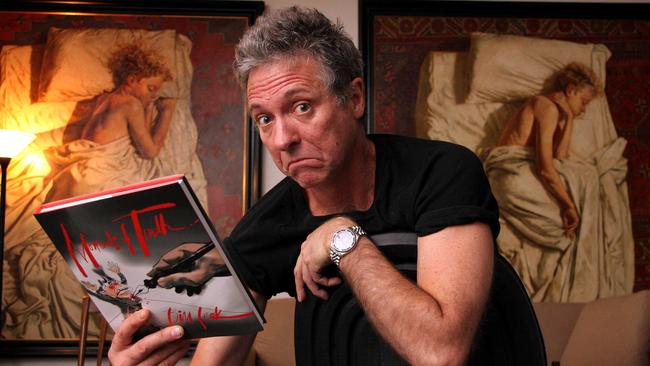

Bill Leak obituary: the people’s choice

Bill Leak didn’t so much fear death as worry that he wouldn’t have lived enough.

Bill Leak didn’t so much fear death as worry that he wouldn’t have lived enough. In particular, that he wouldn’t have created enough.

“There’s a certain urgency about the creative process,” he wrote a decade ago. “Whether it’s painting, writing, making music, or whatever, the important thing is that it’s got to ‘come out’. The last thing I want is to go to the grave thinking about cartoons or paintings I never got around to doing.”

In a life often lived at the edge, Leak was more than once at risk of going to that grave, though the late 2008 balcony fall at adman John Singleton’s place that famously almost killed him was yet to happen.

In the same piece of writing he described one near-death experience as being one where “far from experiencing some kind of spiritual epiphany, all I experienced was a deep anger directed at myself for having spent so much time propping up bars when I should have been ‘getting them out’.”

He needn’t have. Leak died of an apparent heart attack yesterday, aged 61, the winner of two News Corp awards for cartoonist of the year, nine Walkley awards for excellence in journalism, 19 Stanley awards from the Australian Cartoonists Association and 12 times as Archibald Prize finalist. He was called the best artist never to win the Archibald, although he won the packing room award twice and once the people’s choice.

It is common to describe someone on their death as having crammed more into one lifetime than others might in several. In Leak’s case that is true, a fact made doubly cruel by how short it was cut. Elite-level pianist, author, master raconteur and prolific swearer, he described his obsessive personality as “a gift rather than a malady” and told a psychiatrist who promised to get him “back on the straight and narrow” that there were two things he’d always hated about that idea: it was straight, and it was narrow. Fine tributes flowed, from the Prime Minister down, at news of Leak’s sudden death — as was proper, since even Malcolm Turnbull counted him as a close friend. At the South Australian press club when the news was announced, ahead of an address by renegade senator Cory Bernardi, there were audible gasps.

But it was the anecdotes told of him at close quarters that really illuminated an energy capable of somehow appearing to be both uncontained and sharply aimed.

Strewth columnist James Jeffrey recalled starting at this newspaper years ago when Leak still worked in a studio in the Sydney bureau, yet to make the migration to his NSW central coast retreat.

“Once he showed me his letter of response to someone who’d complained about his ‘gross disrespect’ to John Howard,” Jeffrey said. “I can’t remember who it was, but I remember the tone of the complaint: semi-important and totally pompous.

“Anyway, Bill’s letter went something along the lines of: ‘Dear Mr so-and-so, your generous offer of your daughter’s hand in marriage interests me greatly. Please send a photo. Here’s one of me.’ And the photo was of Bill grinning at the camera while crouching before one of his more scabrous Howard cartoons and giving it the finger. ‘What do you think?’ Bill asked. I believe he posted it later that day.”

For Leak there were two primary drives perhaps above all else: an undying loyalty to friends and colleagues, and a belief in the cartoonist’s craft as being one of exposing hypocrisy and pricking pomposity. In both cases absurdity was an extra, rarely optional.

He had a business plan for cartoon covers to slide over cigarette packets, hiding their gruesome images of disease. He was a cryptic crossword nut but he took forever to complete them because there were so many other conversations to be had at the same time, such was the pace at which his mind ran. And he was an inveterate practical joker, engaging in a long-running battle with The Daily Telegraph cartoonist Warren Brown in which Leak so often seemed to come off the loser. Fred Pawle, a surfing writer at The Australian and a close friend of the cartoonist’s two sons, Johannes and Jasper, said Leak had learned to draw during a rough public school childhood in western NSW and then Sydney “as a way of ingratiating himself with the bullies by making caricatures of the teachers”.

