing up short-term rates but then would be forced to slash rates as the economy tipped into recession.

Every US recession since 1969 has been preceded by an inverted yield curve, although markets are not infallible. The phenomenon of long-term interest rates dropping below short-term rates has occurred several times without a recession ensuing.

ANZ’s head of Australian economics David Plank says the sharemarket provides little clue to the outlook for the economy, recalling that equities remained strong in 2007 and into 2008, providing no hint of the financial crisis around the corner. “But myself and others pay a lot of attention to the yield curve and credit spreads,” he says.

In 2007 and into 2008, long-term rates dropped below short-term rates, while lenders started demanding much higher premiums to extend funds to riskier borrowers. As fears the US Fed would lift rates too far took hold late last year, those premiums again blew out from three percentage points above the government bond rate for 10-year debt to five percentage points, while new issues of so-called junk bonds dried up altogether for the first time since the financial crisis.

There is a long record of central banks tipping economies into recession by raising their rates too far and too fast. Australia’s last recession was precipitated by the Reserve Bank lifting its cash rate to what now seems an unbelievable 17.5 per cent. The return to “normal” after years of near-zero interest rates by the world’s major central banks was always expected to bring some financial disruption.

But whether the Fed’s planned gradual increase in rates — it has been looking at lifting its benchmark rate to a maximum of a little more than 3 per cent by 2020 — would have been enough to bring the US economy to a shuddering halt is debatable. The picture is clouded by the fact the Fed is also running down its holdings of government bonds, which it bought in the wake of the financial crisis in an effort to lower market interest rates. So far the combination of lifting rates while reducing the size of the Fed’s balance sheet does not appear to have materially slowed the economy.

“It looks like an over-reaction,” says Commonwealth Bank chief economist Michael Blythe, who says the US economy still has strong momentum. The pessimism that has marked perspectives on 2019 partly reflects a belief that 2018 was as good as it gets and it is all downhill from here. The severity of the market reaction shows the herd of investors all shifting their stance at once.

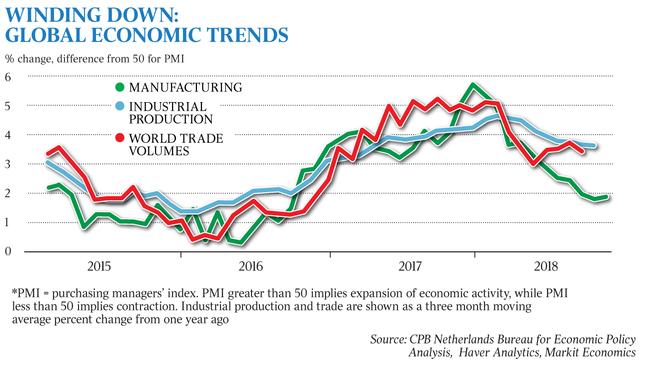

This time last year, the world was looking forward to a simultaneous upturn in the economies of the US, Europe, Japan and much of the emerging world. In the US, that upturn was power-assisted by massive tax cuts and a lift in government spending.

Europe’s economies now appear to be slowing, having never lived up to the hopes held for them early last year, while Japan’s economy contracted in the September quarter. The stimulus effect of Donald Trump’s tax cuts on the US economy is expected to have run its course by the latter half of this year, which increases concerns about further potential tightening of monetary policy.

China is the biggest worry. Its growth rate has been slowing for the past eight years as authorities try to engineer a shift in the nature of its economy, making it less dependent on exports and business investment, and more reliant on household spending. At the same time, they are trying to reduce debt levels that have been inflated by repeated efforts to stimulate the economy. The past month has brought disappointing retail sales and industrial production reports, while business surveys show trading conditions are becoming more difficult. The government is responding by making it easier for banks to lend, and promising more infrastructure spending.

While these shifts in the Chinese economy have affected most of its trading partners — exports to China from the US, Germany and Japan are all down — Australia’s trade with China has never been better, with export growth of almost 30 per cent last year. Australia has benefited from the efforts of China’s authorities to reduce urban air pollution, which have forced the closure of inefficient steel mills that depended on domestic supplies of coal and iron ore, in favour of large modern plants that work best with higher-quality Australian materials.

The Commonwealth Bank’s Blythe says Australia is perversely well positioned to gain from further slowing in the Chinese economy, as government efforts to stimulate activity through infrastructure investments will boost its purchases of iron ore and coal. However, our economy would be vulnerable to any serious downturn in China, with reduced prices and volumes for exports ultimately flowing through to reduced income for everyone.

While economists are factoring in the likelihood of slower global growth this year, it would take financial disruption — a debt crisis of some sort — to spark a more serious downturn of the sort that markets appear to be envisaging.

The Bank for International Settlements (a central bank for the world’s central banks) is worried about the US corporate debt market, where borrowing now exceeds levels during the financial crisis and is being driven by companies with the weakest balance sheets. It says 80 per cent of these loans have weak covenants, giving lenders little recourse if things go wrong. The collapse of the US junk bond market contributed to the global recession of the early 1990s.

The BIS is also worried about the impact of political uncertainty in Italy and Britain on European banks, which have struggled to rebuild capital in the wake of the financial crisis.

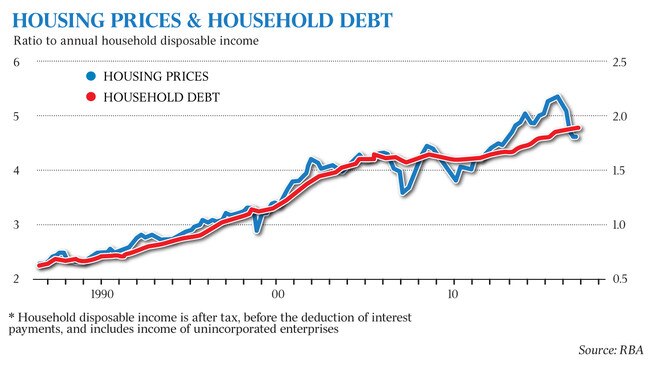

In Australia, the elevated level of household debt is the most obvious risk, although the Reserve Bank believes it is unlikely to be the cause of a banking crisis under any plausible scenario. The Reserve Bank does think the high level of debt could cause households to cut their spending more sharply in any downturn and this could make any slowing of the economy worse.

Financial crises have proven impossible to predict. Risks can be highlighted but never the timing of trouble. Indeed, economists have a poor record in picking turning points in the economy.

ANZ’s Plank says that by the time economists receive official data on the economy, it is already a month or more old. “We don’t know where we are until a few months after we’ve been there, and then the historic data is subject to revisions,” he says.

There are few leading indicators beyond the very short term and most, such as surveys of business intentions, are reliable for only a few months out.

Plank says the market pricing of Reserve Bank rate moves has no predictive value. “Right through the tightening phase from 2004 to 2007, the market was under-predicting where rates would go, while there have been plenty of times when the market prices rate cuts in the middle of a hiking cycle.”

But while markets generate noise, they also can contain information. Plank says that while the yield curve is not infallible, it has proven historically to be more reliable than other indicators. It says there is a risk of a slowdown and that the Federal Reserve will make a mistake by lifting rates too far.

Under a tweet attack from Trump and facing the turmoil of markets, US Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell has backtracked from the breezy confidence he was expressing last November. Earlier this month he commented that the Fed’s sales of government bonds were not on “autopilot” and could be slowed if the economy looked to be in trouble. “You do have this difference between, on the one hand, strong data, and some tension between financial markets that are signalling concern and downside risks,’’ he said.

He likened the position to 2016, when the Fed kept rates steady for most of the year because of concerns about slowing growth in China, saying he was “listening sensitively to the message that markets are sending.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout