‘In the name of Mabo, put royalties to work’: new Mabo Centre’s reform push

Billions in resource royalties could be unlocked from native title charitable trusts and used for Indigenous economic development projects as part of reforms driven by the newly created Mabo Centre.

Billions in resource royalties could be unlocked from native title charitable trusts and used for Indigenous economic development projects across Australia’s north as part of ambitious reforms driven by the newly created Mabo Centre.

Industry and traditional owner groups see the Mabo Centre as the right alliance to push for legal and policy changes to address “desperate economic and social need of remote and rural Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities that is recognised across the political spectrum”. Iron ore giant Rio Tinto Rio Tinto supports the centre as a founding partner.

The centre will launch in Perth on Tuesday with the aim of finding ways around obstacles that prevent native title holders from creating wealth from their land and sea rights.

One priority is long-wanted changes to tax rules and other laws governing charitable trusts that hold royalties from massive mining and resource projects on behalf of traditional owners. How those trusts can be used is tightly constrained. The Mabo Centre will lobby for the creation of a vehicle that has charitable standing but is committed to undertake economic development activity. In return, the new body would be subject to much greater scrutiny than existing Aboriginal organisations under the umbrella of the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations.

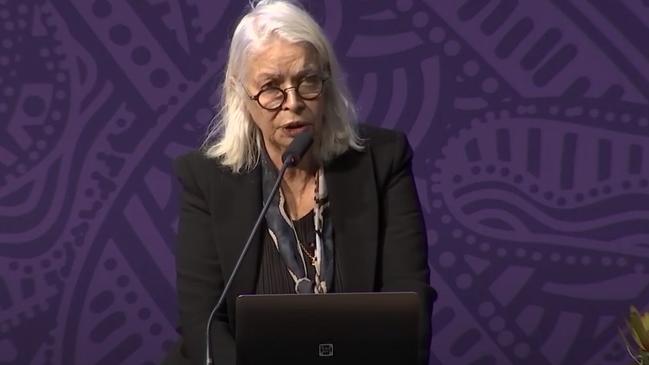

Mabo Centre co-chairs Marcia Langton, the esteemed Indigenous researcher and University of Melbourne associate provost, National Native Title Council chief executive Jamie Lowe, and Paul Kofman, dean of economics and finance at the University of Melbourne, will launch the Mabo Centre with artist Gail Mabo. Ms Mabo’s father, Eddie Koiki Mabo, was a gardener at James Cook University when he led the High Court case that resulted in the nation’s native title laws.

Professor Langton and Mr Lowe write in an essay in The Australian on Tuesday that some reforms are now overdue.

“After 32 years of native title, it’s time to bring about effective change in the administration of native title. Doing so will create an environment that improves the economic potential and status of traditional owners,” Professor Langton and Mr Lowe write.

“It is irrefutable that native title negotiations have led to the delivery of thousands of projects on native title land over several decades now. Despite this success, government and industry leaders remain ambivalent about the role and status of traditional owners and their organisations.

“This ambivalence is part of the cause of the desperate economic and social need of remote and rural Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities that is recognised across the political spectrum. Gaps in life expectancy, wellbeing and economic status can be effectively addressed by some long-overdue reforms.”

Ms Mabo sees Western Australia as the right place to launch the Mabo Centre, given native title rights apply so broadly in the mining state. However, the Mabo Centre’s research and work would benefit traditional owners across Australia.

“Through winning the case, Dad gave the right for all First Australians to celebrate those things we hold most dear to us,” Ms Mabo said. “To bring back our voices. To bring back our culture. To bring back strength to the proud people that we are.”

Ms Mabo told The Australian on Monday that she was now older than her father was when he died in 1992 aged 55. As she approaches her 60th birthday, she sometimes thinks about what his contribution might have been had he lived longer.

“I feel like I am just hitting my stride now. I know he would have done more,” she said.

It is one reason why she was happy for the Mabo Centre to take her father’s name and continue the work he started. She is a founding member of its advisory board.

The Mabo Centre’s third co-chair is Professor Kofman, a consultant for the European Options Exchange, the New York Board of Trade, Dutch investment banks and the Australian Office of Financial Markets. Professor Kofman is the Sidney Myer Chair of Commerce at the University of Melbourne. Supporters say the Mabo Centre brings intellectual heft and a much-needed co-ordinated approach to the reforms long understood to be necessary.

For example, industry groups such as the Minerals Council of Australia and traditional owners represented by the National Native Title Council agree that one way to unlock royalties money from native title trusts is to create a new category of corporation called an Indigenous Community Development Corporation. It would have charitable status but could take on commercial projects with the aim of lifting its Aboriginal members out of poverty and creating generational wealth.

The push for this reform comes as the Albanese government makes jobs and economic development the centre of its Indigenous affairs policy. There is bipartisan support for at least one of the economic measures unveiled by Indigenous Australians Minister Malarndirri McCarthy since she became minister last July – the expansion of the commonwealth’s Indigenous procurement policy. That policy, created by the Coalition, has awarded $10bn in government contracts to Indigenous businesses since 2015.

Professor Langton and Mr Lowe write in The Australian that the nation is at a crossroads “where the needs of Aboriginal traditional owners and the economy meet”. “Charting a way forward that encompasses respect for Aboriginal traditional owner rights and the need to develop the economy is the key task being addressed by the new Mabo Centre,” they write.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout