Feeling secure with facial recognition, unless at a Chinese loo

As we await the release of the much-hyped iPhone X and its facial recognition feature, entrepreneurs in China have already spotted an opportunity. Playing on the fear of some prospective buyers that snooping partners might secretly unlock their phone while they are asleep, companies are offering face masks that promise to thwart the technology.

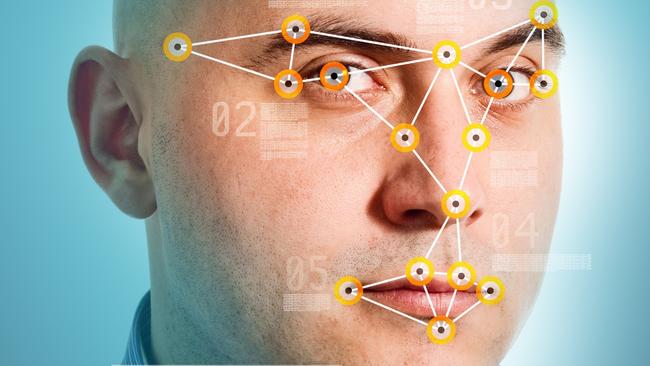

Closer to home, we had our own encounter with the new possibilities of facial recognition this week with Malcolm Turnbull securing agreement from the states to add our driver’s licence photos to a national database that could be used in conjunction with facial recognition software to identify suspected terrorists and other wanted individuals.

The federal government already has access to our passport photos but more Australians have driver’s licences, making it a richer source to use for policing.

Given the government and premiers were out there touting the agreement, it’s unlikely many Australians worried too much about the encroachment on their privacy. Everyone wants to stop terrorists. But a look at facial recognition applications in China points to the confronting new world that is just around the corner and the need for a much deeper level of public debate about the guardrails and limits we want on the many uses of this technology.

The applications for facial recognition range from the mundane to the concerning. Last month KFC in China rolled out “smile to pay”, a system that lets users select what they want to eat from a virtual menu, then validate the payment using a scan of their face. China Southern Airlines, meanwhile, replaced boarding passes with facial recognition and in Shenzhen trials have begun in taxis to certify a driver’s identity.

On the darker side, tourists in need of a bio break at Beijing’s Temple of Heaven are now confronted with a face-scanning loo-paper dispenser in the public toilet. The technology has been deployed to foil local residents who were accused of taking large amounts of toilet paper home with them. The new loo dispenser gives each patron a somewhat stingy 60cm length and imposes a nine-minute wait before it will dispense any more to the same person.

In August, police in Qingdao, home to the Tsingtao brewery, used facial recognition technology and 18 cameras to scan the faces of 2.3 million international beer festival revellers. Cameras picked out people with previous drug-use offences, and police administered drug tests on the spot, leading to 19 arrests for those found under the influence. “This is the first time we have used facial recognition technology for such a massive security check,” the local police station’s head of publicity, Li Peng, is reported as boasting.

When you start thinking about the applications, and potential pitfalls, of facial recognition technology your mind can run wild. A Stanford University study found an algorithm could correctly differentiate gay and straight men more than 80 per cent of the time, and almost three-quarters of the time for women, drawing on a sample of facial images posted on a US dating website. The algorithm proved considerably more reliable than humans, who accurately identified gender orientation only 61 per cent of the time for men and 54 per cent for women. If that technology stacks up, would it be OK for spouses to apply it to their partners if they suspect they were closeted, or parents to their children?

What other traits might an algorithm predict from our faces? And what level of accuracy would we demand before we used it to guide important decisions?

Facebook has filed a patent that would allow it to assess your mood from your face (relayed by your phone’s camera) and the changes it detects as you browse different content on its site. This could allow it to serve you up more of the content you respond to favourably (or that primes you to click on ads). It’s not quite Minority Report (a film based on psychic prediction of crime) but getting there.

On the ABC’s Q&A this week, Sandra Peter from Sydney Business Insights asked whether a driverless car should swerve to miss a child, knowing it will kill its passenger. Or should it maintain its path and end a younger life? But what if you add facial recognition into the equation? Could a wealthy citizen pay a premium to the driverless car company to ensure the algorithm would favour them in such ethical grey zone situations? Or would people whose faces were recognised to be important (such as politicians or sports stars) be given preferential treatment by the algorithm?

As with the most recent wave of technological innovations, advances in the applications for facial recognition are likely to outpace regulation and ethical considerations. And as with the public bathroom at the Temple of Heaven, companies are likely to give us little real choice to opt out of submitting to the privacy intrusion. Ethical dilemmas that undergraduate philosophy students have been grappling with for generations are now likely to be answered by programmers on a deadline.

Individually, these changes can seem minor or simply solving small practical inconveniences. The database of driver’s licence photos announced by the Prime Minister and premiers this week was not a major advance on present practice. But take the big-picture view and we are staring down the barrel of another wave of erosion of our privacy and changes to the way our society operates. These issues deserve a healthy airing in a democracy. The difficulty for Australia is that our interest levels in the democratic process are on the wane.

Polling from the Lowy Institute has revealed that just 60 per cent of Australians now say democracy is preferable to any other kind of government, with the figure falling to just over 50 per cent for those aged 18 to 29. In a separate poll last year, just 34 per cent of Australians said they trusted the federal government and 20 per cent trusted political parties. Even banks scored higher, with 41 per cent of people trusting them.

In these conditions, efforts to discuss these issues need to be redoubled so that we shape our future rather than react to what we are served up.

Fergus Hanson is head of the International Cyber Policy Centre based at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. He is author of Internet Wars: The Struggle for Power in the 21st Century.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout