Barnaby Joyce’s affair with a staffer needed to be made public

Midlife crisis, drunk on power or just a man in love; Who knows what led Barnaby Joyce to this point? But we paid his bills.

There are some writers whose bylines are worth searching out because whatever they write will be worth reading. Our own James Jeffrey is in that category.

Jeffrey is a complex man: he’s a husband and father; a player of bagpipes; a keeper of snakes; a survivor of a chaotic childhood in a broken home. A Dylan fan, of course, whose memoir comes out later this year. But we’re not here to talk about him. We’re here to talk about the people he writes about during sitting weeks in Canberra — which is to say, we’re here to talk about politicians and how they, too, are actual people.

Jeffrey’s The Sketch column in The Australian does not exist to analyse politics or even policy. It exists to remind us that politicians are human, with all the unfit frailty that entails. And what an assignment he had this week.

As everyone knows, one of our key politicians — the ruddy-faced Nationals leader Barnaby Joyce — has been playing an away game. A young woman once employed by him — and therefore by you, since we all pick up the tab — is expecting a baby, his fifth.

Joyce has separated from his wife, Natalie, and has moved out of the home he shared with his four daughters.

In composing his column, Jeffrey could have gone the comical route: Barnaby-the-bonker, now expecting a barn-a-baby, and all that. Instead he sat down and he watched, and calmly described the scene in Parliament House as the embattled — such a handy word in this instance — Joyce took up his seat for his first question time post-revelation.

All eyes were on him, and that was even before he got up to speak, which Joyce really had to do because if you just sit there and don’t say anything, the story doesn’t go away.

It gets bigger.

And so Joyce rose.

“And as he did, a peculiar thing happened,” wrote Jeffrey. The House of Representatives — a catcalling house if every there was one — fell silent. For here was a man wholly exposed, standing utterly vulnerable to anything that anyone might throw at him, even literally.

“He looked the very picture of a man who could, off the top of his head, think of — ooh — at least 50 dozen places he’d rather be,” Jeffrey wrote. But also, crucially, like a man whose head was dancing — yes, dancing — with “the exciting uncertainty of the life ahead of him, and the shards of the life he has left behind”.

And doesn’t that capture it perfectly?

Yes, Barnaby Joyce is the Deputy Prime Minister, a man held to a higher standard of behaviour by virtue of his position, and indeed because of his own public statements, but he is also a human being and therefore fallible.

Who knows what led him to this point? Maybe this is a midlife crisis. Maybe it’s something worse than that: maybe he’s an ego on legs, drunk on power and indeed on alcohol, who thought he could have his cake and eat it too.

Maybe he really did just fall in love.

The question this week has been how much we — the poor punters paying the bills while all this goes on — needed to know about what he was doing after the lights went out.

Some journalists, mainly from Canberra, have been arguing for silence on the matter, which is curious. Uncovering is what they’re meant to do. The logic of their argument, as far as it could be followed, was that affairs between politicians and their staff — or journalists — are “private” or else “not in the public interest”.

That may be right at times, perhaps even most of the time, but not in this case.

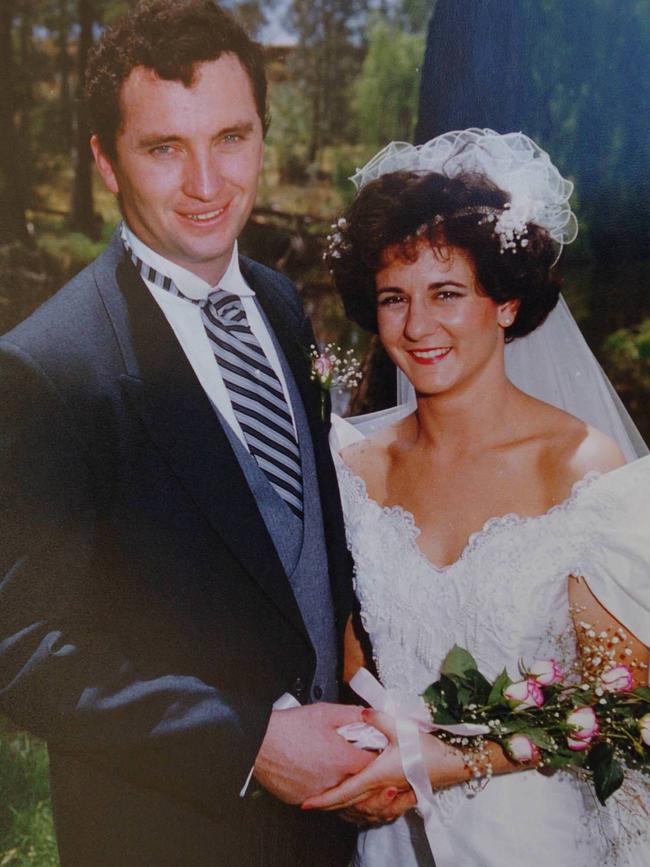

Joyce is a key member of Malcolm Turnbull’s team. He spent much of last year campaigning against same-sex marriage — which is to say, pontificating on the sexual and human rights of others. Also last year he was declared a dual citizen and had to fight to regain the seat of New England, which the Turnbull government needed to hold because it only has a one-seat majority. He has long campaigned as a conservative family man with traditional values. His wife Natalie and his four daughters featured in a magazine spread in this very newspaper ahead of polling day.

Joyce is now expecting a baby with Vikki Campion, 33, a former News Corp journalist who started working as his media adviser in 2016. She soon became much more than that, which isn’t meant to insinuate anything.

She understood social media and journalism and she was a good sounding board. They started texting and calling each other dozens of times a day. Rumours of an affair began to spread, encouraged by those employed to practise dark arts in Canberra, because that — rumour-mongering — is also one of the ugly things that happens on the hill.

Attractive women get brought down by slurs and innuendo. Who can forget how they tried to do it to Peta Credlin, despite the fact that in her case the rumour wasn’t even remotely true?

But maybe in this case it was true?

The former member for New England, Tony Windsor, who loathes Joyce, certainly thought so and did his best, via Twitter, to spread the gossip across the land. At some point Mrs Joyce heard it and began to believe it, and by the time the by-election came around, pretty much all of New England was talking about it.

But nobody reported it.

Why not? Well, that bone has been well and truly chewed this week. No question, it’s difficult to stand up a story about sex when the two parties are denying that sex happened. In truth, most reporters weren’t inclined to try. The Daily Telegraph’s Sharri Markson — a relatively new arrival in Canberra and still an outsider in that she flies in and out, as opposed to stewing in the soup there — disagreed, for all the reasons listed above: one of Australia’s most vocal campaigners for traditional marriage had left his wife for his pregnant girlfriend, who had previously been a junior employee on his personal staff.

Surely the public had a right to know?

Markson wrote a yarn last October that said as much as she was able to stand up: Joyce was battling “vicious innuendo” as he tried to hold his seat. Fellow members of the Canberra press gallery took umbrage on Twitter, again suggesting it was nobody’s business. Behind the scenes, the Turnbull government was working hard to keep a lid on the story. Questions were denied or went unanswered. Formal freedom of information requests that might have revealed, for example, how often the couple travelled and dined together were rejected. Joyce won New England on December 2 and resumed his cabinet posts the same day.

Five days later he told parliament his marriage was over, acknowledging that he was “not any form of saint”.

Did he think that would be the end of it? Maybe, because summer came and went but the story wasn’t going anywhere. How could it? Campion was pregnant. At some point, Barnaby would be spotted, as the Telegraph’s editor, Chris Dore, so nimbly put it this week, pushing a pram around Lake Burley Griffin.

Was the press gallery going to ignore that, too?

Incredibly, there are still some people who think Markson should have left the yarn alone. But by far the most vocal group in the wake of this story breaking is the one that can’t believe the information was kept from them, especially ahead of the by-election. Nobody wants to be kept in the dark and fed manure, not by the politicians and especially not by the media, whose business is not to decide but to report. Add to that the group that feels intense anger on behalf of Natalie Joyce, who has declared herself devastated, and the group — mainly women — who are furious about the double standard because, 100 per cent for sure, if Joyce were a conservative female politician in her 50s who had an affair with a 30-something staffer in her office, and who then fell pregnant and left her husband — oh look, on any one of those points, she’d be gone.

Joyce isn’t gone. He will recover. Indeed, he already has, telling Leigh Sales on the ABC’s 7.30 on Wednesday night that he felt “incredibly hurt” that his private life has been thrown into the public arena and that he “can’t quite fathom why basically a pregnant lady walking across the road deserves (the) front page”.

Please.

This was always going to make the front page, and Joyce, being the protagonist and ostensibly the gentleman, should have taken control of the situation long ago, if only to prevent his “pregnant lady” from being snapped in her sneakers on a run to the shops.

Also because five other women — his estranged wife, his four daughters — are also directly and publicly affected.

And the baby. The baby is affected, too.

As for what happens now, independent MP Cathy McGowan has suggested having “a conversation” about fraternisation in Canberra. “The parliament is a place of work and good workplace practice includes clear expectations about behaviour,” she said.

In reality, it’s no different from any other workplace. People flirt and date and sometimes fall in love. They get married and have babies and then come the affairs, the separations and, sometimes, love anew. How does anyone even try to police that? The heart wants what it wants and you can change that like you can change the tide.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout