Nothing observable about the undersized cement-rendered bungalow could have betrayed the acts of depravity hidden within.

One could have easily imagined an attentive mother sitting on the wooden bench outside, kids playing in the street, waiting for the evening rains to finally break the humidity.

But on one muggy, overcast morning in September last year this unremarkable house located on one of the many islands scattered throughout the Visayas archipelago would finally reveal its vile secrets.

A long investigation, initiated by the Queensland police taskforce Argos, had led an international joint operation to its doorstep.

Among a covert arrest team waiting to move in as dawn broke over the fishing village was an Australian Federal Police officer from the international liaison post in Manila.

Unable to be named because of an ongoing prosecution, the AFP officer had worked with the Philippines National Police to pinpoint the house and help secure the appropriate search warrants.

The Australian has learned a total of eight children were rescued from the house after the raid.

They had been enslaved by a pedophile ring with links to Australia, subjected to the brutality of child-sex tourism and used for the live-streaming of sexual acts with adults.

A woman arrested at the house on charges of abuse was their mother.

“It was horrendous,” the AFP assistant commissioner for the international operations command, Scott Lee, said.

“It was only going back a few months that we conducted a joint operation with the Philippines National Police that rescued three children from a house where they were being used to live-stream sex acts with adults. Children are being exposed to the most horrendous of crimes … it is disgraceful.”

Lee was referring to another operation involving the AFP, aided by intelligence from the FBI, which led to a raid by Philippines police to rescue three more children from a house in Cebu, the acknowledged epicentre of what is known as the “pay per view” trade in The Philippines, where children were being routinely raped and abused for the online entertainment of men in Australia and the US. The children, girls aged between 8 and 10, were forced into unspeakable acts of abuse, all streamed live via encrypted online video.

After new laws were passed to cancel passports of hundreds of high-risk sex offenders travelling to Asia — predominantly The Philippines and Indonesia — their sickening appetite has turned to the cyber underworld.

The AFP’s success in preventing pedophiles from leaving the country, and providing intelligence to foreign governments to refuse them entry, has presented a new challenge.

Lee calls it the displacement effect.

“We see more of this move into live-streaming … with people now reaching in from all over the world,” Lee says.

“It is difficult to quantify (but) there is an alarming prevalence of people accessing child exploitation material in a range of communities that you would not expect.”

According to figures supplied to The Australian, last year the AFP Assessment Centre received more than 8000 reports of child exploitation. As of September 21 this year, it has received more than 6776 reports of child exploitation for the calendar year.

To get an idea of the scale of this problem, the interventions in just two years have produced hundreds and thousands of images and videos depicting child rape, abuse and brutality.

The majority of these reports come from the National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children in the US, a not-for-profit partner of the AFP, and a member of the Virtual Global Taskforce dedicated to combating online and offline child sexual exploitation taking place around the world.

In June, parliament passed the federal government’s Passports Legislation Amendment (Overseas Travel by Child Sex Offenders) Bill 2017.

Its purpose is to prevent Australians who are “listed on a state or territory child-sex offender register with reporting obligations (a reportable offender) from travelling overseas to sexually exploit or sexually abuse vulnerable children in overseas countries where the law enforcement framework is weaker and their activities are not monitored”.

The legislation effectively makes it an offence for a child-sex offender to travel out of Australia without permission from a “competent authority”, being the police, a court or a sex offender registry.

An explanatory memorandum to the bill said that the laws were required to replace the existing regime that was having little effect on stopping Australian pedophiles travelling overseas to engage in child-sex tourism as it required police to make assessments of likelihood to offend.

“This process (was) resource intensive, being done on a case-by-case basis, and is subject to review by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. As a result, states and territories do not use these provisions at all. The measures in the bill address these constraints to protect vulnerable overseas children,” the memorandum says.

“Existing measures in Australia have proven insufficient to address the risk of overseas offending by Australian-registered child-sex offenders. In 2016, more than 770 reportable offenders travelled overseas, often without complying with obligations to notify police of their travel.”

But while the new laws refusing to allow high-risk sex offenders to travel outside Australia is a positive step, child exploitation is still a huge international plight.

A 2016 global study, Sexual Exploitation of Children in Travel and Tourism, found that “the sexual exploitation of children in travel and tourism has expanded across the globe and has outpaced every attempt to respond at the international and national level”.

Lee confirmed that the number of investigations that the International Operations unit was undertaking was growing, alarmingly.

“It just seems to be increasing across the board,” he says.

Last year the AFP shut down 80 sex tourism and online exploitation activities. Since July this year, there were another 16 successful disruptions.

“Three years ago we were averaging 20 high-risk sex offenders a month looking to travel to Indonesia or The Philippines,” Lee says.

“Over the three years where we have disrupted travel or they have been refused entry, it has gone down to three a month.”

The paradox, Lee notes, is that the prevalence of child exploitation is still growing. Like the expansion of transnational crime and terrorism, it has gone global in its networks and is increasingly using the dark web to hide.

The impact on those officers now working in the AFP’s expanding international operations command can exact a heavy toll, Lee acknowledges.

They see the worst of human nature.

“It’s not just the child exploitation, but our people in counter-terrorism that have to constantly look at traumatic online material, such as beheadings,” Lee says.

“We psychologically screen people who move in to these areas and there is an ongoing counselling process that occurs while you are in that area.

“Suffice to say you only move in there if it’s voluntary.”

THE disturbing trend in the globalisation of child exploitation is not the only target that is forcing the AFP to shift from national law enforcement to global.

Justice Minister Michael Keenan last week opened an AFP post in Mexico City to increase resources into operations seeking to disrupt global drug trafficking supply chains targeting Australia.

The volume of ice and cocaine destined for Australia that the AFP is disrupting offshore has grown to thousands of kilograms a month.

This month the largest shipment of precursor ice chemicals was seized, which, depending on the purity yet to be determined, could have produced upwards of three tonnes of ice. Already this calendar year, more illicit narcotics have been stopped beyond our borders than the total of last year, which amounted to 11 tonnes.

The globalisation of the drug syndicates and cartels means they now command criminal mini-economies worth billions of dollars.

With Australia’s demand for illicit narcotics now one of the highest in the world, Lee expects that the targeting of Australia by global networks will only increase

Lee says the joint operations that the AFP now has with China, Thailand and Cambodia were vital to shutting down the supply chains. But increasingly, transnational syndicates are setting up in the Pacific with an eye on Australia’s market.

Keenan says that increasingly the AFP would move offshore as transnational crime syndicates with global networks establish on Australia’s doorstep.

“We have seen significant seizures of methamphetamine from Mexico in Australia over the past 18 months, with links to Australian outlaw motorcycle gangs and West African organised crime,” Keenan says.

“The cocaine trade through the region is equally concerning, and law enforcement agencies in Australia continue to make record seizures.

“As a government, we have supported the AFP’s expansion of its international footprint. It is critical in cracking down on the increasingly transnational nature of serious crime. Increasingly, criminal operatives know no boundaries and we have to attack this head-on.

“The AFP has a unique and extensive international remit and operates one of the largest and most diverse law enforcement international networks. This has allowed the AFP to take the fight against crime offshore to the very place it originates, or the places it transits through.”

The first AFP overseas post was established 44 years ago, in Kuala Lumpur, to combat what was then the trafficking of heroin into Australia.

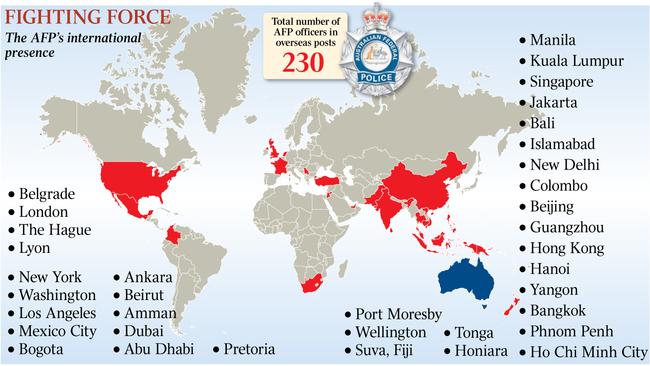

Today there are 230 officers based in posts as far afield as Europe, Britain, the US and Middle East. They are based in embassies, liaison posts or embedded in the local agencies of foreign countries in 36 cities outside Australia.

The largest contingent, not surprisingly, is centred in Southeast Asia.

The functions, which range from intelligence to joint operations on the ground, cover every imaginable crime, from kidnapping of Australians abroad, child exploitation, transnational drug trafficking, global money-laundering syndicates, human trafficking and investigating murders of Australians overseas.

Regional security deployments into countries such as the Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea and East Timor have also seen the expansion of AFP resources abroad.

But counter-terrorism has seen the most rapid international expansion of Australian policing resources.

The 2002 Bali bombing changed everything for the AFP.

Lee headed up the AFP’s counter-terrorism unit sent into Indonesia following the Bali nightclub bombing at Kuta Beach, which killed 88 Australians.

“It was certainly a challenging period for us as an organisation in terms of the response to that first Bali attack, particularly when you look at the scale of the mass casualty attack on our doorstep,” Lee says.

“For me, it was … I think what you are always struck by was the responsibility you had, particularly to the victims and the victims’ families.

“One family member said to me at the end of the day, their child had passed away after the attack, they actually said that what had helped them get through the grieving process was knowing that Australia was assisting and working as part of the investigation.

”It helped with the grieving process in terms of victim identification, returning loved ones to their families, but also the work we did with the Indonesians to bring people to justice.”

Lee, who began his career with the AFP’s Victorian operations during the underworld violence of the early 1980s, says the terrorism threat had become the AFP’s key priority for the international operations.

Since the Islamic State declaration of a caliphate in 2014, the AFP’s counter-terrorism role has rapidly expanded into the region.

Counter-terrorism units, based in Turkey, Indonesia and now also in the southern Philippines, which has become the new beacon for Islamic extremists, have become critical to Australia’s offshore defences against the flood of foreign fighters, predominantly Islamic State and al-Qa’ida combatants, attempting to return to the region.

In the past 15 months, the AFP has been involved in disrupting six planned terrorist attacks in the region, predominantly Indonesia.

Lee’s sober assessment suggests that despite the extraordinary successes in preventing terror attacks, netting sex offenders and disrupting the global supply chains of drugs, the prevalence of criminality is only increasing and becoming more globalised.

Some of these operations have become so sophisticated that they are operating like multinational companies using the same trade and commerce routes that have delivered economic benefits to Australians, Lee says.

“It adds another level of challenge. I expect that it will continue to grow.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout