Flu pandemic sailed in as the Great War drew to a close

First it wreaked havoc across Europe, then it reached our shores.

One hundred years ago on the morning of January 25, 1919, Sydney residents woke to read in the newspaper of a suspected case of influenza in the city.

Over the next week, seven returned servicemen would go down with the flu as well as three hospital staff who had looked after them. Within a few days, more cases began to appear throughout the city and from late February the number of cases increased day by day. It was the beginning of what was to become the greatest social and public health disaster in Australian history. But where did this virulent virus come from? How did it emerge, who was infected, and how did we react?

The Spanish flu, as it came to be called, killed more than 50 million people around the world in 1918-19. Australia waited a little longer than most other countries, but from late January 1919, the country’s days were numbered.

The 1919 flu pandemic was the worst public health disaster Australia has experienced. The whole country was affected, more than 15,000 people died and possibly as many as 1.8 million people caught the disease over a period of four months. In NSW alone more than 500,000 people caught flu in 1919 and more than 6200 died.

Australia was no stranger to flu epidemics. At least four influenza epidemics occurred between 1836 and 1891. The one in 1890-91 was by far the most significant in the 19th century and there were more than 200,000 cases in NSW alone. But nothing could prepare Australia for the pandemic of 1918-19.

It is difficult to pin down the origins of the 1918-19 pandemic. Most evidence points to Fort Riley in Kansas in the US where, in early March 1918, a wave of pneumonia affected many soldiers waiting to travel to Europe. From there the infection was most probably carried by American troops to France, where it quickly spread to the local population. From there it spread throughout western Europe and by October more than one million had died from the flu. Aided by a modern system of international transport, the disease spread across the world.

Many Australian and New Zealand troops returning home carried the infection with them. From late October 1918, Australia began to experience a stream of ships returning from Europe and South Africa — many transporting troops infected with influenza. By the end of January 1919, more than 326 troops suspected of having flu, or the misfortune to have had contact with someone who did, were placed in quarantine at the North Head Quarantine Station.

In New Zealand a particularly virulent form of influenza had swept through the country during November and December 1918, and within six weeks more than 8500 people had died. It was without any doubt the greatest natural disaster New Zealand has ever experienced.

But what caused this pandemic and what did we know about it? The 1918-19 influenza pandemic was caused by a virus not discovered until the 1930s. The influenza virus is a zoonotic infection nurtured in wild birds, and has been so for tens of centuries. Many variants exist, some transferable to other animals such as ducks, chickens or pigs. Type A flu viruses are the ones that cause disease in humans. About one-third of people infected never become ill and show no symptoms but can still transmit the infection to others. Influenza can also unleash secondary bacterial infections such as pneumonia and bronchitis.

Although flu cases began to appear in large numbers in Australia in late February to early April, the pandemic was most severe in the period from the beginning of June until early July. During this time almost 6000 people were admitted to hospital suffering from influenza. But this was the mere tip of the iceberg, as tens of thousands were ill with influenza throughout the country, the majority confined to their homes.

From the evidence we have it is clear that the flu pandemic came in two distinctive waves, the first in mid-April and the second in late June. While there is no actual evidence of the number of people who caught it in 1919, in Sydney alone possibly 37 to 40 per cent of the total population caught the flu.

Despite our long history of flu epidemics, the pandemic which affected Australia in 1919 had features never before experienced.

Up until this, early influenza outbreaks had largely targeted the very young and the very old. By contrast the 1919 flu was most severe on people aged 25 to 39. In Sydney this age group then made up 27 per cent of the population yet contributed 45 per cent of all flu deaths. Fifty-eight per cent of all hospital admissions and flu deaths in NSW were also aged between 25 and 39. Of particular note is the fact that for these ages, the male death rate was almost double that of females.

While the pandemic was no respecter of wealth and position, striking down medical practitioners, lawyers and schoolteachers as well as government workers, lower-class groups suffered the highest mortality. Those whose jobs brought them into regular contact with fellow workers and the public were most at risk.

Influenza affected every aspect of Australian life. In NSW 5000 marriages were destroyed by the death of one or both partners and many children found themselves without parents.

It is important to note that in 1919 while the flu virus was highly infective the real killer was pneumonia. In a number of cases the virus managed to lodge deep inside people’s lungs, causing a deadly form of viral pneumonia.

There is little doubt that the medical profession were ill prepared and ill equipped to deal with the outbreak. Very little was known about viral infections and most believed they were simply confronting a bacterial disease. Antibiotics, which could have prevented many deaths, had yet to be discovered, and it would be another 34 years before the nature of influenza was better understood.

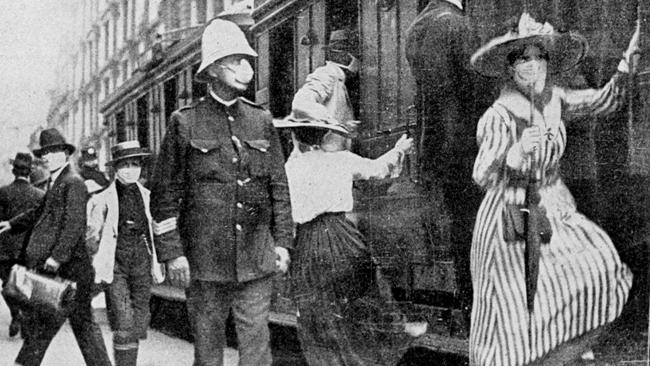

Given this, the medical profession was forced to rely on more prosaic measures such as quarantine, isolation, the use of sprays, disinfectants and masks, as well as telling people to avoid public gatherings and that at the first sign of symptoms they should go to bed for at least four days. Public confidence in the medical profession during the pandemic remained at a very low level.

In late 1918, a vaccine was prepared in Sydney from culturing the sputum of flu patients at the quarantine station supplemented by a mixture of streptococcal and staphylococcal material. Initially two free doses were offered to the public, but such was the public response that supplies soon ran out.

Inoculation depots were established throughout Sydney but within days they were overwhelmed as tens of thousands fought to get into the queues. In NSW almost 500,000 people sought vaccination. But did vaccination provide any defence against the flu? Unfortunately there is very little evidence, apart from figures for 12,000 patients treated in public hospitals. Of those inoculated about 11 per cent caught flu compared with 16 per cent of those not inoculated. A survey of 752 medical staff in Sydney hospitals who had been inoculated revealed that one month later 684 — or 91 per cent — had caught flu.

And how did the government react to the pandemic? Late in 1918, the commonwealth moved to quarantine all ships arriving where any history of flu cases existed. In November 1918, the commonwealth called an influenza conference and all states agreed to a 13-point plan, with the commonwealth assuming responsibility for quarantine, interstate transport, border protection and the closure of public places, while all the states agreed to immediately notify the commonwealth the moment flu broke out within their borders, whereupon the commonwealth would restrict movement across state borders.

Over the next few weeks relations between the states and the commonwealth plummeted as disputes broke out. NSW accused Victoria of not notifying the commonwealth and other states of its first case of influenza. Tasmania was accused of interfering with interstate trade by placing restrictions on shipping. Western Australia held up the intercontinental train while NSW prohibited entry into the state of anyone from South Australia. A day or so later, the Queensland government closed its border with NSW.

By February it was clear the commonwealth agreement was in tatters and increasing influenza cases saw all states electing to go their own way. NSW instituted a wide range of restrictions and the closure of all libraries, theatres, schools, churches and public halls, apart from placing restrictions on people wishing to enter NSW.

Throughout the pandemic, panic, fear and hysteria played a central part. People avoided trams and ferries, and declined to go to church, the pub or to sporting events. Many also tried to flee from Sydney, crowding on to long-distance trains at Central Station until the government moved to restrict such travel. As flu swept through Sydney’s suburbs, people avoided neighbours and barricaded themselves in their homes.

Undertakers refused to touch dead bodies for fear of infection. Waterside workers avoided the wharves, tramway workers demanded a “pandemic pay” increase to keep them at work, while shops, restaurants, government offices and businesses struggled to stay open and thousands were out of work. Face masks were seen all over Sydney and a number of the city’s largest departmental stores introduced fumigation sprays and inhalation rooms.

The 1919 flu pandemic ranks as the greatest social and health disaster in Australian history. Nearly two million caught flu and 15,000 people died. One hundred years later, many believe we are overdue for another influenza pandemic.

The bird flu in 2005 and swine flu in 2009 were hints of what might soon come. If there is another pandemic sometime in the next few years, it will operate in a unique environment. It will strike an interconnected world characterised by unprecedented human mobility, by a globalised economy and by a 24/7 global news network.

What have we learned over the last 100 years? Critically we should marvel at the resilience and power of the microbial world. Microbes are programmed for survival and have the ability to evolve and adjust to any assault we may launch.

We are living in a time of re-emerging infectious diseases and while we are better prepared in terms of new vaccines and antiviral and antibacterial drugs, the fact remains that faced by a viral foe that mutates and evolves from one year to the next, we remain exceedingly vulnerable.

Peter Curson is a professor in the faculty of medicine and health sciences at Macquarie University. Kevin McCracken is an associate professor in the department of human geography at Macquarie University.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout