John Strehlow accuses Walter Baldwin Spencer of forgery

Author John Strehlow believes the famous anthropologist and observer of Arrernte people may have forged a crucial document to silence his critics

Author and director John Strehlow, the son of famous anthropologist Ted Strehlow, was lying awake one night when his mind turned to a century-old letter written, so it was always claimed, by a Lutheran missionary.

It was 2012 and Strehlow was deep in a 25-year project researching the lives of his grandparents, Carl Strehlow and Frieda Keysser, missionaries during the late 1800s and early 1900s at Hermannsburg near Alice Springs.

Their work had brought them into contact with Walter Baldwin Spencer, a University of Melbourne professor, doyen of Australian anthropology and 20th-century academic giant.

Spencer also was a racist and an architect of Stolen Generations policies whom Strehlow blames for preventing a First Nations treaty. Spencer saw “full-blood” Aboriginal people as “doomed”, writing in 1926 that “all that can be done is to treat those who remain as generously as possible”. He also urged the removal of “half-caste” children. Spencer’s evocative prose, personal charisma and popular books on early post-contact Aboriginal groups

influenced generations of scholars and, in Strehlow’s view, cast a pall over race relations for years. Even though Spencer’s contemporaries revered him as a man “as immune to error as is humanly possible to be”, Strehlow’s extensive research had already raised doubts.

Awake that night, and mentally poring over fragments of history gathered from archives in several countries across many years, Strehlow realised that if the pieces were to match, Spencer would emerge as a liar and a scientific fraud. In fact the 100-year-old letter — a document Spencer used to bolster his own findings and undermine his critics — must have been fake, Strehlow has now concluded. “Spencer was an unprincipled opportunist,” Strehlow tells The Australian. “He was certainly not just economical with the truth — he improved on it.”

Belief in God

When The Australian caught up with Strehlow, he was camping on the outskirts of Darwin in the blistering tropical heat.

A successful stage director, he is not an obvious candidate to tour the country in an old Ford, shopping the fruits of a quarter-century of self-funded research.

But Strehlow, whose father wrote books such as Songs of Central Australia and Journey to Horseshoe Bend, speaks as someone immersed in his subject, perhaps more so than many of the experts who still regard Spencer as an essential authority on the Arrernte and other groups.

“Spencer hijacked Australian anthropology,” Strehlow says. “He shackled it to the idea of Aborigines as primitive people who were going to die out, so we didn’t need a treaty or a settlement because they wouldn’t be around.”

To understand this point, you have to set your mind back more than 100 years to when the study of human societies was undertaken by missionaries and folklorists who saw myth and legend through a religious lens and Darwinists who viewed everything in terms of evolution.

Darwinism had opened new avenues to rational exploration but also engendered conflict with those who kept their faith.

“By persisting in their wrongheaded attempt to help these doomed peoples, missionaries were demonstrating not just their ignorance of indisputable, scientifically proven fact but their incorrigibility, for was it not the churchmen who had opposed Darwin all along?” Strehlow writes in his two-volume The Tale of Frieda Keysser.

The book portrays turn-of-the-century scientific thought as arranging peoples along a spectrum from primitive to evolved, based partly on their system of beliefs. Charles Darwin once wrote, “There is no evidence that man was aboriginally empowered with the ennobling belief in the existence of an omnipotent god.”

Scottish anthropologist James Frazer extended this idea by arguing societies evolved from believing merely in magic to developing organised religion and, finally, science.

Thus, whether Aboriginal groups believed in a godlike figure became hugely important: it helped decide if they were “savages” and “heathens” destined for extinction or capable of being saved.

Spencer, celebrated

Spencer graduated from Oxford in 1884 with a bachelor of arts in biology and three years later, aged 27, was appointed chair of biology at Melbourne University.

The intellectual life of Australia then resided mainly in Europe, and academics in the colonies needed to be bold or fail. Strehlow says Spencer largely drifted until the Horn Scientific Expedition gave him his big break in 1894 by introducing him to Francis Gillen, the stationmaster of the Overland Telegraph in Alice Springs. Gillen organised for Spencer to return in 1896 and watch a display of Aboriginal rituals.

The resulting richly illustrated Native Tribes of Central Australia, published in 1899 and with Frazer’s help, cast the pair as privy to the secrets of Arrernte culture. The book established Spencer as a celebrated scientist while Gillen, who Strehlow believes did most of the work, died largely unrecognised. Spencer thought Aboriginal people did not believe in God, except where missionaries had polluted their minds.

In 1901 he told Frazer: “We cannot find a trace of any belief right through the Central Tribes from Port Augusta to the Gulf in the north of … a being who could be called a deity.”

This was, in Strehlow’s view, part of the reason Spencer deemed Aboriginal people hopelessly primitive; it also allowed Frazer to feel he had “proved that Australian Aborigines could not have evolved” to the point of developing religion.

So it was very inconvenient for Spencer and his patron, Frazer, when Andrew Lang, a folklorist known for incisive criticism, obtained letters from Carl Strehlow contradicting Spencer’s findings published in the acclaimed Native Tribes. By then Carl Strehlow had established himself at Hermannsburg and had begun studying the Arrernte.

But, unlike Spencer, he lived alongside the tribesfolk, developed relationships with them and learned their languages before starting work on his books.

Although it was his father’s profession, John Strehlow writes scathingly of early anthropological practices.

“Anthropologists were men who lived in cities and lectured at universities, far from any of the tribal peoples they purported to know so much about,” he writes.

“They simply took a shortcut, communicating with the peoples they were studying in some half-language like pidgin English and convincing themselves that with a few hundred words … they could find out everything.

“Had they tried this with a European language … they would have been laughed out of court as ignoramuses, and their books dismissed as rubbish. How fortunate they were dealing with primitive peoples!”

Strehlow vs Spencer

Carl Strehlow thought the Arrernte believed in a benevolent sky-god called Altjira and that Spencer and Gillen had missed this through subtleties of language. He saw Aboriginal culture as in decline, in a “state of decadence”, but did not view Aboriginal people as especially primitive. Problematically for Spencer, Carl Strehlow had ready access to senior Arrernte leaders who could inform his correspondence.

John Strehlow says Spencer never engaged Carl Strehlow directly, thinking it beneath his dignity. Instead, in the pages of The Tale of Frieda Keysser, John Strehlow details the many half-truths and fictions he says Spencer deployed in private letters and minor public exchanges to erode Carl Strehlow’s credibility.

“He (Spencer) could not afford to lose Frazer’s backing — and Frazer was under sustained attack not just from Lang, but from … other social scientists in Europe. Spencer was succumbing to the temptation to force facts to fit a theory. When conflict arose, he simply suppressed the truth … he could not now admit he was wrong.”

Strehlow says he believes Spencer snookered himself by claiming credit for Gillen’s research, leaving him obliged to defend work he did not fully understand.

Near the end of The Tale of Frieda Keysser, Strehlow presents a list of what he says were Spencer’s 15 most egregious “falsifications”.

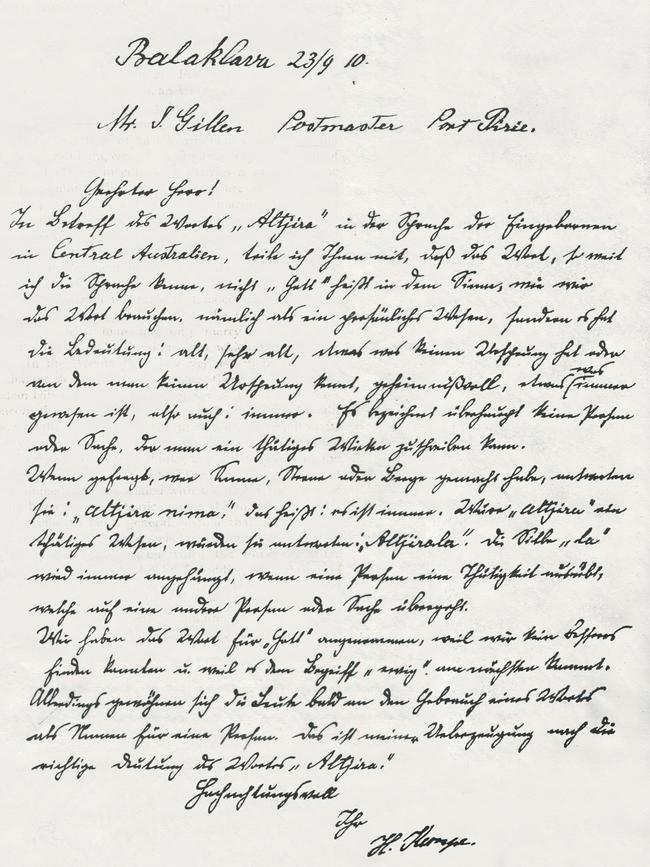

Chief among these is a letter Spencer produced soon after Carl Strehlow’s death in 1922, which is dated in 1910 and attributed to Hermann Kempe, one of Carl Strehlow’s predecessors at Hermannsburg mission. In the letter, Kempe unequivocally states that it was the missionaries (not the Arrernte people) who chose the word Altjira to represent God. The Kempe testimony contradicts Carl Strehlow’s evidence and suggests the Lutheran missionaries wrongly cited as tribal custom beliefs they had actually implanted themselves.

“The letter was crucial because it showed Carl didn’t know how to distinguish between people who were reliable informants and mission supporters,” Strehlow tells The Australian.

History consequently demoted Carl Strehlow’s work, and scholars dubbed his informants “Christianised natives” whose beliefs must have been hybridised. That view persisted largely unchallenged until Strehlow came along.

‘Dynamite revelations’

Strehlow found his first clue as to a potential scandal in German archives. Kempe had produced a paper in an obscure journal in 1881, just after Hermannsburg was established, too soon for Christianity to have had much influence. The paper describes native Arrernte religion featuring a godlike being called Altjira — this contradicted Spencer’s crucial letter, supposedly written by Kempe in 1910.

“If one looks at the life and activities of the Aborigines from the outside like this, one might almost think there was no trace of religion at all to be found among them … but this is in no way the case,” Kempe wrote. “There is no truth in the assertion that there are peoples devoid of religion, as many still assert, for even in a people sunk as low as this, there are still intimations that there are higher, spiritual beings, on whom they are dependent … there is also a good being. They call this ‘Altjira’ and attribute to him the creation of the sky and the earth.”

Intrigued, Strehlow checked Spencer’s correspondence from around the time of his dispute with Carl Strehlow. He found no mention of the vital document — the Kempe letter dated 1910 — that could have proved Spencer right just when it mattered the most, instead waiting until Carl Strehlow’s death to produce this critical evidence.

Next, Strehlow noticed that most scholars who accepted Spencer’s view relied on a typed translation of Kempe’s letter, which was actually produced in archaic, handwritten German script. Strehlow, a fluent German speaker, obtained samples of Kempe’s handwriting and checked them against Spencer’s document — a poor match.

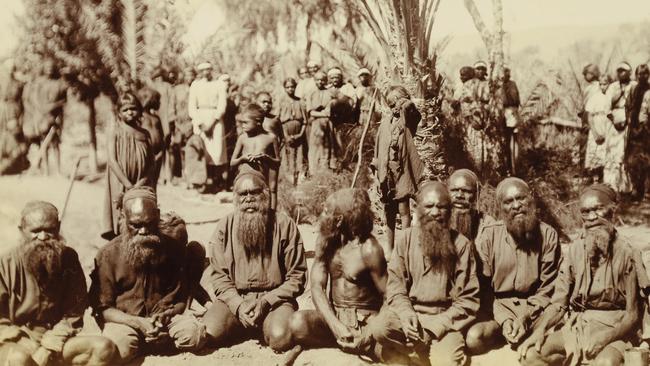

Finally, he stumbled on photographs of Carl Strehlow’s informants, the “Christianised natives” supposed to have misled him. The images showed the men looking distinctly traditional, nothing like mission converts.

“Everything hangs on the letter,” Strehlow says now.

“If the letter is a fake then not only is Spencer a forger but also his entire argument about Aboriginal people being a primitive group destined to die out has to collapse … it’s dynamite as a revelation, that’s why I was so cautious about it. If Spencer forged letters, then what about him can you believe?”

It’s a long shot to expect that the conclusions of an autodidact without institutional backing will immediately overturn decades of orthodoxy about a foundational figure in Australian anthropology.

The debate is also somewhat esoteric, given Spencer’s beliefs about Aboriginal people being destined for extinction were obviously wrong.

But Strehlow hopes his work will cause some searching reflection in a field responsible for ideas that caused Aboriginal people to “not be taken seriously” for years. He also hopes future studies will be kinder to his grandparents and to other missionaries.

“I would like people to understand the way information can become dogma, a belief system and actually an impediment to learning,” he says.

“Indoctrination is the great enemy of learning — it can strangle your brain and lead you to the opposite of the right conclusion.”

Strehlow pauses for a moment and then adds: “It’s just so obvious, when you look closely, that Spencer falsified facts.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout