A make or break gamble

RUPERT Murdoch knew the major challenges in publishing a national daily were technology and logistics.

THE journalists and sub-editors sat slumped around the newsroom floor, their faces etched with relief and exhaustion. They had wrapped themselves in heavy coats and scarves because the office heating was too weak to ward off the icy Canberra evening outside. Around their feet lay a small ocean of discarded paper because in all of the frenzied anticipation of this historic night of July 14, 1964, someone had forgotten to order wastepaper baskets.

“It was a night to remember, or so we were determined to think, especially after the third celebratory drink,” the late James Hall, who helped to sub-edit the paper’s inaugural edition and would later become its editor, recalled in 1996. “But those of us there couldn’t contemplate our future beyond the next morning — we were too excited, too tired and too cold.”

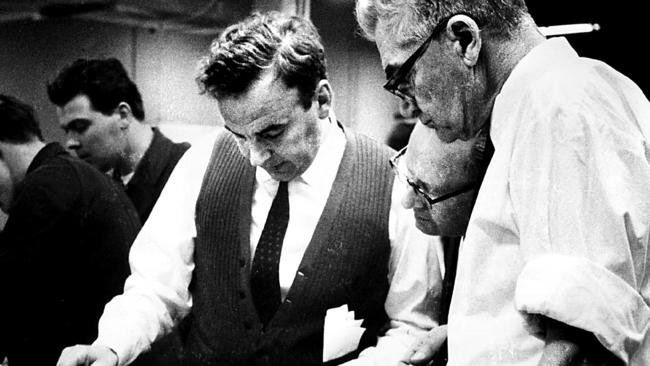

Somewhere inside the Mort Street building, an ABC television crew was chasing 33-year-old Rupert Murdoch, who was smiling enigmatically at the cameras.

Within hours Australia’s first truly national newspaper would hit the streets for the first time. It was a gamble that could make or break the young proprietor. But this was a gamble Murdoch was willing to take to realise his dream of creating a unique new voice in national affairs, a newspaper which would be independent, outward-looking and optimistic, and which was tailor-made for a changing Australia.

As the first edition rolled off the presses that evening, the exhausted staff knew they had achieved something special, but exactly what? Few could have imagined on that winter’s evening that their new newspaper would transform Australian journalism and exert a profound influence on the nation’s political, social and cultural landscape for the next half-century.

In the words of its inaugural editor Max Newton; “It was such a wild idea, a mistake, a dream of such compulsion.’

It was The Australian.

In the early 1960s the notion of a national newspaper seemed nuts at first glance. Australia was dominated in body and mind by the tyranny of distance. How could someone print and distribute a daily paper across such a vast land without modern technology, transport and a national distribution network? And were Australians ready for a truly national newspaper given the parochialism that infected their outlook on life up to and including their vastly different football codes? If the states couldn’t even agree on a standardised railway gauge, what hunger would there be for a newspaper carrying national news?

Murdoch wasn’t so sure. By 1962 the idea of a national paper was already fermenting in his mind; in early 1964 Murdoch moved to make his dream a reality. He quietly moved to Canberra, set up headquarters for his new venture in Mort Street, and set about trying to recruit the elite of Australian journalism.

Murdoch wanted his new paper to challenge the orthodoxies of federal politics at a time when Australia was entering its 16th year under prime minister Robert Menzies and he sought out unconventional people for that task.

“At that time Australia had been asleep for a very long time and I think Murdoch wanted The Australian to introduce an element of adventure,” says Walter Kommer, now 83, who became deputy editor for the new paper and later editor.

Murdoch had held secret discussions with Max Newton, an unpredictable and maverick word-smith and economist who had impressed Murdoch by taking on Menzies and the bureaucracy while working for The Financial Review.

Murdoch biographer William Shawcross describes Newton as “a troublesome, brilliant neurotic, burning comet”. It seemed, at least initially, as if Newton was born for the role as the contrarian editor of the new national daily.

In early 1964 Newton resigned from The Financial Review to become the first editor of the new newspaper, convincing colleagues such as Kommer to join him.

As word of the ambitious project spread, journalists lined up to join.

“It was to be the first new newspaper since who knows when and there was a feeling Australian journalism badly needed a shake-up,” recalled James Hall.

The new paper was to be called The Australian — an unusual name but one which would under-line its national role. It was suggested by Hank Bateson, the editorial manager of Mirror Newspapers, reviving a name first used by W.C. Wentworth for a newspaper he published in the 1820s.

But as Murdoch was quietly building up his resources for The Australian, disaster struck. In May 1964 Fairfax abruptly bought The Canberra Times, saying it would be developed as a national daily.

Newton believed this would kill The Australian before it began.

“In those terrible hours and days, when we realised our predicament, Rupert showed some of the steel, the gambler’s recklessness and the foresight that have since grown to such immense maturity on the world stage,” he later wrote.

Says biographer Shawcross: “Murdoch would not be defeated. He decided that the only thing he could do was to go for the big time and publish a national paper at once, instead of in two years or more.”

Murdoch set himself barely three months to bring to fruition a dream which in many ways was years ahead of its time.

“This was an enormous gamble,” Kommer recalls in a telephone interview from Perth. “I don’t think even Max (Newton) quite understood the enormity of the risk that Murdoch took at that time. It is all very well to see Murdoch in terms of (what he owns) today, but in those days he was just the new fellow on the block and I was very aware of the risk he was taking.”

Such was the rush that there was no time to examine other national newspapers in Britain or the US and use them as a template for The Australian.

In the lead-up to the paper’s launch, Murdoch faced challenges across the board, logistically, technically and financially.

For his paper to secure a viable long term future, he needed national advertising, but this was largely an alien concept in mid-1960s.

Murdoch thought the national paper should be based in the national capital but The Australian was initially pitched awkwardly as being both a true national newspaper and a local paper to those in Canberra, a city of less than 100,000 people at that time. Its dualistic motto was “to report the nation to Canberra and Canberra to the nation”.

“We were based in Canberra and in the beginning we were quite confused about where our market was but it quickly became clear it was not in Canberra but in the big cities,” recalls Kommer.

Murdoch knew his biggest challenge would be technology and logistics and even then he probably underestimated the task. In 1964 The Australian had to be produced in painstaking fashion. Matrices pressed from lead type and used as the basis for printing the pages were flown from Canberra to Sydney and Melbourne, where the printed paper would then be dispersed around the country by plane and trucks.

“I think Rupert was smart enough and well-informed enough to be aware that new technology would soon be on its way because flying matrices to Sydney and Melbourne was a pretty far-fetched idea,” says Ken Cowley, whom Murdoch had employed to oversee production.

Cowley says Murdoch’s optimism that such obstacles could be overcome was not shared by the News Limited board.

“The News Limited board came up to Canberra to have a look and they were terrified at the idea,” recalls Cowley. “They were very worried about how it would all work and how you could publish a paper in Canberra and send it all over Australia.”

Murdoch was determined that his new publication would target decision-makers, appealing to upwardly mobile white-collar, university-educated Australians in a way which no other publication had done.

In his book Murdoch’s Flagship Denis Cryle records how The Australian’s prospectus in 1964 anticipated appealing to “the widening horizons of today’s women” and employing “the most intelligent and the most able journalists available in the country”.

Says Cryle: “In retrospect, the establishment of The Australian marked an important post-war moment, not only socially and politically but professionally, by anticipating (in its prospectus) “the coming intellectual ferment in the big cities” and holding out the promise of a ‘new type of elite force among journalists.’ ”

Murdoch was setting his new paper up to be a player in the national debate rather than merely a record of that debate. In doing so, he knew it would give him greater influence in that debate.

“He certainly assumed that by having The Australian we would become a part of that discussion and we did,” says Kommer.

Says Cowley; “Rupert could see more than I could the political strength of having a national newspaper and it made him, once he had achieved it, virtually the most powerful man in Australia.”

In part, Murdoch’s determination to push ahead with his bold venture was in keeping with the nascent mood of the times, when Australians were beginning to question the status quo on many fronts.

As former editor David Armstrong put it: “The Australian was the beginning of the right idea at the right time ... more people started questioning Australia’s place in the world, a new interest stirred in issues of national identity and national affairs. The winds of counterculture would blow from American to a receptive young population here — The Australian sought to tap into the new moods rather than resist them.”

The Australian’s first cartoonist, Bruce Petty, has said he believes Murdoch spotted this mood. “He knew there was a kind of restlessness among young people. There was a political anachronism in federal parliament that (prime minister) Robert Menzies wasn’t enough any more, there was Asia and the Cold War,” said Petty “ I think he sensed the politics of the day very accurately.”

Murdoch wanted his newspaper to radiate an independent, optimistic and outward-looking view of a changing Australia. It was a youthful vision which in part reflected the youth of all the key players involved in giving birth to the paper. Murdoch was only 33, Newton was 34, Cowley 30 and most of the journalists were in their 20s or early 30s.

This young team also knew that their jobs and perhaps their careers depended on the success of the new paper. They worked around the clock between May and July 1964 as dummy run after dummy run was held to try to perfect the paper for launch on July 15.

“It was a very big, emotional time,” says Cowley. “My wife was telling my children at dinner last week “you forget that your father would be gone before breakfast and would not be home before 10 o’clock at night.”

On July 14, 1964, the eve of the first edition, the staff of The Australian were running on a cocktail of adrenalin, nerves and sheer excitement. “It was awesome, just awesome,” recalls Cowley, a wide grin spreading across his face at the memory.

Murdoch, Newton and Kommer decided the paper would lead its inaugural edition with a story on Liberal-Country Party tensions in Cabinet, a national yarn which sat neatly with its declared mission to spotlight national politics.

The main picture story on the front page was the rescue of skiers who had been missing for three days. Inside the paper there was a whole page devoted to gossip, while other stories in the paper included a walkout by audience members in Brisbane disgusted by the “blasphemy” of the play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf ?

The first editorial urged Australians to strive for maturity, self-control and sacrifice.

Curiosity sales for the inaugural edition topped 200,000 and many staff were proud of what they had achieved.

“That morning after the night before, we thought we had at least made a difference and it felt good,” recalled James Hall in a 1996 article in The Australian.

But deputy editor Kommer was disappointed with the final product. “We’d had dry runs which were better than the real one and I can remember that Max and I felt a sense of letdown. We didn’t think the first issue was much to write home about.”

But within weeks The Australian was already making an impact on other newspapers and on other journalists.

“It shook up journalism and the press gallery,” says Brian Johns, who was recruited from The Nation to be the paper’s first political correspondent and who would later become managing director of the ABC.

“The gallery had a cosy morning newspaper club and an afternoon paper club, their newsrooms were provincial and they exchanged news,” says Johns. “But The Australian broke those clubs because if you had a story in The Australian everyone knew about it. It was exciting and it stirred up not only the gallery but the whole media.”

The Australian also shook up reporting on federal politics by focusing on the bureacracy, which had not been done before. It divided coverage of politics into rounds to allow reporters to specialise in areas such as foreign affairs, health or education.

“When we set up departmental rounds the public service became nervous about what we would write about them,” says Johns.

Ranald Macdonald, the former managing editor of Melbourne’s The Age, once recalled : “The Australian brought change to The Age by example. It covered at a national level isses in greater depth; gave much greater emphasis to foreign news and provided much better economic reporting than The Age.”

Johns recalls Murdoch being “intensely interested in politics and Canberra” but says the proprietor was more interested in Johns trying to shake things up rather than taking a particular political line.

“It wasn’t about left or right or Liberal or Labor,’ says Johns. “Australia was waking up, Australia was asleep at that time.”

Johns says Murdoch told him early on that The Australian needed to have the best letters column in the country, from every corner of the land, to reflect its national role and to remind readers that it truly was a national newspaper.

The Australian also transformed the reporting of business and finance by interpreting business news rather than merely reporting it.

This was driven by its economist-editors, Newton and Kommer, and Kommer believes it was the greatest strength of the paper in its first years.

While Murdoch knew this was important, he was also wary of the two men turning The Australian into another version of The Financial Review. To offset this, Murdoch mimicked Fleet Street in devoting a page of the paper to gossip in order to showcase what the paper called “the world’s lighter side”. The column, written by Arnold Earnshaw, was initially called by the made-up name of Peter Brennan and later became the Martin Collins, after Martin Place in Sydney and Melbourne’s Collins Street.

“The gossip page was driven by Rupert, who was very concerned about both Max and I coming from an economics background and he feared the paper might become too academic and serious,” says Kommer.

Weeks after the paper was launched the historian Ken Inglis wrote a glowing review, describing it as a “clean and handsome thing” which was “fit to place alongside the best-designed newspapers of our language and time”.

The Australian poet Alex Hope was less inspired by the broadsheet format and complained that “your arms get tired because the paper is so wide, and it gets in the porridge because it is so long”.

Kommer says Murdoch was far from satisfied with some of The Australian’s early editions and that he would spend hours raking over the paper, discussing ways to improve it. “For him this was the big dream and he put everything into it.”

Ken Randall, who was recruited as defence and diplomatic correspondent, recalls him handing notes to the staff pointing out what needed to improve.

“He gave me a note once saying, “What you write is very interesting but it’s not bloody news”, Randall laughs during a telephone interview from the National Press Club, of which he became a long-time president.

Murdoch wrote a daily bulletin for staff outlining what was wrong and right with that day’s paper. A consistent theme was the need for The Australian to stand-out among its competitors.

“I’m afraid that today’s paper is a rather mixed bag,” he wrote in his critique of the paper’s edition of February 10, 1965. “As usual, we had a wonderfully wide cover of news and general reading in all departments of the paper, although there were no particular pieces of outstanding writing or exclusive news stories to give us the distinction which we must always strive for.”

He then raked over the major stories, saying that the front page splash should have been reported more factually and with less interpretation. “By all means let us have interpretive reporting but never until we have told the facts first.”

He lamented the fact that the “Darwin story on the marooned family came through so late, thereby resulting in a very bad comparison between ourselves and all other daily newspapers”.

In that day’s paper, as with almost every daily bulletin he wrote in the first half of 1965, he outlined spelling and typo errors, imploring the sub-editors to “try harder for perfection in this direction”.

On that day he queried aspects of the editor’s news judgement, such as the decision to place on Page 7 a story about the British government’s decision on TV advertising for cigarettes — “a most important story of interest to every single person in the community”.

About the business coverage, he wrote: “I am well aware that our finance pages are outstanding, but I have a sneaking feeling that we are overplaying the special articles on economic subjects at the expense of news about companies — in which, incidentally, most of our readers have shares.”

“Finally, is anyone hearing comment about the (comic strip) Wizard of Id? I strongly suspect we have fluked a real winner.”

Over the course of the next month, Murdoch’s bulletins contain common themes — enormous frustration at the continued spelling, grammatical and typo errors and the need for fresh, lively and powerful stories to lift his new paper above the pack.

One February 12, 1965, he writes: “Please note we are not a left-wing Labor paper nor are we tied to any particular political party or philosophy. We are simply in the business of reporting, interpreting and sometimes commenting on the facts – IN THAT ORDER.”

No detail was too small to escape his notice. On February 18 he wrote: “I notice the Russians in the UN yesterday were ‘smiling nastily’. Really!”

“The Vogue fashions and cooking look beautiful on p11, another distinctive and worthwhile feature.”

“The sport seems very good although careless in some headlines. We badly need more Melbourne racing.”

In his bulletin of February 23 Murdoch writes down 35 mistakes he gleaned “from just a quick read of the paper”. Four days later he writes that “the so-called ‘culture’ page seemed to me to be nothing more than a grouping of rather dull essays written by people amusing themselves with the use of long words”.

On April 28 he writes: “What an excellent paper we have today… if we can keep this up, improve it further in some obvious areas and add better pictures, there will be no holding us!”

Then on March 1 he writes: “A wonderful paper for a Monday. Perhaps it is just my elation at our first ever profitable issue!”

Almost immediately after launching the paper, the Canberra winter of 1964 dealt Murdoch a blow when heavy fog or poor weather too often prevented planes from taking off and delivering the matrices to Sydney and Melbourne.

Both Cowley and Kommer at various times accompanied him as he drove to the airport to implore pilots to bend the rules and take off into the fog to make sure his new paper wasn’t late getting to the streets. On the days when the planes didn’t take off the matrices would have to be driven to Sydney, delaying the national paper and in some cases ensuring it didn’t appear at all in outposts like Perth, Darwin and Cairns.

“He was saying to the pilots you’ve got to fly them,” recalls Cowley. “He was almost threatening them, saying if you don’t fly them we’ll have to get someone else to fly them.”

Recalls Kommer; “One day Rupert asked me to go to the Department of Civil Aviation and ask them if we could put (burning) oil drums along the runway to dispel the fog. The director of Civil Aviation looked at me and pointed to his head and said “Have you gone mad?”

After three months The Australian was selling 80,000 copies a day which was below the break-even figure identified before its launch. Murdoch knew it was the technical and logistical issues rather than the product itself that posed the great danger to the survival of his beloved paper.

He dispatched his people, including Cowley, to the US and Europe to study new developments which would allow the automatic transmission of pages, removing the need to fly the matrices to Sydney and Melbourne.

Murdoch’s hands-on involvement with the paper only grew in late 1964 and early 1965 as he willed it to survive, but Newton became frustrated by Murdoch’s approach. He disagreed with the proprietor on key issues such as the Vietnam War, protectionism and Catholic education and tried to exert his own stamp on the paper’s coverage.

“Max misread his relationship with Rupert,” says Kommer. “Max thought this was a joint venture in the full sense of the word between himself and Murdoch and he didn’t realise that in the end he was just an employee and no more.”

In early 1965 Murdoch replaced Newton with Kommer, a more steady and reliable character. The paper was still finding its voice but was ahead of its rivals on some issues, including its strong opposition to the war in Vietnam.

The paper’s circulation was still very weak, sometimes barely over 50,000 and this, combined with the ongoing distribution problems, saw Murdoch reportedly lose between $25,000 and $45,000 a week.

“I knew better than most what we were losing and I knew he was relying on the goodwill of the Commonwealth Bank to survive,” says Kommer. “But I never thought the paper would fold because I could sense Murdoch’s absolute iron will to make this happen and to make the newspaper work.”

Wrote Cryle: “The sobering sight of Murdoch walking through the Mort Street office waving hefty bills and declaring “I can’t keep doing this” suggests that for all his audacity, he was acutely aware of the stakes.”

By early 1967, he knew the paper had to be moved to Sydney, to reduce costs, improve distribution and to take better advantage of the advent of facsimile, which would greatly boost The Australian’s chances of survival.

On the weekend of March 16 and 17, 1967, The Australian literally trucked its way from Canberra to Sydney carrying composing equipment, facsimile machines desks, chairs, lockers — the lot.

“It was an extraordinary gamble but a conga line of 50 trucks and vans headed up the Hume Highway in the dead of night and into the breaking dawn,” administrative manager Don Davies said. “Everything was in place for Monday’s edition (in Sydney) — it remains one of the miracles of The Australian.”

The move to Sydney triggered the paper’s revival after its difficult birth. Within three months circulation had risen to 75,000.

In 1989 Newton wrote that “The Australian in 1964 was a good 20 years ahead of its time technically, editorially and financially. It was also ahead of its market, probably too far ahead.”

Cowley believes that while Murdoch created The Australian, the newspaper also played a key role in creating Murdoch.

“It exposed him to a lot of decisions and initiatives that lifted him,” says Cowley. “He was always brilliant but it just lifted him higher and higher and his life since has been an amazing journey.”

By 1970 sales had cracked the 100,000 mark. The paper had established itself as the most influential media voice in national affairs, a position it has never relinquished. Murdoch’s dream of creating a viable national newspaper in his own country had proved much harder than he or anyone else had imagined. But he had done it. The Australian was here to stay.