Hang on, they want to ban a world-famous climb in the Grampians?

An indigenous heritage crackdown threatens to devastate rock climbing in the sport’s heartland.

An indigenous heritage crackdown threatens to devastate rock climbing in the sport’s heartland.

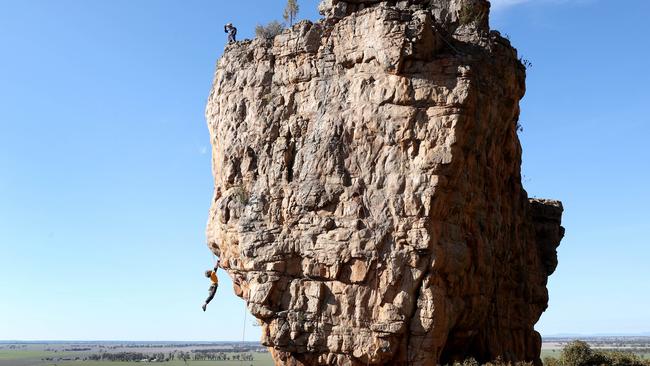

For decades Mount Arapiles, in western Victoria, has been the focus of traditional climbing in Australia, with its thousands of routes above the Wimmera plains attracting a global following.

But indigenous groups will soon begin a heritage survey of the area, which will almost certainly show a strong historical connection that could trigger restrictions on climbing. The survey will follow Parks Victoria imposing cultural heritage bans across large areas of the nearby Grampians National Park, closing an estimated 500sq km to climbing, leading to chaos in the industry and undermining adventure tourism.

Barengi Gadjin Land Council chief executive Michael Stewart said it would be up to the traditional owners to determine what to do if it was established that climbing occurred in culturally sensitive areas.

“If the particular activity is running at that site, the Aboriginal Heritage Act is pretty prescriptive about what can and can’t happen at a site,’’ Mr Stewart said.

“And if an activity is harming a site, then anyone undertaking that activity and anyone that allows that activity is generally seen to be in breach of the act.’’

Climbers at the Grampians have been told that penalties of up to $1.6 million can apply to groups that fail to protect indigenous heritage, such as rock art. The legislation also appears to leave open the prospect of multiple penalties for multiple offences. Climbers believe Parks Victoria’s potential exposure to the fines is driving the Grampians bans.

A row has also broken out over the decision to close Uluru to walkers from October 26 because of cultural sensitivies and the spiritual significance of the rock to the Anangu people.

Mr Stewart said the Mount Arapiles survey had been sparked by the Grampians bans and would help make informed management decisions.

Mount Arapiles, 330km northwest of Melbourne, has an extensive indigenous history covering large parts of the mountain and nearby Mitre Rock. Climber John Fischer, who came to the town of Natimuk and Mount Arapiles via the US, said climbers constantly engaged with indigenous groups and were alive to the history.

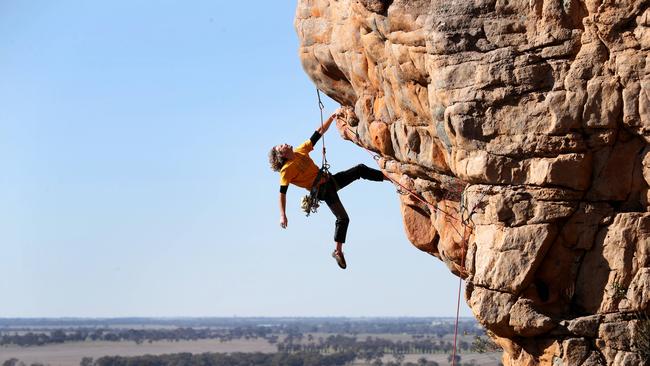

“Arapiles is the heart of traditional climbing in Australia,’’ Mr Fischer said. “If we lose Natimuk, we lose the chance to connect to country, place and respect indigenous culture.’’

Parks Victoria, which oversees the Mount Arapiles-Tooan State Park, did not respond to questions about whether it would protect climber access or whether it was concerned about the potential impact on climbing at Mount Arapiles.

“Parks Victoria is aware of the need for a cultural heritage assessment to be conducted at Mount Arapiles,’’ a spokeswoman said. “Ongoing updates and revision of information and data across the estate is critical in making informed management decisions. We take our responsibilities to protect and conserve the state’s natural and cultural values seriously.’’

Australian Climbing Association of Victoria spokesman Mike Tomkins said climbers wanted to be involved with any survey to help the traditional owners. “ (Arapiles) is world-famous, it’s much loved around the world. It’s a climbing location that suits everyone from beginner to expert,’’ Mr Tomkins said.