Many steps to justice: diversion to keep indigenous people free

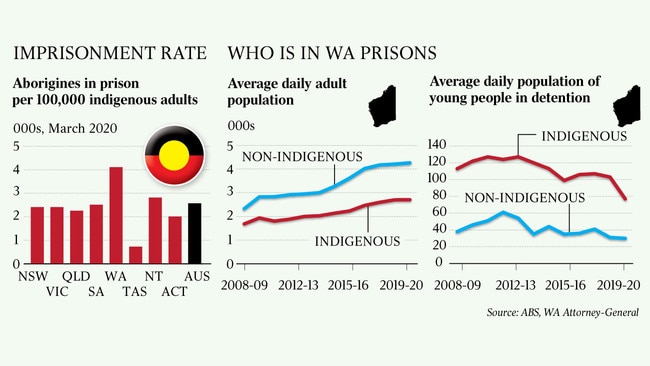

Alarming indigenous incarceration rates have begun to flatten among adults and decline among children in Western Australia.

Alarming indigenous incarceration rates have begun to flatten among adults and decline among children in Western Australia, under reforms that include night patrols to collect roaming kids in remote towns before they fall into crime.

The climb in numbers of incarcerated indigenous adults in WA has slowed since the introduction of a custody notification service that effectively gives every Aboriginal person a legal advocate on arrest. The WA government has also begun sending lawyers into the state’s jails to find prisoners who would be on bail if they had been represented in court.

Of all states and territories in Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adult imprisonment rates are highest in WA, where more than 4 per cent of the indigenous adult population is in jail, according to Australian Bureau of Statistics data for the March quarter. Nationally, 0.2 per cent of all Australian adults — indigenous and non-indigenous — were in jail at that time.

As WA jails heave with the sheer volume of prisoners and recurrent spending on its jails nears $1bn, the McGowan Labor government has committed to major changes to a justice system that incarcerated thousands of indigenous fine defaulters.

Many indigenous children from the remote Kimberley went to prison on remand in Perth because there was no responsible adult to look after them, so the McGowan government opened a “bail house” in Kununurra where charged juveniles stay with a youth worker who acts as a role model and carer.

And in partnership with indigenous leaders, the McGowan government has employed indigenous youth workers who recently began night patrols to intercept indigenous children on the streets. They take the children home or to a relative and visit families to talk to parents or carers. In the town of Halls Creek, the program coincided with a dramatic fall in youth crime within weeks.

Last month there were 44 offences in the town, compared with 138 in April.

WA Attorney-General John Quigley said: “We do understand that there is a pathway out of this mess and we are determined to engage with the local communities, who can help lead us out.”

Mr Quigley said his reforms were inspired by a 2015 speech by then WA chief justice Wayne Martin in which he said Aboriginal people were more likely to be questioned by police than non-Aboriginal people and, when questioned, they were much more likely to be arrested, rather than proceeded against by way of summons.

If they were arrested, they were more likely than non-Aboriginal people to be remanded in custody than given bail and Aboriginal people were more likely to plead guilty than go to trial. If they did go to trial, he said, they were more likely to be convicted. After conviction, they were more likely to be imprisoned for like offences and less likely to get parole than non-Aboriginal people.

Mr Quigley’s next step is to scrap fines-enforcement laws that captured the 22-year-old indigenous domestic violence victim known as Miss Dhu, who died in agony in a remote watchhouse while serving out a $1000 fine.

New legislation that will make imprisonment a last resort for fine defaulters and instead compel them to serve out their debts at community and government organisations has reached the state upper house. When it is passed, outstanding warrants of commitment for 238 people who have not paid their fines will be cancelled.

“We’re not gonna employ thousands of public servants to supervise (community service for fine defaulters), but we will have registered organisations throughout the state and anyone can apply, like sporting organisations, shire councils,” Mr Quigley said.

He said those who did not accept humanitarian arguments on the benefits of justice reinvestment projects that steered indigenous people away from jail should be persuaded by economics. “When an indigenous person goes to prison and is subsequently released, 80 per cent of them will re-enter the system.

“You’ve got to ask: where is the better investment? Is it to be made in keeping them out of prison and away from crime or is it better to keep on spending at the rate we’re spending?”

The cost of keeping a child in detention in WA is $484,000 a year or $1326 a day, according to a state Justice Department spokeswoman on Friday. Former chief justice Mr Martin said more than once in his calls for reform that it would be cheaper to send those children to Geelong Grammar then to a Swiss finishing school.

The number of children in WA’s juvenile detention centre has fallen to an average of 77 a day compared with 108 a day last year.

Read related topics:Indigenous Recognition