Indigenous jail rates threat to Closing the Gap targets

Steep increases in the numbers of Indigenous adults jailed across the NT, Queensland and Western Australia threaten to derail the refreshed Closing the Gap agreement signed in 2020.

Steep increases in the numbers of Indigenous adults jailed across the Northern Territory, Queensland and Western Australia threaten to derail the refreshed Closing the Gap agreement signed with high hopes for a new way forward in 2020.

Fresh data from the Productivity Commission shows the decade-long agreement is in trouble at the halfway point.

Five of the agreement’s 17 targets were on track to be met when the data was last updated in November. Now only four targets are on track because the percentage of Indigenous babies born a healthy weight did not improve fast enough last year to reach the target of 91 per cent by 2031.

Data from men’s and women’s prisons across the nation are by far the bleakest indicators published on Wednesday night.

These figures from 2024 are deeply concerning to the alliance of Indigenous organisations working with governments to meet targets because of the known knock-on effects of crime and jail on families and children.

Only Victoria recorded a reduction in its adult Indigenous incarceration rate last year. The highest rate was in WA, where the Productivity Commission records that 6.73 per cent of all Indigenous men were in jail in on June 30. The next highest rate was in the NT, where 6.26 per cent of Indigenous men were in jail. The highest incarceration rate for Indigenous women was in WA, at 1.02 per cent. That is double the next-highest rate in Queensland.

The national Indigenous incarceration rate for Indigenous men and women has jumped every year of the Closing the Gap agreement except 2022. The rate at which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people go to jail in Australia has climbed 30 per cent since 2019.

When former prime minister Scott Morrison signed a refreshed and rewritten Closing the Gap agreement with Indigenous groups five years ago, every premier and chief minister committed to reduce the Indigenous incarceration rate nationally by 15 per cent by 2031. Instead, the rate at which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults are jailed in Australia has climbed 30 per cent since 2019, the baseline year for measuring progress.

The Closing the Gap agreement’s ambitions are underpinned by a new way of governing that not everyone has embraced.

State and territory governments agreed that making decisions with grassroots Indigenous organisations was the way to get results and cut waste, because community groups know better than anyone which services and programs have worked in the past and which ones are duplicated or unnecessary.

However, the Productivity Commission blasted state governments and the NT in a report in February 2024 that claimed bureaucrats were paying lip service to this promise. The report argued things would not improve while it was “business as usual” for state and territory governments.

On Wednesday, commissioner Selwyn Button returned to the criticisms of a year ago.

“We found that governments had not taken enough meaningful action to meet their commitments under the agreement,” he said. “The continued worsening of outcomes we’ve seen in some Closing the Gap target areas shows the importance of governments taking their commitments to the national agreement seriously, and taking meaningful actions to fully implement the priority reforms.”

Closing the Gap – which also failed more than it succeeded in its first incarnation from 2008 to 2018 – has had bipartisan support.

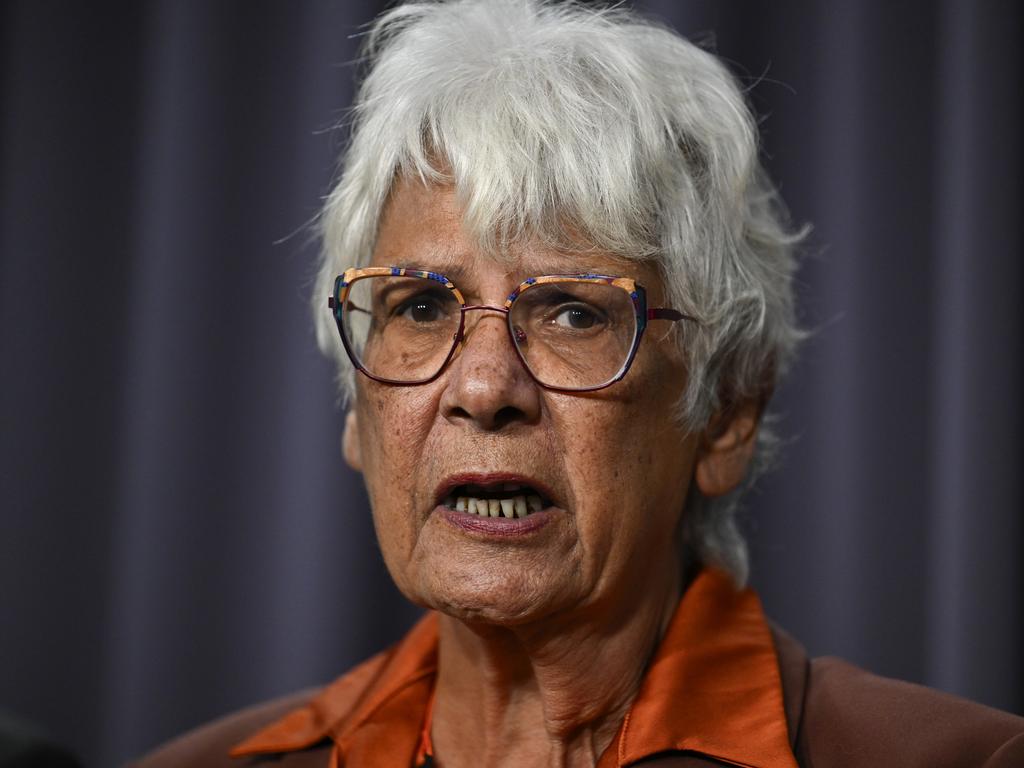

Indigenous Australians Minister Malarndirri McCarthy told The Australian it remained one of her top priorities.

“The National Agreement on Closing the Gap (signed by all Australian governments in 2020) remains the critical framework for delivering improved outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, in partnership with states and territories, local government and First Nations peak organisations,” she said.

“The Albanese government is focused on improving the lives of First Nations people through economic empowerment and jobs, easing cost of living and food security pressures in remote communities, and improving living conditions and wellbeing.

“There is no doubting Labor’s commitment to improving the lives of First Nations people and there is no doubting Labor’s commitment to Closing the Gap.”

While the latest update shows only four of the 17 targets are on track to be met by 2031, the states and territories are still making improvements in many areas.

Progress is recorded even if it is not swift or likely to meet the goal set down for 2031.

Every state and the Australian Capital Territory had made improvements – however slow – against a majority of the 17 targets in 2024. The NT, however, did not.

In the NT, figures recorded in August 2024, the same month the Finocchiaro government was elected, show a range of alarming results – for life expectancy for Indigenous women, the percentage of Indigenous babies born healthy, the percentage of Indigenous children enrolled in early childhood education, the percentage of Indigenous children who were developmentally ready for school, the percentage of youth engaged in study or work, and the percentage of adults employed.

The NT’s Indigenous incarceration rates for adults and youth increased in 2024.

Any effects of the CLP government’s measures in Indigenous affairs are not recorded in the latest Closing the Gap data. The update published late on Wednesday shows data from mid 2024.

NT Indigenous Affairs Minister Steve Edgington said the Finocchiaro government remained committed to the Closing the Gap agreement and the principles that underpin it.

“We are working in partnership with Aboriginal people to empower communities that want a greater say,” he said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout