Closures vindicate my stand, says Colin Barnett

Colin Barnett says he’s not surprised those who opposed closures of remote communities have quietly shut them down.

Former West Australian premier Colin Barnett says he is not surprised that the same MPs who opposed his proposed closures of remote indigenous communities have now quietly shut down 25 such settlements.

The Australian on Monday revealed that WA’s Labor government had suspended essential services at communities in the far north Kimberley — just five years after Mr Barnett and his Liberal government suffered a political backlash over a similar proposal.

Mr Barnett’s plan sparked mass protests, a rebuke from the United Nations, and fierce criticism from the state Labor opposition when he announced in 2014 that many of the state’s 274 remote communities would close.

On Monday, he told The Australian the Labor government’s move confirmed that funding many of the remote communities could not be justified.

“It became very clear to me that in some of the smaller communities there was not proper management, they were not viable, there were no opportunities for young people, and education and health levels were poor,” Mr Barnett said.

“If we were to do better in terms of child protection and employment opportunities and schooling and health, we needed a smaller number of large communities.”

Among the critics of Mr Barnett’s plan was Ben Wyatt, who is now WA’s Treasurer and Aboriginal Affairs Minister.

Mr Wyatt said at the time that Mr Barnett had created “ongoing uncertainty, confusion and fear” in remote Aboriginal communities.

Mr Barnett said on Monday that many of the remote communities he had planned to close had only a handful of homes and were often occupied only during the winter months.

He said his chief concern had been for children, saying there had been a disproportionate number of instances of child abuse in some of those settlements.

“It was inevitable and I hope we can see more viable and stable Aboriginal communities develop,” he said.

The 2014 decision also followed a move by then prime minister Tony Abbott to cut federal government funding for the communities. The federal government had previously paid half the costs of maintaining the remote settlements.

WA Housing Minister Peter Tinley cited the end of the federal government’s funding as a key challenge to services in remote communities, saying in a statement that the decision had left an ongoing annual $100m hole in the state budget.

The McGowan government is investing heavily in 10 of the state’s largest remote communities, including by installing sewerage and water systems that residents will for the first time be billed for.

It is also helping indigenous families move off dilapidated town camps into new or refurbished homes in the suburbs in a program called Move To Town.

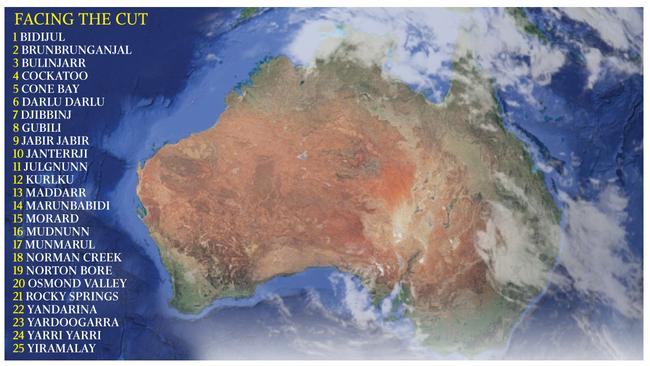

The list of communities that have had services suspended includes Osmond Valley at the foot of the Bungle Bungles, where flood, then fire, drove residents away several years ago, and Kurlku in the Great Sandy Desert.

Kurlku, which was established by the late artist Jimmy Pike in the 1980s, has no permanent residents.