Monumental time in indigenous history

In March 2018 a striking statue of an Aboriginal figure with a spear thrower was raised to a standing position in Perth’s Yagan Square.

On a fine March day in 2018 a striking statue of an Aboriginal figure with his “gidji”, or spear, and “mirro”, or spear thrower, was raised to a standing position at the heart of Perth’s Yagan Square, which is named after a Noongar resistance leader killed by a white settler in 1833.

Aboriginal artist Tjyllyungoo, aka Lance Chadd, who designed the 9m-high iron statue of Wirin, a benevolent primal spirit, describes it as a personification of “the eternal sacred force of creative power that unites and connects all life of boodjah, or Earth, our mother”.

Amid a fierce debate about the propriety of statues from the colonial era that signify European conquest and, in many cases, indigenous tragedy, does Chadd’s Wirin monument suggest a way forward? The artist, for one, is convinced of the need for racial “equality” in the country’s suite of public memorials.

“I’d like to see an equality of cultural representation through public art including sculpture – an equality in the number of statues made from high-quality materials that ensure longevity,” he tells The Weekend Australian. “It’s about equal respect. Only in this way will we represent the authenticity and true history of the country – the truth.”

Jason Wing, a Sydney artist of Aboriginal and Chinese heritage, and creator of a controversial bust of James Cook in a bronze balaclava, also holds to the more-not-less theory of Aboriginal public art. Says Wing: “I understand the frustration of Aboriginal people and other minority groups wanting to tear down existing colonial memorials. My mission is not to tear down but to build up. I want to see a one-to-one ratio. It’s the only way it’s going to be genuine.”

Wing, whose Battlegrounds exhibition interpreting tribal shields is at Sydney’s Artereal Gallery, asks why there is a statue outside the Mitchell Library of Matthew Flinders’s cat, Trim, but none of Aboriginal leader Bungaree, so-called “King of Port Jackson”? Bungaree accompanied Flinders on his circumnavigation of Australia and was the most regularly depicted colonial figure by visiting portrait artists. “Statues are not immortal, and they can be updated,” he says. “Why don’t we have an image of Bungaree etched into the sandstone base of the Flinders memorial?”

Kent Watson, founder and head of Monument Australia, a body that documents and preserves Australian monuments, says “the most appropriate” way forward is to erect monuments, statues or plaques to explain the “indigenous perspective” at existing sites that are controversial.

Monument Australia documents a number of memorials to Aboriginal people. Most are plaques, but statues have been erected to resistance leader Yagan, activist Mum Shirl, musician Jimmy Little, guide and “man of peace” Mokare, Sir Doug and Lady Gladys Nicholls, nomad couple Warri and Yatungka, politician William Ferguson, Aboriginal rights activist William Cooper, rugby league great Arthur Beetson, tennis champ Evonne Goolagong Cawley, boxer Lionel Rose, sprinter Tom Dancey and early 19th-century clan leader William Barak.

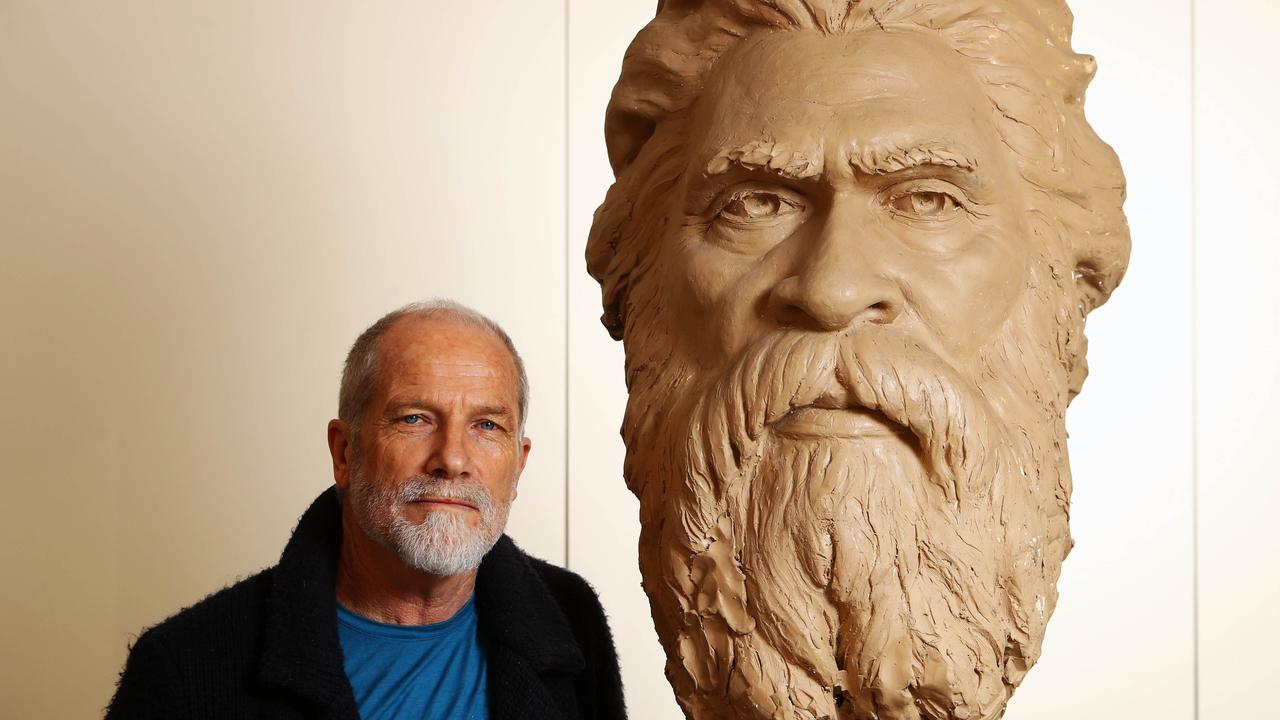

The latter has a pedestrian bridge named after him in Melbourne and is the subject of a monumental 4.2m-high sculpture by artist Peter Schipperheyn. The statue took two decades to make and, as told in The Weekend Australian Magazine today, languishes in the artist’s studio awaiting the estimated $1m for its completion.

Mariko Smith, a Yuin woman and First Nations assistant curator at the Australian Museum, points to at least one example where indigenous perspectives have been added to an existing colonial monument to establish a dialogue. A 1913 plaque on the Explorers’ Monument in Fremantle dedicates it to the memory of three pastoralists killed by “treacherous natives” in 1864. But in 1994 another plaque was added to explain the indigenous perspective.

The supplementary plaque takes issue with the existing monument by pointing out that it fails to mention “the right of Aboriginal people to defend their land”, “the history of provocation which led to the explorers’ deaths”, or the 20 Aborigines killed by whites in retaliation. In the process it commemorates “all other Aboriginal people who died during the invasion of their country”. Says Dr Smith: “The perception of a peaceful settlement, often communicated through existing statues, can be responded to by nearby memorials depicting indigenous resistance.

Pemulwuy is a popular nomination for a statue … in defiance and resistance to the likes of Cook and co.”

Nick Brodie, author of 1787, The Lost Chapters of Australia’s Beginnings and The Vandemonian War, believes some sites need urgent cultural attention. “Were it my decision … I’d plonk two large statues of the Aboriginal men who faced Cook’s landing party at Botany Bay right in front of his statue in Hyde Park, perpetually staring him down,” he said. Similarly, I’d lay a cast noose at Macquarie’s feet for as long as that particular statue remains in situ. Other options would be to create permanent spaces for temporary indigenous works, using contested sites to shift our collective cultural gaze from specific colonial moments into larger stories and threads of our shared history.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout