Cracking terror’s codes is becoming increasingly difficult for governments

Terrorists are exploiting messaging app encryption, creating a dilemma for authorities battling to prevent attacks.

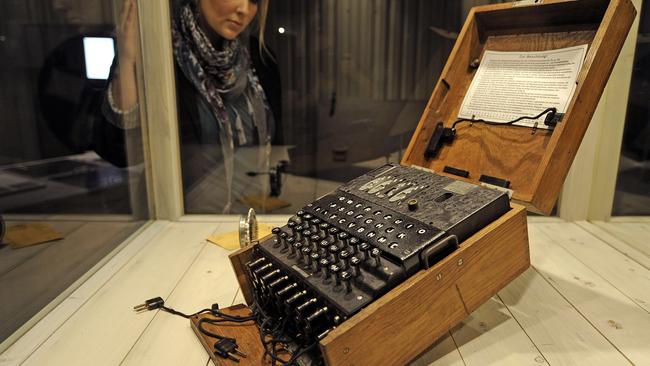

Who wasn’t moved by the story of Alan Turing, the brilliant English mathematician whose dedicated team cracked the Nazi Enigma code and saved countless lives during World War II?

Fast forward more than 70 years and the ability of terrorist groups such as Islamic State and al-Qa’ida to harness encryption methods on the internet has created its own Turing doomsday imperative. Either we crack the codes or our law enforcement agencies will remain in the dark about terrorist plans for more carnage.

Next week, political and national security chiefs from Australia, New Zealand, the US, Britain and Canada will meet privately in the Canadian capital, Ottawa. High on the agenda will be ways to combat terrorism, and one of the key points will be cracking encryption in messaging apps.

The task at this conference, known as Five Eyes, is incredibly difficult — nearly impossible. (This is discussed in the second half of the video below.)

Some of the most common messaging apps are Apple’s iMessage, Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram and Wire. Every day, millions of people send billions of messages to each other, secure in the knowledge that new-age encryption technology means their conversations will remain private.

But terror cells are exploiting encryption technology, creating a dilemma for political leaders and intelligence chiefs battling to monitor their conversations and prevent new attacks. Two years ago Joe Hall, chief technologist at Washington’s Centre for Democracy & Technology, told business news channel CNBC that Islamic State devoted a division of its commanders to educating sympathisers and members on how to use encrypted communications.

However, any move to allow intelligence agencies greater power to bypass encryption raises huge privacy concerns and risks undermining public confidence in messaging apps used by millions of mostly law-abiding citizens.

There is growing pressure on some of the world’s biggest technology giants that own the most popular messaging apps to play ball with investigators and work together to combat the issue.

That applies also to start-ups. Take Telegram, the brainchild of Russian brothers Pavel and Nikolai Durov. The brothers are also founders of VK, a Russian equivalent of Facebook.

Telegram has been popular with terrorists. Two years ago, Telegram shut down 78 Islamic State-related groups at the time of the deadly Paris attacks, but Islamic State didn’t go away. Reports also suggest Islamic State released encrypted messages in Telegram to call for this year’s lone wolf attack on Britain’s parliament, Westminster.

The idea of helping authorities is a sensitive issue for Pavel Durov. He exiled himself from Russia after he was ousted as Vkontakte CEO, having refused to hand over details of Ukrainian protesters to Russia’s security agencies.

But Telegram does offer some assistance against ISIS. On Twitter Telegram says that every day it blocks more than 60 ISIS-related channels, more than 2000 channels each month. But it’s the secret chat feature with end-to-end encryption that probably has authorities concerned.

In an interview with online technology publication Engadget, Pavel Durov was asked if he slept well at night knowing that terrorists used his platform.

“I think that privacy, ultimately, and the right for privacy is more important than our fear of bad things happening, like terrorism,” Durov said. “But ultimately, the ISIS (Islamic State) will always find a way to communicate within themselves. And if any means of communication turns out to be not secure for them, they’ll just switch to another one.”

Encryption code is a free, open source, online for all to download and use. These days anyone can own a software-based version of an Enigma machine and there are probably millions out there.

The most popular method raised by cyber experts as a way of bypassing encryption codes is known as a backdoor, a code inserted into a messaging app that lets law enforcement override the encryption. But backdoor codes can become security risks themselves. The outcome could be deadly if cyber criminals, terrorists or rogue states discover and exploit these backdoors to decipher confidential conversations.

The hacking of malicious software tools stolen from the US National Security Agency shows information kept by law enforcement can be stolen and used against them. Hackers drew on those tools to execute the WannaCry ransomware attack last month that infected computers across the world. Give law enforcement a backdoor into encrypted software and hostile states may try to use those backdoors for commercial or military gain.

Then there are the tech giants, Apple, Microsoft, Google and Facebook, and developers of the messaging apps. They don’t want to be saddled with compromised security offerings.

In 2015, Apple opposed an FBI order to unlock the iPhone of Islamic State gunman Syed Rizwan Farook who, with his wife, Tashfeen Malik, murdered 14 people in San Bernardino, California. The FBI later said it had unlocked the phone itself.

But times are changing. Apple chief executive Tim Cook has told Bloomberg the tech giant is co-operating with the British government after the terror attacks there. That was after the government went through “the lawful process”, Cook says.

When it comes to encryption, Australian Attorney-General George Brandis — who will be attending next week’s Five Eyes meeting with Immigration and Border Protection Minister Peter Dutton and the country’s key intelligence chiefs — is treading carefully. On the one hand, he says the Turnbull government is considering law that requires social media companies to work with government agencies to decrypt communications. But Brandis is ruling out a backdoor approach.

Brandis has told Sky News the federal Crimes Act and Telecommunications Act don’t go far enough in imposing obligations of co-operation on corporations. “In the first instance, the best way to approach this is to solicit the co-operation of companies like Apple and Facebook and Google, and so on, and I think there has been a change of the culture in the last year or more,” he says.

The job is harder because of end-to-end encryption, where a message is encrypted from the time it leaves a user’s device until it is decrypted by the receiver. Only the sender and receiver can unravel the code, so it’s no good asking an internet provider, app maker or telco to decrypt them. Only the receiver has the key.

While some encryption methods can be cracked, unravelling encryption codes that are 256 binary digits long is regarded as nearly impossible.

It has been said that this encryption method generates more key combinations than there are atoms on Earth, and that cycling through each key option to find the decryption key would take as long as the age of the universe.

So if you can’t hack the encryption method, you might hack into terrorists’ phones and read messages before they are sent, or after they are decoded, or access unencrypted backups.

Monash University software engineering lecturer Robert Merkel says agencies could secretly install software that forwarded messages to them before they are recoded or after they are decoded.

There is another way. In commonly used public key cryptography, the sender wraps a message in what’s called the public key of the recipient. The receiver then has a matching private key that can decrypt messages. It’s like a bank safe that requires two keys to open it: here the messages need two matching keys to be read.

In this scenario, app makers can conceivably circulate a crooked version of a messaging app that wraps messages with a recipient’s public encryption key and the public key of law enforcement. Law enforcement could use their private key to read the message. The authorities have two keys to the safe. In this way, the encryption algorithm itself isn’t compromised but the app’s operation is.

Merkel says it is possible sophisticated encryption already has been compromised and the agencies are not telling us. If they did, the terrorists would stop using that encryption.

“There is always the possibility that intelligence agencies have found weaknesses in some of those (encryption) schemes that haven’t been publicly revealed,” he says. “They could be keeping this secret for the reason they want to use that knowledge to get access to high-value communications.

“Once it (the compromise) becomes public, particularly if there are details of how it’s done, the encrypted messaging app is not longer of use to anyone.”

But he says it’s unlikely end-to-end encryption apps are cracked. He says messaging apps such as WhatsApp and Signal use a combination of encryption methods and consequently both are regarded as “unbreakable”.

But he says if governments had app makers agree to a backdoor exploit, and this became known, it would be “a trivial matter” for terrorists to build their own encrypted messaging apps. This could lead to an internet where terrorists are the only people who could send and receive truly secure messages, while the apps the public uses are compromised.

There is also the constraint of Australian law. While there are legal restraints on how authorities here can use a backdoor, a foreign power can exploit it once they know about it. “Any legal protections against arbitrary accessing of an individual’s private data don’t apply to foreign governments,” says Merkel.

Australian Computer Society president Anthony Wong says it is hard to see how one could break encryption messaging without using a backdoor: “But the use of backdoors in hardware or software creates its own menagerie of problems, not the least of which is the abuse of the backdoor by criminal or terrorist elements once the backdoor is exposed,” he says.

Wong also warns forcing corporations to compromise their messaging and communications systems — as proposed by Brandis — could send terrorists further underground.

“The ACS is a strong advocate of individual privacy and while we agree on the need for closer co-operation between government agencies and technology companies to help prevent terrorist threats when possible, forcing companies to assist in decrypting messages, when it’s viable, and often it won’t be, is likely to only push terrorist communication further underground, using other encrypted communication tools by foreign companies not bound by this or similar legislation here or overseas.”

Intelligent Business Research Services adviser James Turner says no right-thinking person wants to make life easier for terrorists, organised criminals and pedophiles.

“At the same time, the genie is out of the bottle. If any government pushes for a backdoor to any communication app that people are using now, the adversaries won’t use those technologies because they will find out about it,” he says.

He says terrorists track the media and will know that legislation has passed and the government has been leaning on vendors. They’ll stop using that product and so will the public.

Turner says cybersecurity is becoming a barbecue conversation topic. “All it takes is for one person to say ‘I wouldn’t recommend using that, use this one instead’. Any vendor that gets pressured to start debilitating its own product is quickly going to find itself running out of customers.

“In an environment where really good encryption is common, the intelligence agencies are going to have to work much harder and be much more focused. That’s going to get expensive for them.”

Or course, things can change. As computing systems get more powerful, the prospect of cracking encryption improves, says Turner.

“The computational power that we use to crack these things is continually getting better and once we’ve got quantum computing fully up and running, the problems that we previously thought were unsolvable could conceivably be very simple.”

But things remain difficult for the intelligence community.

“The intelligence agencies are coming out of a golden era where they were able to intercept the entire lot of communications going everywhere. That’s part of a chess board that they’re going to have to work around,” Turner says.

Whatever the world’s top political leaders and national security chiefs decide at Five Eyes next week, it mostly will be kept under wraps. Tipping off the terrorists is no option.

After the Enigma code was cracked, some decrypted lifesaving intelligence wasn’t passed on to the frontline because it risked tipping off the Germans that the code had been cracked.

Five Eyes might succeed in reining in some encrypted terrorist communications by less tech-savvy Islamic State followers who use compromised everyday messaging. But there is always a fear the most technology-capable terrorists will remain a jump ahead.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout