Inquest the last hope for dying doctor: I didn’t kill mum

Stephen Edward was charged with murdering his mother before a terminal cancer diagnosis forced prosecutors to drop the case.

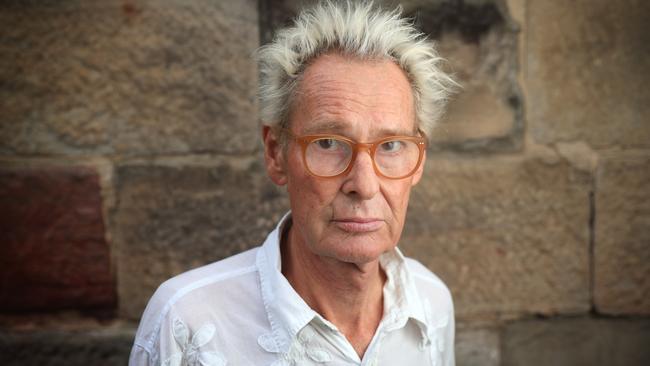

Having written a book to clear his name over the deaths of his elderly parents two days apart, terminally ill ex-GP Stephen Edwards hopes an inquest will finally uncover the truth.

Mr Edwards, 67, was set to stand trial for the murder of his mother, Nelda, in 2020 when prosecutors in Tasmania abandoned the case because he had been given only months to live from advanced liver cancer. But here he is still protesting his innocence, still adamant he didn’t kill 88-year-old Nelda or improperly hasten the death of his father, David, 91, in the early autumn of 2016.

“The inquest is a way for this to be resolved one way or another,” he told The Australian. “I would like to be absolved and I suppose the police would like some kind of finding that I was guilty of what they charged me with.

“We’ll see what happens.”

There’s just one catch: with the coronial hearing not due to commence in Hobart until October, Mr Edwards can’t be sure he will be around to give evidence, so precarious is his health.

Physically, he’s a shadow of the man he was after shedding more than 20kg. The cancer has spread remorselessly from the liver through his abdomen and now threatens to engulf his heart. “Basically, I’m a day-by-day proposition,” he said.

The inquest has the potential to be explosive, cutting across the blurred ethical and legal lines doctors confront when treating elderly people or the very ill in that last, often trying stage of life.

And unlike the aborted murder trial, the coroner will investigate how both his parents died – as well as the medical care Mr Edwards provided in their final days. Bracketing the cases was something he urged coroner Simon Cooper not to do, arguing it could put him at risk of further prosecution.

“I think it’s a way for the police to get their hands back on it, because they’ve made reference to the book that I wrote,” he said at his cramped rented flat in Kings Cross, central Sydney.

“They seem to feel that, you know, if I’m well enough to write a book, then I’m well enough to face another trial, and I think they’re hoping the inquest will open the door to that.”

His book, Evil Conjectures, set out the defence Mr Edwards didn’t get to make to the charges of murdering his mother and conspiring with his older brother, Robert, to cover up the alleged crime.

The proceedings were discontinued on March 26, 2020 when Tasmanian Director of Public Prosecutions Daryl Coates SC submitted it would have been “oppressive” given that Mr Edwards was so gravely ill and posed no risk of reoffending.

By then, he had spent three months in jail on remand and been stripped of his medical licence.

Nelda died on March 4, 2016, barely 48 hours after her husband of 68 years went to the grave. What Mr Edwards didn’t know until it was too late was that his parents had made a pact to die together: they had been starving themselves and refusing liquids for at least a week at home in the dress-circle Hobart suburb of Sandy Bay.

Mr Edwards admits he made mistakes. He was naive to think the proximity of the deaths wouldn’t arouse suspicion and, in hindsight, agrees it would have been wiser to have handed over to a local GP as soon as he realised the gravity of his father’s condition and, later, Nelda’s determination to die rather than live without him.

But he insists he did no more or less than he would have for other elderly patients in “existential distress” as death neared. “I did not murder Mum and I most certainly did not kill my father,” he has said. “That would be against everything I stand for. It didn’t happen.”

Prosecutors alleged, however, that he intended to either kill his mother in accordance with her expressed wish to end her life, or was reckless in administering drugs to her that had been prescribed for his father by another GP.

Mr Coates told The Australian last year the evidence against Mr Edwards was strong and there was a “reasonable prospect” he would have been convicted. “The Crown case against him was based on expert evidence, circumstantial evidence including post-offence conduct after his mother’s death and admissions made to police,” the DPP said. “Tasmania Police conducted a thorough and detailed investigation.”

A spokeswoman for the Tasmania coroner’s division could not advise whether Mr Edwards would be required to give evidence at the inquest. The former GP doubted he would be well enough to travel, but would be willing to appear by video link if the coroner agreed. Either way, Mr Edwards said he had nothing to lose “from the truth coming out”.

“There’s not much point in trying to put me back in prison because, you know, I’m just too sick,” he said. “I literally wouldn’t be able to pass muster … I’d be one day in a cell and then I’d be languishing in a prison hospital for the rest of the time, which isn’t a lot different from where I am now.”

Mr Edwards, who worked as a visiting GP to nursing homes on NSW’s central coast, conceded he gave both his parents “generous” doses of sedatives and painkillers. However, this was in line with the time-honoured doctrine of double effect relied on by doctors to push the boundaries to relieve the suffering of a dying person, essentially sanctioning the use of potentially lethal doses of drugs provided the intent was not to kill.

In the case of his father, who by Mr Edwards’ account was dying when he flew into Hobart on March 1, 2016, Mr Edwards obtained prescriptions for morphine and the sedative midazolam from David’s GP. He died next morning.

His mother’s situation was even more challenging. She and David had embarked on the hunger strike together after the sudden death in Thailand of their son, Glendon, 67, second of the four brothers. In their grief, the couple had decided they no longer wanted to live.

Refusing to be talked around, Nelda wanted to know why she hadn’t succumbed when she had fasted and denied herself water for the same time David did. Mr Edwards wrote that he explained, gently, that she was more “robust” than her chronically ill husband. (This did not mean his mother was healthy: her medical issues included atherosclerotic and hypertensive cardiovascular disease and vascular dementia). On the morning of her death, March 4, she had begged him to give her something to help her sleep.

“I just want to rest properly,” he quoted her as saying. “Mum, you know I can’t do that,” he replied. “Yes, you can,” she persisted. “You gave something to your father that let him sleep. Please, Stephen, just a few hours.”

Mr Edwards wrote that he reluctantly agreed to help her – to sleep, he emphasised. He gave her three doses of the sedative clonazepam, and morphine syrup before she dozed off.

By 4pm, her breathing had become ragged and he realised something adverse had happened – a heart attack, possibly stroke. Robert and another brother, Leigh, were at the house with other members of the family and there was a discussion about calling an ambulance. But Nelda would have hated the “indignity” of going to hospital at that point, they agreed.

Mr Edwards wrote: “When her groans started, I gave her a little of the morphine and midazolam by injection that I had used with my father when he was unconscious but agitated. My reaction as a doctor was automatic and compassionate. My mother’s grimacing and distress returned only once and I gave one further dose of the medications: standard medications used in nursing homes all around Australia at standard doses.

“My mother died peacefully an hour later.”