“He had to learn pretty young to defend himself because his name was Willy Leak — so with a name like that in a rough public school, it was either be bullied or stand up,” Pawle said. “But Bill only ever saw things from the perspective of the average bloke. He taught me that no one’s above everyone.”

Pawle and the three Leaks spent years surfing together, a sport Bill Leak had returned to in adulthood in part to stave off the depression-fighting booze he spent years in an on-and-off relationship with, the past few of them sober. The problem was, though he loved getting out in the waves he never really rated his surfing style, referring disparagingly to the “skeleton” stance he adopted at his then home break of Bondi. In fact, Pawle said, “he would look out the window from his apartment, and if it was particularly small and uninviting, he’d yell, ‘Billy would go!’ ” — a reference to big-wave Hawaiian legend Eddie Aikau and the surfing catchphrase of the time that defined fearlessness: Eddie would go.

It was typical Leak self-deprecation; he did not define the capacity of a person by their fear or lack of it but by their willingness to critically engage with the world, a tendency perhaps sharpened at least in part by that long encounter with depression.

Bemoaning the increasing inability of society to get a joke, Leak wrote in this newspaper last year that the drift towards an all-encompassing political correctness, with “sanctimonious hordes lying in wait” online “ready to ambush anyone who transgresses the unwritten laws of the new puritanism” meant the cartoonist’s job “gets harder every day”.

“The trick has always been to look at a serious issue, exaggerate it to the point of absurdity and draw what you see when you get there,” he wrote. “But the trick doesn’t work in these strange times when the more ridiculous an issue is, the more seriously it’s taken. And if you’re starting at the point of absurdity, where do you go from there? What’s the point in pointing out the absurdity inherent in something that’s obviously absurd and, more important, why isn’t everyone already laughing?”

He had no problem with being a champion of the left during the long Howard years, but then being convinced by the failures of the Rudd-Gillard governments to move to the right. The truth of the matter was, he said, that “freedom of speech is the freedom to offend, and that means the freedom to offend anyone”.

Leak most recently has been associated with the campaign against section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act, his cartoon last year depicting a deadbeat Aboriginal dad prompting a case against him in the Australian Human Rights Commission that was later dropped. Giving evidence last month to the parliamentary inquiry into 18C, he declared the law should be changed because “if you’ve got an agency of the state hauling someone over the coals for telling the truth, you’ve obviously got a problem with the law”.

But Leak was so much more than just the 18C debate and, in any case, he made a long career out of offence — even when he was prepared to apologise to his targets, as he did to Howard-era immigration minister Philip Ruddock at an event just last year. Whether he ever sought Alexander Downer’s absolution for depicting him at every opportunity in his fishnet stockings is another matter. Leak’s 2006 cartoon depicting an Indonesian as a dog mounting a West Papuan, published at the height of the diplomatic scrap when Australia granted refugee visas to 42 Papuans who had arrived by boat, caused international ructions.

The Indonesian character, ostensibly president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, though Leak always tried to insist it wasn’t, was pictured saying “don’t take this the wrong way”, with the caption reading “no offence intended”. It was prompted by a cartoon in Indonesian tabloid Rakyat Merdeka depicting John Howard mounted on foreign minister Downer, saying: “I want Papua!! Alex! Try to make it happen.”

“I wasn’t trying to provoke a situation and I wasn’t trying to do anything that was going to be deliberately damaging to our relations with Indonesia,” he said at the time. “I was trying to make a point and I was trying to make it in a humorous way, and if someone out there doesn’t get the joke then I can’t really be held responsible for that.”

Nor was he trying to “provoke a situation” when he turned his attention to Islamist terror and ended up in a high-security nightmare. His cartoon in response to the Charlie Hebdo massacre in January 2015, featuring an image of Mohammed, was apparently so offensive to Islamic State members fighting in Syria that they issued a fatwa against him, calling on “fellow mujaheddin” in Australia to hunt him down and kill him.

As a result he was forced to move house and live under extreme security measures, unable even to tell stepdaughter Tasha what was going on. He and his family, he said later, were being terrorised and there was no doubt Leak felt the stress keenly.

Despite that, in recent years Leak had begun for the first time to really find “happiness without any anguish” according to Pawle.

“He was truly satisfied for almost the first time in his life with what he’d achieved and the man he’d become. Until then there was always an element of anguish and uncertainty about him.”

Leak is survived by his wife Goong, sons Johannes and Jasper and stepdaughter Tasha.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout