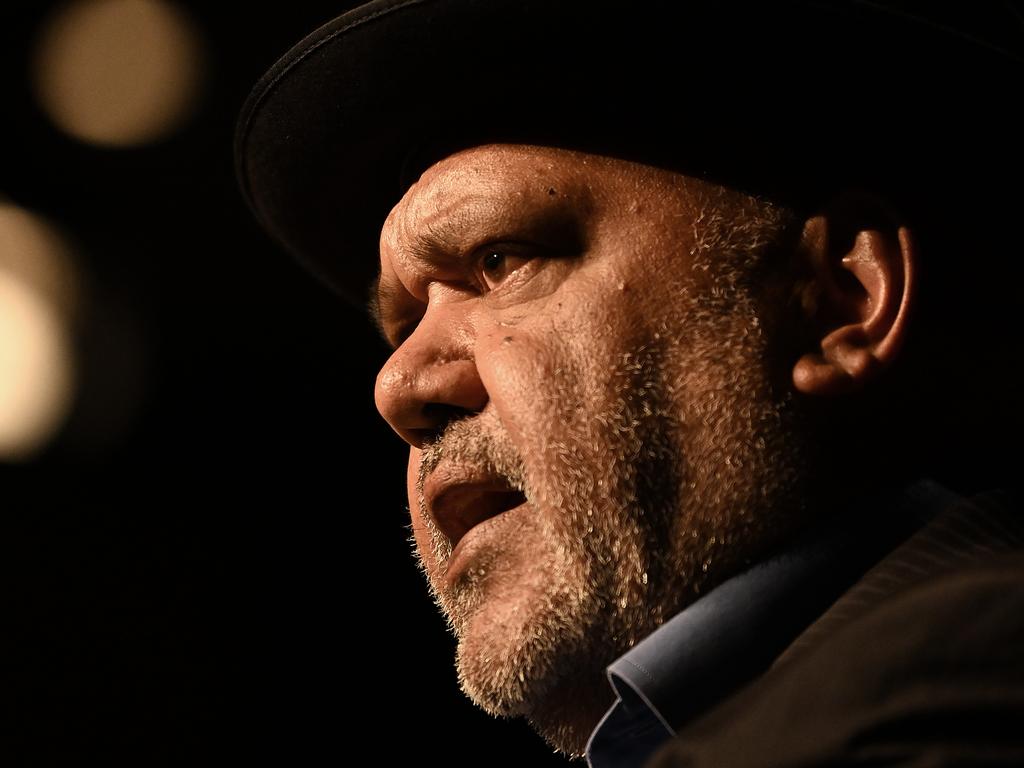

Marcia Langton: solar farms will have a bigger impact than mining on Indigenous

Massive solar farms will have a bigger impact than mining on Aboriginal lands, leaving Indigenous Australians even poorer, Marcia Langton says.

Indigenous leader Marcia Langton warns massive solar farms will have a bigger impact than mining on Aboriginal lands as she predicts the poorest Indigenous Australians – those living in remote communities – will become even poorer due to the tyranny of distance from services and government.

Professor Langton, who leads an Indigenous research team at the University of Melbourne, said the green economy could have worse consequences than land clearing because of the sheer scale of green energy projects.

Speaking at The Australian newspaper’s Outlook Conference in Melbourne on Wednesday, Prof Langton said there were opportunities for Aboriginal people in the green economy and already some Indigenous carbon trading networks, companies and foundations had been so successful “that pastoralists want to copy their efforts”.

“But the fantasy about the green industry – the green energy economy – that is happening right now is that it is entirely good and will save the planet from self-destruction when we hit 1.5C increase or even 2C – that is not the case,” she said.

“These projects may indeed have a worse impact than land clearing. The kind of land clearing you see in Queensland.”

Prof Langton made the remarks at a Closing the Gap panel discussion while responding to an audience member who wanted to know how the Indigenous estate would be affected by “the massive energy transition under way in Australia”.

“There is an upside and a downside,” she said.

“The downside is the massive solar farms that are being proposed and hydrogen projects will deeply impact Aboriginal lands. Some of them are enormous ... on present plans if they’re built you will be able to see them from space.

“So this is a big challenge for Indigenous communities who are landowners or have rights and interest in land. The footprint of the green economy will be so much greater than anything that anybody has seen before. Bigger than mines, bigger than tourism, bigger than urban expansion.”

The comments came after the Albanese government’s first budget last week spent more on initiatives to support Indigenous Australians to “respond to climate change in their communities” than on preparations for a referendum on a Voice to Parliament.

The $1.2bn in Closing the Gap measures in the budget included $105.2m “to support First Nations people to respond to climate change in their communities”, establishing “a new Torres Strait Climate Change Centre of Excellence” and a “Climate Warriors training program”.

Prof Langton said many Aboriginal people would not have a choice about whether they wanted to be part of the change.

“They will have these projects forced on them,” she said.

“But where they have the opportunity to freely be involved, there is the great advantage of being involved in an economy and being able to stay on their own country. So there will be economic development in the regions in a way that we haven‘t seen before. In many ways more acceptable than say agriculture or grazing.”

However, she stressed: “The footprint of the projects will be an enormous problem to face.

“The environmental impacts will be enormous,” she said.

“Imagine a solar farm that covers 17,000sq km, that’s what they’re envisaging. Imagine a windmill project that covers 20,000sq km, they are literally envisaging projects of that size with the towers 2km apart so in that entire area there is no place where there is no noise because of the noise of these machines.”

Prof Langton said she believed the subject required urgent research and demonstrated the need for an Indigenous Voice that would give Aboriginal people in remote locations a say.

She said the local and regional arms of the Voice were fundamental to the proposal that she oversaw with Indigenous leader Tom Calma and 50 other Australians in 2020 and 2021.

“The entire exercise was devoted to ensuring that people who don’t get to be heard in the debate have a formal voice for communicating their issues,” she said.

“The problem with the Indigenous affairs debate is that it is conducted by people who are by and large remote from the most severe problems that we seek to solve. We designed the Voice from the ground up by recognising that at its heart it must have local and regional voices ... the people who live in those areas must say what those local Voice arrangements look like, how they work, who is on them, how they want to choose their members.”

Prof predicted that about a third of the population of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people would not close the gap in health and life expectancy within our lifetime.

“There are populations of Indigenous people out there who will never close the gap and they are – I believe – the poorest people in Australia,” she said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout