For Chieften, a future Indigenous vision emerges at last

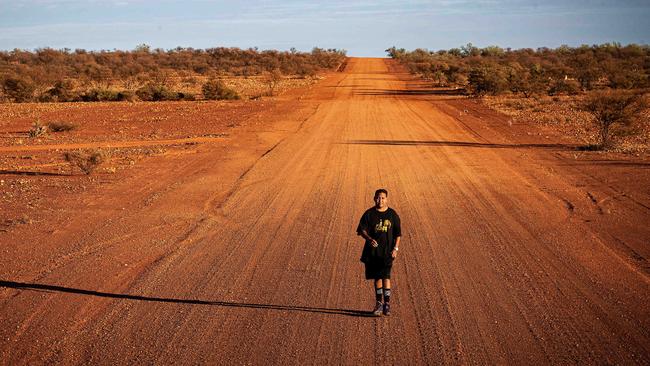

Justin Corbett and Delenn Dowden grew up together in Meekatharra, the outback town Malcolm Fraser’s wife Tamie famously called ‘the end of the earth’.

Justin Corbett and Delenn Dowden grew up together in Meekatharra, the outback town Malcolm Fraser’s wife Tamie famously called “the end of the earth”. Her remark made news when the Frasers were stranded there in 1978 after their plane was forced to land. Mrs Fraser returned to Meekatharra the following year as an act of goodwill but visits from politicians remain uncommon.

Mr Corbett, 25, does not expect that to change. Meekatharra is more than 3000km from Canberra and neither fish nor fowl for policymakers.

But Mr Corbett and Ms Dowden, 22, are happy raising their son Chieften here on the West Australian rangelands between the wheatbelt and the desert.

They are proud that he is a bright, curious child living close to nature and surrounded by the love of his Indigenous elders. Mr Corbett, who works for a local Aboriginal corporation, takes the toddler hunting at least once a week. They look for kangaroo, emu and goanna, and share the meat with the old people in town. “It’s a good little place,” Mr Corbett says. “This is what we want for our boy now, but we do worry a bit about what the future has for him if we stay here.”

Lately Chieften has been fixated on dinosaurs and roars like one as he plays for hours with his triceratops figurine. But his dad says that in Meekatharra, kids often go off the rails as teenagers. They get into alcohol, drugs and stealing. Mr Corbett is grateful that as a teen he had the guidance of his grandfather, who raised him after his mother died.

“The teenagers need opportunities,” he said.

The town has little in common with bigger regional centres but it is not a remote Aboriginal community either. The town’s social problems are especially serious for Aboriginal residents, who make up about a third of the population of 1076 permanent residents. The scourge of alcohol and other social problems are largely unseen by the rest of Australia.

Mr Corbett and Ms Dowden have clear ideas about what needs to change. Under the proposal for an Indigenous voice, the experiences and suggestions of Aboriginal people in remote and regional areas would reach the politicians who never come to town. If the proposed models in the report published on Saturday are adopted, couples such as Mr Corbett and Ms Dowden could be sitting down with government officials to make decisions about how and where money is spent in their community. It is a concept that surprises Jimayne Dowden, 18, and Delenn’s nephew, who works at the Coles Express in Meekatharra.

“The biggest issue here is boredom,” he said. “Kids get bored then they get in trouble.”

Mr Dowden is preparing to start a job at a goldmine close to home after a difficult few years. His grandmother, who raised him, died from complications of diabetes. Then, aged 15, he felt the responsibility of trying to support his father, who was struggling with an addiction that led to jail. Mr Dowden’s steadiest influence through the grief and tumult has been his grandfather Steve Beeson.

Mr Dowden does not say an Indigenous voice would have helped him then. Mr Beeson said governments should know that, tucked away in towns like Meekatharra, Indigenous children are dealing with big challenges.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout