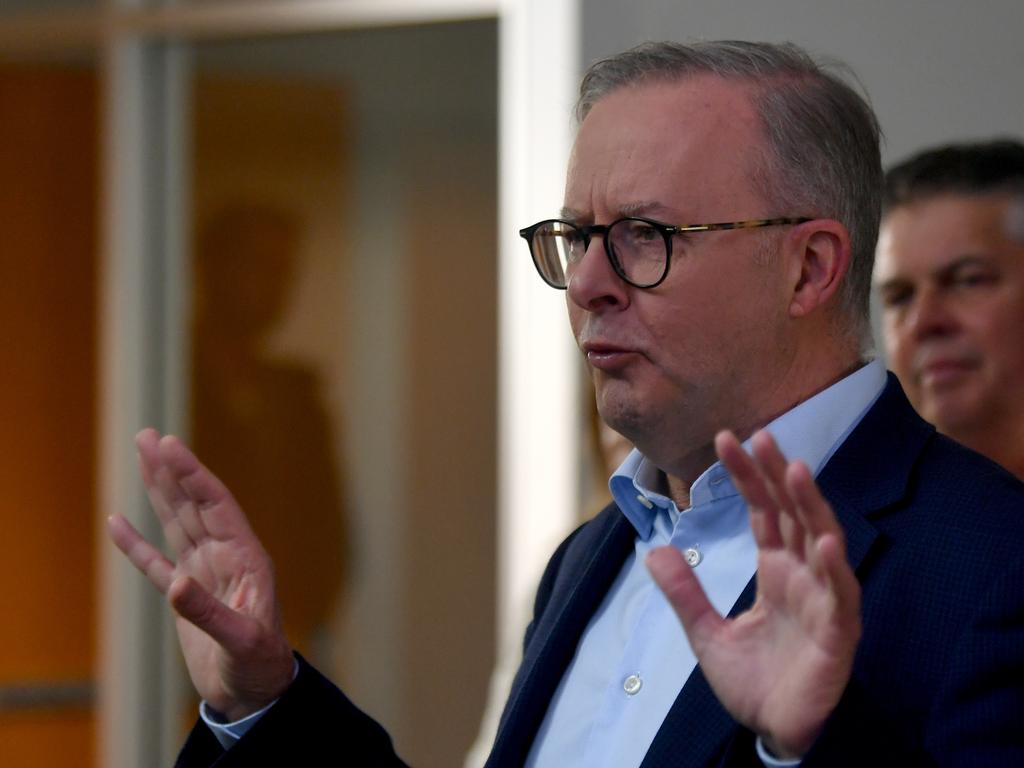

Anthony Albanese’s radio interview with 2GB’s Ben Fordham on Wednesday summed up the difficulties he is having explaining his government’s plan for the Indigenous voice.

The concept of the voice is not complex, and successive polls show Australians see it as fair. But things can fall apart fast on talkback radio. It does not help that Mr Albanese is unable to answer some of the questions Australians have.

For example, Mr Albanese would not say if his government intended to legislate the advisory body in the event that Australians say no to enshrining it in the constitution at a referendum this year.

Is a failed referendum the end of the voice in any form?

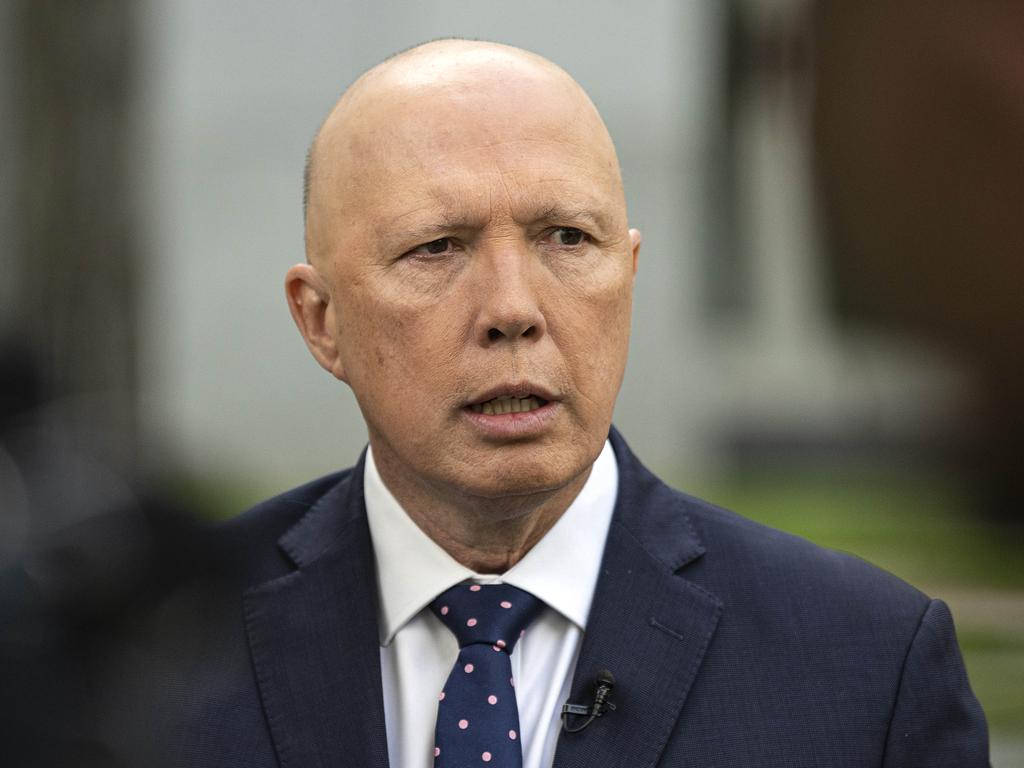

The Coalition had funded a considerable body of work towards a legislated version when it lost the election in May last year.

There are plenty of Uluru purists who will not contemplate a legislated voice as a fallback position, largely because they have spent more than five years since the release of the Uluru Statement from the Heart focused entirely on constitutional enshrinement.

Disciplined optimism is a strategy that has served them well. It has been a masterclass in perseverance and hope.

Indigenous leaders Marcia Langton and Tom Calma, both longtime supporters of a voice in the Constitution, oversaw the design of a model they were told would only ever be legislated.

Look where these Uluru supporters are now.

Inside the yes campaign is fear that, by even countenancing a voice that is legislated only, that is all Australia will get. Thinking goes something like this: the first time there is a problem with a voice member or the body itself – and that is entirely possible – a government could opt to abolish the body rather than fix it. If the voice was in the constitution, future parliaments would be obliged to reform it in response to scandals or flaws and to suit the circumstances of the day.

Marcus Stewart co-chairs the body that most closely resembles a legislated Indigenous voice in Australia – the First People’s Assembly of Victoria – and he captures the mood in the yes campaign when he says: “All our energy and effort will be spent on winning the hearts and minds of the Australian people … we can’t afford to get ahead of ourselves or distracted”.

The government sees multiple problems with providing draft legislation on the design of the voice before the referendum.

One is that people could think – and be encouraged to think – they are being asked to vote for that detail. In reality they will be voting only on the principle.

Legal experts see dangers in finalising or even proposing the voice design before a referendum because it could defacto “entrench” a model that needs to be flexible.

Another problem is probably best summarised by Mark Leibler, co-chair of the former Referendum Council, who says: “Once you start with the minutiae it will turn into a huge debate over individual provisions in the legislation which is not what the referendum is about.”

Some of Mr Albanese’s answers sound worse than the reality.

He acknowledged he had no legal advice on the voice from the solicitor general. In fact, he has a panel of constitutional experts advising on it.

So far there are eight principles for the voice. This includes that the voice will have no veto power, that it will not have a program delivery function as the defunct ATSIC did and that the members will appointed according to the wishes of their communities – that is, by election or some other means. It is Labor’s challenge in coming months to articulate these principles clearly and assure Australians that, if the time comes, they will get a say in the final model.

“That level of detail will all be the subject of legislation”