George Brandis in the box seat for Britain’s Brexit turning point

George Brandis’s arrival in London as high commissioner comes amid the trauma of Britain’s divorce from Europe.

“We haven’t seen anything like this since the 1530s.”

For George Brandis, Australia’s new high commissioner in London, a senior backbencher’s quip about Brexit, overheard at The Spectator’s summer garden party, confirms the magnitude of what Britain is facing.

Henry VIII’s divorce and elevation to the head of the Church of England in 1534 mauled his kingdom’s relations with the continent. Brexit, barely more than six months away, will do the same, in the process tearing apart the nation’s political fabric.

“There is a real consciousness that this is a turning point in British history,” Brandis tells The Australian at Stoke Lodge, the £50 million-plus ($87m) mansion just a stroll from Kensington Palace and home to Australian high commissioners since the 1950s.

Attorney-general for more than four years in the Abbott and Turnbull governments, Brandis succeeded Alexander Downer as the nation’s top man in London in March.

He welcomes the appointment of Marise Payne as Foreign Minister following Malcolm Turnbull’s departure. “Marise has been a very close friend for more than 30 years and I very much look forward to working with her,” Brandis says, adding that Julie Bishop was “a very good friend and colleague”.

His final chief of staff, Liam Brennan, who worked nine years for Brandis, says of the Liberal leadership turmoil: “As one of the leading moderates during the Abbott and Turnbull years, I am sure George would be discreetly delighted with the outcome last week.”

But all that is worlds away as Brandis takes up a box seat for Britain’s tortuous negotiations to leave the EU. In his first interview since arriving in April, Brandis says: “Since the second world war the two fundamentals of British foreign policy, and more broadly Britain’s sense of place in the world, have been its relationship with Europe and its relationship with the US. And those two fundamentals are less settled than they have hitherto been.”

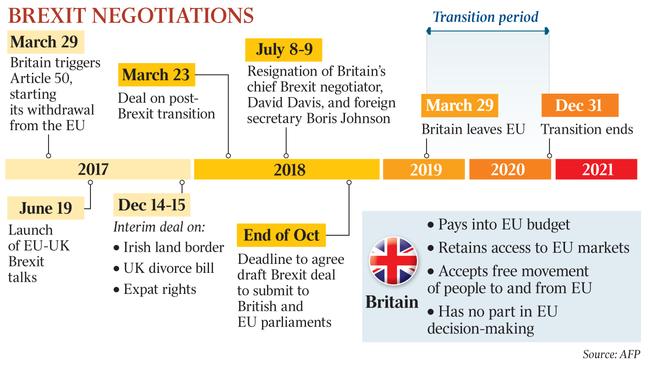

That’s putting it mildly. On March 29 next year, when the two-year notification period ends, Britain will cease to be a member of the EU, the political and economic colossus London fought so hard to join in 1973.

Relations with the US are at a lower ebb, too, following what was billed a disastrous visit to Britain by President Donald Trump, who appeared to praise Prime Minister Theresa May’s rival, Boris Johnson, and savage her Brexit strategy.

“There are many here who are not quite sure how to deal with Trump,” Brandis says.

Indeed, British Investment Minister Graham Stuart, visiting Sydney recently, took a veiled swipe at the US President, who this year claimed trade wars were “easy to win”.

“We don’t believe trade wars are easy to win and don’t believe they lead to victories for anybody; they are lose-lose,” Stuart tells The Australian. “We’re as clear as our Australian allies that rules-based liberal world order and the WTO are things which we strongly support. We think the rising tide of protectionism in some quarters is a mistake and will make the world a poorer place.”

Australian influence in London is as high as ever. The bumptious Trump’s esteem for Turnbull was well known in diplomatic circles.

“There is quite a lot of anxiety among certainly the political and official classes here, and there is a very conscious reaching out to old friends, and Australia is pretty much at the front of that queue. This is a very good time to be an Australian in the UK,” Brandis says. “If people use metaphors these days, it’s more of older and younger siblings. You don’t feel patronised any more.”

Brandis, 61, would know. He was a Commonwealth scholar at Oxford University in the early 1980s, when Margaret Thatcher was throwing her weight around, demanding what would become an annual “rebate” from the EU.

Today, Britain faces a £30 billion-plus “divorce bill” and the prospect of a damaging collapse in trade. More than 40 per cent of Britain’s trade is with the 27 other EU nations, while no more than 10 per cent of any of theirs is with Britain, putting the latter at a distinct disadvantage at the negotiating table.

Brandis, whose arrival was delayed until late April by a tennis injury, has already met most of the senior cabinet ministers, including May — who he already knew from her time as home secretary, when their ministerial briefs overlapped — and incumbent Home Secretary Sajid Javid, the bookies’ favourite to replace her. He has met the heads of HM Treasury, the Bank of England and, of course, the Queen, to whom he attributes an ageless perspicacity.

“There’s an awareness, a slightly guilty one, that for many years the relationship was neglected, benignly,” Brandis says.

Britain has been thoroughly ill-prepared for the negotiations. The British cabinet and the parliament are divided over how severe the separation with the EU should be. Brandis has arrived at a time of extraordinary political tumult.

After signalling a “hard” Brexit in a series of speeches last year, May released a so-called Chequers agreement last month that envisaged Britain accepting EU rules, remaining in the Customs union and deferring to the European Court of Justice when it exited. It was far too “soft” for hard Brexiteers Johnson and David Davis, who resigned from the cabinet.

Yet May, who became Prime Minister following Britain’s Brexit vote in June 2016, has defied her critics, tenaciously hanging on. Indeed, her political enemies are reluctant to challenge her — under Conservative party rules, the victor is secure for 12 months as leader.

“The degree of complication and sophistication of the different scenarios under which conceivably Britain could leave has developed its own cabalistic language. One person at a recent dinner was discussing whether the best option was Canada-plus, bespoke Norway or reverse Ukraine,” Brandis says, referring to the different arrangements non-member countries have with the giant bloc.

May, at least, has the advantage of an opposition, however resurgent, distracted by continual accusations of anti-Semitism, with a leader, Jeremy Corbyn, who lacks the support of his parliamentary colleagues.

Despite its electoral gains in the general election last year, Labour has been paralysed by a surging and increasingly left-wing membership base — at loggerheads with the bulk of its MPs.

“The fundamentals of liberal democratic governance, which people of my generation thought had been settled by the end of the Cold War, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the discrediting of communist idea, are now being challenged once again in ways I never expected to see, sometimes from within parties ostensibly in the political mainstream,” Brandis says.

Labour’s membership rose from 0.4 per cent of the electorate in 2013 to 1.2 per cent, or 550,000 people, this year, more than quadruple the Conservatives’ total.

“The survival — let alone the triumph — of the liberal democratic values of the Enlightenment cannot be taken for granted as, since the 1990s, we have tended to do,” Brandis adds.

John Denton, the new Australian secretary-general of the International Chamber of Commerce based in Europe, says the uncertainty around Brexit is “weighing heavily” on investment in Britain.

“A situation compounded by growing trade tensions globally,” he says. “It’s vital for business to have certainty regarding the long-term future of the EU-UK economic relationship.”

That seems unlikely. Even if the government reaches a deal with the European Commission, the 650-member House of Commons needs to ratify it — no mean feat for a government without a majority and facing a resurgent Labour Party embroiled in an anti-Semitism scandal. Then, each of the EU members needs to endorse it.

At the same time, no deal at all is hard to imagine, mainly because Britain isn’t prepared for it. About 6000 trucks a day roll on to boats in Calais and roll off in Dover. All these would need to be checked under default World Trade Organisation rules. If it took two minutes each, trucks would bank up more than 30km within hours. The inspection machinery doesn’t even exist, on either side of the Channel. Dotting the Northern Irish border with boom gates would breach Good Friday rules.

Brandis suggests the strategy for Britain should be to clinch the best deal it can, no matter how bad it actually is. The government, meanwhile, needs to show voters there’s a dividend from Brexit, such as through a free trade agreement with Australia. “The easiest deal the UK will ever do is with us,” he says.

While formal negotiations for the mooted Australia-Britain trade agreement — a tangible “deliverable” of Brandis’s tenure — can’t start until Britain has left the EU, informal working groups have met four times already.

Waiting in the foreigner queue at Heathrow and Gatwick while Germans and Italians stream through the fast lane could be a thing of the past after Britain leaves the EU.

“Free trade agreements are about more than articles of commerce; they involve potentially large hinterland of other issues, in which movement of peoples is almost always one of them,” Brandis says.

Stuart agrees. “Any trade agreement tends to look at issues around visas and I would expect this to be no different,” he says. “We look to do a deal with Australia as one of the first and most important deals we can do globally.”

Its trade policies in tatters following Brexit, Britain is scrambling to start negotiations with New Zealand, the US and Canada too, and even join the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

“Australia deserves great credit for having played a role in resurrecting the agreement, The 11 countries in the TPP constitute a similar share of global GDP to the EU27,” Stuart says, referring to the EU minus Britain.

Brandis, asked to reflect on his greatest achievements as attorney-general, singles out the several tranches of national security legislation — “the most fundamental rewriting in a generation”.

“We got the balance right,” he says. “It wasn’t just a grab for state power.”

Is China a source of anxiety in Westminster too? “When foreign interference is discussed here, almost invariably the conversation is about Russia. (But) people are interested in our foreign interference laws.”

Last year’s marriage equality legislation “will live as a legacy of the Turnbull government forever”, he says. “And I was of the view that the AG must always stand up for the rule of law, including independence of the judiciary. I always did.”

He won’t be drawn on the relative quality of Australian and British domestic politics because Brexit up-ended British norms.

“But players here, and particularly the parliamentary players, are aware of their historic roles in a way that is unpretentious but is nevertheless self-conscious, Brandis says

Perhaps that’s one difference.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout