Drawn to defy demons

BAY Rigby left behind a guide to dealing with bipolar disorder.

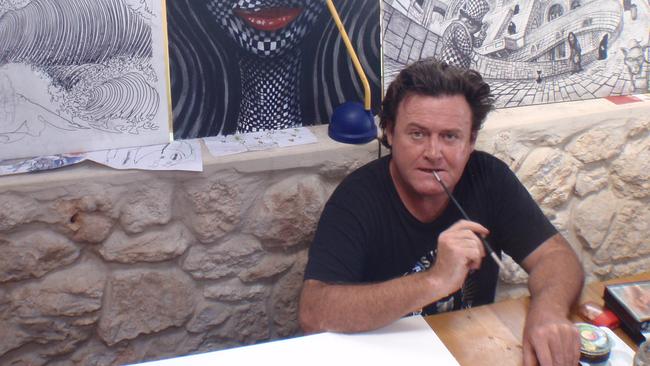

BEFORE he’d reached his sixth birthday, Bay Rigby discovered he could draw an image of his brother Peter in perfect perspective.

“I remember him scribbling on butcher’s paper, saying to me, ‘I can draw now. I can draw you from any angle I like,’ ” says Peter. “And he could do it — Bay was a remarkable talent.”

In the months before he died in 2011, aged 48, Rigby worked feverishly to illustrate a small book called Shrinking the Shrink. The pictures emerged as fast and fluently as they had in his heyday as the New York Post’s cartoonist. But the subject matter was wry, acutely wrought and intensely personal; Rigby was illustrating the causes, experiences and treatment aspects of mental illness.

Among the images is a bug-eyed baby sitting alone in a corner, representing neglect and abuse; in another, a closet door opens with skeletons piling out and “Family History” written on the door. In a third, a psychiatric patient tethered to a ball and chain scratches the days of his “sentence” on a wall.

For the book’s cover, Rigby drew a brain with legs that was running through a maze. Underneath the image are the words: “A Simple Road Map to Recovery”.

He collaborated on the book with his friend, doctor and fellow bipolar sufferer John McAuliffe.

“We had a three-month period when we saw each other daily,” says McAuliffe, a practising GP in Fremantle.

“It was wonderful; he’d arrive about 8am and wouldn’t leave until 10pm. He was always such a big personality — a real bipolar.”

Three and a half years after Rigby’s death from an accidental drug overdose, the pair’s little book is seeing the light. Earlier this month, a draft version was handed around at mental health forum Meeting for Minds, which brought together neuroscientists, researchers and clinicians from Australia, Israel, France and Switzerland in Fremantle to converse with sufferers and their families about the lived experience of mental illness.

Their premise was that treatment for mental illness had stalled in the past two decades, and that clues to new therapies and preventive strategies could emerge from a dialogue that included those closest to the illness.

The experts — who include Norman Sartorius, former director of the World Health Organisation’s mental health division, and Ian Hickie, director of Sydney’s Brain & Mind Research Institute — may have been taken aback by the pared-back approach of Shrinking the Shrink.

Lively cartoons illustrate small nuggets of advice about self-care, connecting with the community, taking exercise, accepting that noncompliance with treatment is the leading cause of its failure.

There are even quirky entries under “Coitus” and “Creator”: “There are unanswerable questions about your worth and the meaning of life. Is there an omnipresent non-interventionist higher power?”

McAuliffe describes the eccentric and at times funny book as a self-analysis tool that aims to be especially accessible for young people.

WHO research indicates more than 40,000 young Australians are likely to develop mental health conditions in the next six years, and it’s likely to show up first between the ages of 15 and 21.

“Bay believed, and I still believe, that the way forward for mental health is prevention and early intervention. If you are going to understand and beat the wave of depression that is hitting societies worldwide, you have to get in early,” McAuliffe says.

“I believe this sort of stuff should be compulsory on the school curriculum.”

It never figured in Rigby’s curriculum; by all accounts he was too busy surfing, playing state-grade football, doodling and drinking steadily from age 14.

His talent as a cartoonist and artist blossomed early, inherited from his famous father, Paul Rigby. The latter was arguably Australia’s most prolific and renowned cartoonist, a recipient of an Order of Australia for services to cartooning.

Paul Rigby’s career had taken him from Australia (where he won five Walkley awards) to London, where he worked on two of Britain’s largest selling publications, The Sun and News of the World.

Moving on to New York at the personal urging of News Corp chief Rupert Murdoch, Paul Rigby produced 15,000 daily cartoons while working for the New York Post; he was a four-time winner of the New York Newspaper Guild’s prestigious Page One Award.

Meanwhile, Bay Rigby was showing precocious talent in his job at The Boston Globe. Then came a job offer — also from Murdoch — that saw him pitted against his own father in an extraordinary interfamilial rivalry.

“When Dad took a better-paying job, literally up the street at the New York Daily News, Rupert Murdoch rang Bay up and said, ‘Do you want your dad’s job?’ ” recalls Peter Rigby, who was also working in the US at the time.

“Bay was 21 and was being offered a job to cartoon for 14 million New Yorkers, six days a week. He would have been under a lot of pressure.”

Bay Rigby served as editorial cartoonist for the New York Post from 1984 to 1992; like his father, he won four Page One Awards. As a consequence, Sunday lunch gatherings in the Rigby expatriate household took on a mildly competitive air, Peter Rigby recalls.

“Dad and Bay would use the same drawing board at home to get their cartoons out for the Monday editions of their respective papers,” he says.

On occasion, Peter noticed scribbled comments down the side of the drawing board paper, in which father and son poked fun at each other’s latest work.

“Even when they were hammer-and-tongs in competition, I never saw any serious hostility,” he says. “They both loved the adulation, the parties, all of it.

“Bay became a skilled artist almost by osmosis, while Dad really practised his art. I think Bay was the more natural artist, but Dad was more disciplined.”

The father-and-son trajectory couldn’t have been more different; while Paul Rigby produced cartoons, paintings and illustrations until his death in 2006, Bay’s career path was punctuated by bouts of heavy drinking, depression and suspected bipolar disorder.

His performance at work became erratic and jobs were forfeited; more than once, on two continents, Bay found himself busking on the streets and befriending other homeless people.

Louise Horwood, Bay’s partner during his last two years, remembers him asking politely at a country hotel for the fire to be lit since his friends were feeling cold. “After his third request, when nothing happened, he took it upon himself to burn the wood basket,” she says.

“He was dealing with demons and he characterised them as demons. He would recognise the duality of his condition, and it was a challenge that he faced. But his incredible talent and his illness were two different things. People couldn’t get past his dad, who was so well known and loved.

“Bay got a bit lost in all that. His father had told him ‘You’re just like me’, and he got a lot of satisfaction with that.”

Peter Rigby suspects his brother’s early history of drinking “became a crutch for the rest of his life”. “He began to have highs and lows in his 20s, which is quite daunting when you think of the binge drinking that goes on now among teenagers,” he says. “He shouldn’t have touched alcohol and drugs, and then he might have been OK.”

Bay was diagnosed as having bipolar disorder, previously called manic depression, in which people experience manic highs as well as periods of clinical depression. Only one or two in 10 people with depression have bipolar disorder.

The Meeting for Minds forum has explored why research “has failed in recent decades to improve dramatically the lives of most people living with major mental illness”. There has been tentative exploration of alternative hormonal, neuropeptide and immune therapies during the past decade.

“However, none of these approaches has moved into mainstream use for those affected by the major psychotic or mood disorders,” Hickie says.

Among those speaking as “consumers” was McAuliffe. His empathy for his friend Bay did not come from bedside consultation. McAuliffe has endured a dozen episodes of hospitalisation and sessions of electro-convulsive therapy, between periods of good health.

“I’ve been in 12 times, in seven different hospitals in Perth, and I’m yet to see a clinical psychologist,” he says. “You don’t get any counselling, even as a private patient. You’re given a pill or ECT and left to fend for yourself.

“If your behaviour improves and you’re not causing any trouble, then you go home.”

McAuliffe says he and Rigby strove to convey a simple series of messages to sufferers of mental illness, with the cartoons aimed at engaging the reader and blank sections for individuals to write their own thoughts and conclusions.

“I’ve been giving the advice in the book to patients for 20 years,” says McAuliffe, who is an ambassador for mental health body Beyondblue. “We’ve condensed whole textbooks into 30 pages of text and Bay’s cartoons.

“The idea is that the book can be read in a matter of minutes by anyone feeling confused about being in a psychiatrist’s office, or even in a GP’s surgery. They can pick it up and say, ‘That relates to me a bit.’ And the pictures tell a thousand words.”

But he says treatment is a combination of medication and good advice, a message that Rigby ultimately failed to heed properly. “You don’t treat bipolar, severe depression and psychosis with mere chitchat,” says McAuliffe. “You need to medicate and you need a framework in which to recover.”

On July 17, 2011, a few days before he died, Rigby posted a message on Facebook lamenting the death of his high-spirited friend David Ngoombujarra. The 44-year-old actor, who was featured in a small role in Baz Luhrmann’s film Australia, had been found dead in a park from a drug overdose. A week later, on July 29, an unconscious Rigby was found with a needle in his arm in a warehouse studio lent to him by a friend. An ambulance was called, but it was too late.

In his final months, Rigby asked his partner Horwood to scan and upload on to the internet all his drawings and paintings. “He insisted on it,” recalls Horwood. “He wanted the body of his work to be enjoyed by a wide variety of Western Australians.

“The day he died I spoke to him a couple of times, and he sounded calm and happy, poised to have another exhibition after an incredible outpouring of work. He’d spent the morning with John (McAuliffe) and his son in Fremantle, going to toyshops.

“Perhaps in a manic state or feeling invincible, he’d got cash from the sale of a painting and blown it on drugs. It was just a mistake; Bay wasn’t wretched, he loved life.”

The international mental health forum Meeting for Minds will reconvene in 2016. meetingforminds.com.au