Fitzroy River offers riches but not everyone’s on board

There are growing fears that, incrementally, WA’s Fitzroy River could become a mess in the order of the Murray-Darling.

At every opportunity, 14-year-old Shanen Gardner is at Geike Gorge in the far north of Western Australia, fishing or swimming.

There are freshwater crocodiles around but none of the deadly salties that lurk in waterways closer to the coast. Shanen lives 12km from the gorge that sustained his ancestors with bream, barb fish, yabbies and the sawfish that is now critically endangered. “Barramundi is my favourite,” he says.

Now the future of the 730km river that feeds the gorge is being discussed in heated tones in the state’s north.

Some pastoralists describe the mouth of the Fitzroy River as Australia’s biggest salination plant, turning vast quantities of clean water to salt every hour as it empties into King Sound near the port of Derby. The river was already flooded in early March when more rain sent 500,000 megalitres downstream past the town of Fitzroy Crossing towards the coast, according to the Department of Water and Environmental Regulation.

WA Labor ministers are listening to the argument that drawing water from one of Australia’s most iconic waterways could create jobs, make more of under-utilised pastoral leases and drive indigenous enterprise. Across the Fitzroy Valley, where half of all residents are indigenous, unemployment runs at 31 per cent.

The negotiations have been complex and difficult, but WA Regional Development Minister Alannah MacTiernan believes it is possible to find common ground with Aboriginal people and cattle barons about a plan to take surface water in the wet season between December and March.

She told The Weekend Australian her government was still “waiting on the science” for a definitive percentage of what could safely be taken but she predicted it would be no more than 5 per cent of total flow.

Under the plan being discussed, native title holders in the valley would receive a third-share of the water taken from the Kimberley’s most important waterway, the Fitzroy River. They would be free to use that share to run their own horticultural or agricultural businesses or sell to pastoralists to fund other economic ventures.

The remaining two-thirds would be shared among pastoralists in the valley, including billionaire Gina Rinehart, Chinese interests and Aboriginal corporations with significant horticultural and agricultural holdings.

The McGowan government is sticking to its 2017 election promise that no dams will be allowed, drawing a line under Liberal government plans in the 1980s to dam the Fitzroy.

This promise is greeted with scepticism by indigenous elders including Mary Aiken, a Bunuba woman who grew up fishing the river with string from flour bags, saddlery needles shaped into hooks and salted meat from the United Aborigines’ Mission kitchen. She went to school in a cave on Gogo Station, now joined to Cherrabun station to form a 460,000ha holding of the Harris family, which has a long history growing cotton in NSW.

She knows every creek and bore in the valley and how the landscape has changed.

She understands the modest proposals under consideration but fears that incrementally the Fitzroy River could become a mess in the order of the Murray-Darling. “What frightens me is this could be the start of something very bad,” she said. “After I am gone, another government could dam this river. You just don’t know what could be allowed once it starts.”

These are the fears at the heart of a campaign by Environs Kimberley, a lobby group that in 2011 helped kill off a proposed gas hub in the Kimberley.

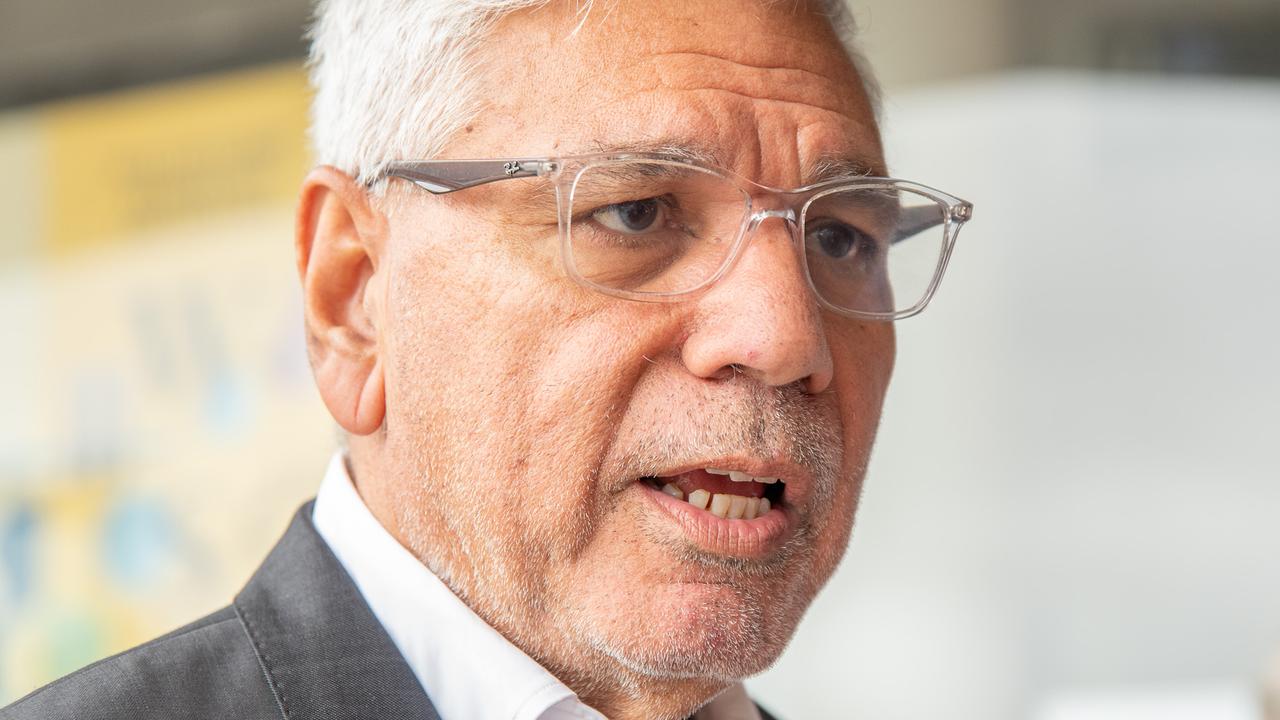

Nykina man, lawyer and former Kimberley Land Council head Wayne Bergmann wanted the gas hub and the $1.5bn benefits package for indigenous people, but is opposed to widespread development of the Fitzroy River. He speaks as the chairman of an Aboriginal cattle company. He says he grew up with his grandparents “taking me fishing and hunting all along the river. I want my kids to grow up experiencing the same things.

“The cost-benefit of widespread development on the river is not justifiable. The only people who are standing to benefit from economic development are those who are already wealthy.

“There should be no development on the Fitzroy, there should be no extraction of water.”

There are a few indigenous-run cattle operations that are reserving judgment. On the other side are major pastoral leaseholders who want access to large amounts of water to grow grain and feed for cattle. Those who stand to gain most are big names in the game. Mrs Rinehart’s Hancock Agriculture owns Kimberley cattle properties Liveringa, Nerrimah and Fossil Downs stations, and wants access to 325 billion litres of water a year to grow cattle fodder on 21,500ha. That amount is more than the two million residents of Perth and the southwest used in 2017.

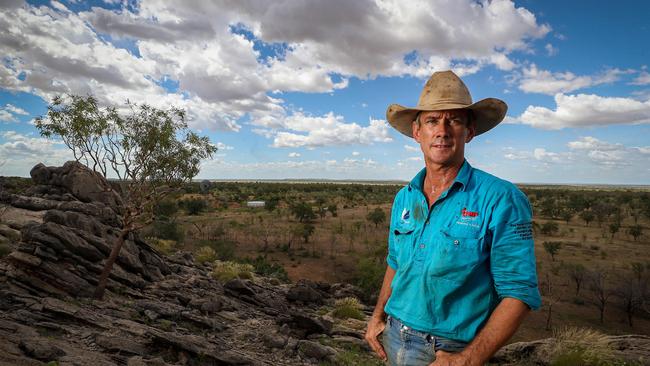

Further east, at Gogo Station, the Harris family has been irrigating with groundwater in recent dry years and asks for an allocation from the river with strict conditions; during flood only. According to station manager Chris Towne, this would mean finishing cattle on the station and exporting them out of nearby Derby rather than having to truck them 2500km to greener pastures near Perth for the final months before sale. The author of Gogo Station’s proposal, Philip Hams, sees local jobs in the plan. He also says the “no flood, no take” condition would likely mean Gogo would not get an allocation about three years out of 10.

The Kimberley Pilbara Cattlemen’s Association is a keen advocate of using river water, on sustainable terms. “We have an opportunity to get this right,” says KPCA chief executive Emma White, who rejects the claims it will see a repeat of the problems of over-allocation and water warehousing seen in the Murray-Darling system.

“It’s always important to learn from what’s gone on before,” she says. “But the Murray-Darling is multiple jurisdictions and it hasn’t had strict use-it-or-lose it principles. This is one jurisdiction and a very different case. And no water can be taken from the river until it reaches a certain level.”

There are 48 pastoral leases in the Fitzroy Valley region, but only eight are close to the river. The “vision splendid” is for those in semi-wilderness to clear land, turn on the tap and irrigate vast areas for fodder crops for cattle, and other crops such as cotton. The cotton option is particularly attractive, says Ms White. “Ord River growers (further north) are watching the Fitzroy Valley issue to see if it is opened up, because it’s more productive land. And cotton seed is edible to cattle.”

Ms MacTiernan is keenly aware that what she calls the “disaster” of the Murray-Darling makes the negotiations in WA difficult, though she stresses there is no comparison given the modesty of what is being proposed. She knows whatever is decided must be backed by the majority of native title holders or it will fail.

She said the final plan would preserve and respect Aboriginal people’s cultural and environmental concerns. “If we are going to actually achieve any transformation in the lives of Aboriginal people, we need to bring them with us,” she said. “This can’t be something that is imposed on indigenous people.”

More Coverage