Frydenberg should surprise us with early budget surplus

It would help the Coalition during its years in opposition.

It must be tempting for the Coalition to defy precedent and tighten its fiscal belt ahead of next year’s election in a bid to stun everyone and hand down a budget surplus this financial year, rather than merely forecast one for 2019-20.

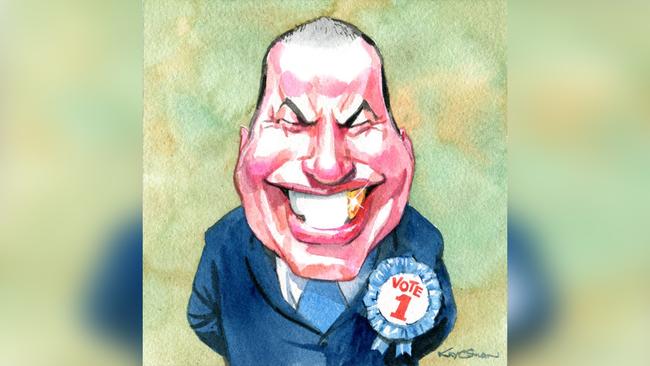

Yes, it would be a herculean task at this point in the economic and political cycle, make no mistake. Last year’s budget forecast a deficit of $14.5 billion for this financial year. But courtesy of improved revenue numbers the new Treasurer, Josh Frydenberg, is expected to use the mid-year economic and fiscal outlook on Monday to announce the deficit has dropped to single digits.

Why not go further and do what’s necessary to squeeze it into a small surplus? There are few legislative opportunities to do so, with the parliamentary year over and minimal sitting periods scheduled for early next year. In that sense, any drive for a surplus this financial year probably needed to begin months ago. After all, there are only six months to go in this financial year.

But funding cuts can be imposed without legislation. And large infrastructure and defence spending, for example, can be shuffled from one year to the next to improve the budget bottom line. The government can even do tricky things such as hitting up the Reserve Bank for money to help attain the budget surplus.

To be sure, Labor and the media will respond rather cynically to such actions. But the outcome may be worth the criticism, certainly in the long run.

This government has little or no chance of winning the next election. Delivering a surplus, even with clever accounting, would give the Coalition in opposition something significant on which to hang its six years in power: a way of condemning the new Labor government as fiscal wreckers if it allowed the budget to drift back into deficit.

Given the slowdown in global growth, threats to the housing sector and a weakening Asian market for our commodities, there is a fair chance the forward estimates are too optimistic. Such nuance won’t matter if the Liberals get the budget back to surplus at the end of their tenure and it goes back in the red as soon as Labor wins office.

The politics of massaging a surplus may even help the Coalition minimise the size of a defeat next year, making it easier to be competitive in opposition.

The improved budget bottom line that makes it possible even to countenance a surplus this year is a mixture of good luck and good government. The luck comes in the shape of better than expected nominal GDP numbers, which include a mixture of higher company, capital gains and pay as you go tax receipts. But the Coalition also has dramatically curbed growth in government spending, largely sticking to its fiscal rules.

So in essence revenue growth has been stronger than expected, and spending has been relatively well contained, compressing the deficit. At the halfway mark of this fiscal year, projecting a single-digit deficit makes forecasting a surplus for 2019-20 a little more credible. But, politically speaking, the government simply won’t get the credit for it. Liberal strategists who think otherwise are kidding themselves. They need an actual surplus for credit to apply.

Voters are cynical about forecasts and rightly so. Wayne Swan notoriously handed down multiple forward estimate surpluses when Kevin Rudd was prime minister yet went on to deliver three of the worst budget deficits in our history. I remember sitting in the gallery listening to Swan’s budget speech crowing about delivering surpluses that never materialised, followed by a steady diet of humble pie in the years after that.

Yes, the effects of the global financial crisis lingered longer than expected, but Labor also never got its spending under control. And the forecasts were based on growth estimates that were entirely unrealistic.

Even if the forecast surplus for 2019-20 does materialise, by that time Labor almost certainly will be in power. It therefore will get the credit for handing down Australia’s first actual surplus in more than a decade. Or, through a combination of changing economic circumstances and Labor’s different policy and spending patterns, the surplus won’t happen.

Yes, the Coalition will seek to score political points if that happens, but doing so would be far more effective if it tightened the fiscal belt a little bit more now and turned the single-digit deficit into a single-digit surplus. It would sharpen the contrast with Labor. If Labor inherits a deficit and the Coalition blocks measures in the Senate that would deliver revenue, Labor will blame the absence of a surplus on Coalition obstructionism.

For example, Labor’s dividend imputation changes are unlikely to pass the Senate if the Coalition and the crossbench oppose the policy. Whatever you think of Labor’s plans, they have been costed to add $5bn to the budget.

It’s too late to surprise us with a MYEFO surplus announcement but the Treasurer could institute such a shift in time for the budget next year. Doing so just ahead of the election would be a strong platform for Frydenberg, who has emerged from the pack of potential next-generation leaders as the man most likely.

In opposition (yes, I keep assuming the Coalition will lose the election) Frydenberg’s standing would be substantially elevated if he’s the ex-treasurer who brought the budget back into the black after so many years.

But he will need to convince Scott Morrison this course of action is worthwhile. Prime ministers are always more profligate with their spending than treasurers. I recall Peter Costello complaining about this in interviews I did with him for John Howard’s biography.

On most occasions prime ministers get their way, but Morrison may not have as much authority in this regard as a prime minister usually would. He still has his training wheels on. And Frydenberg could secure the support of long-time Finance Minister and Senate leader Mathias Cormann.

Cormann is the only continuous member of the powerful expenditure review committee throughout the Abbott, Turnbull and Morrison governments. His authority behind a push to craft a surplus this financial year would be necessary for Frydenberg to make it happen.

The polls keep telling us the Coalition leads Labor as preferred economic manager. To preserve that status, handing down an early surplus would be valuable. But some deft political thinking is required to make it happen.

Peter van Onselen is a professor of politics at the University of Western Australia and Griffith University.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout