Income tax ‘to top half a trillion’

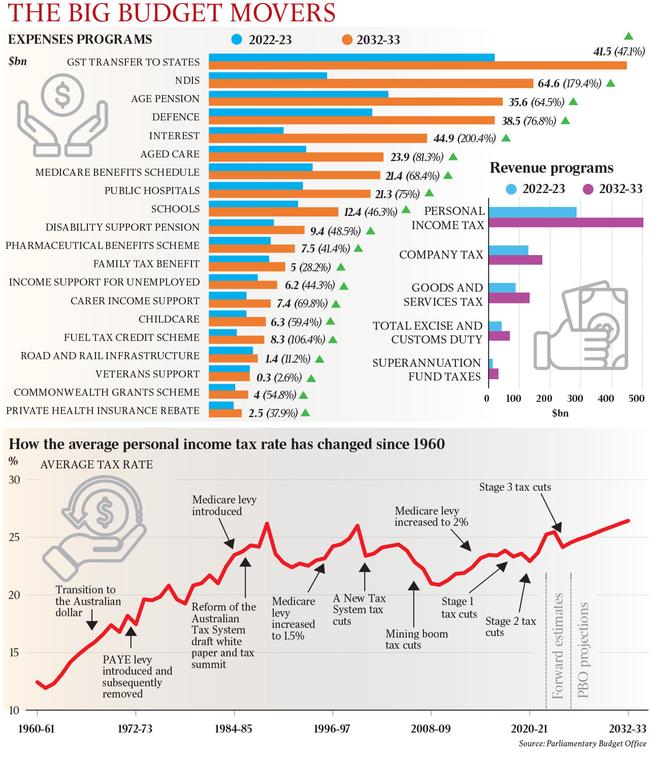

The personal income tax take will account for half of all commonwealth government revenue in a decade, new analysis reveals.

The personal income tax take will surge to half a trillion dollars and account for half of all commonwealth government revenue in a decade, new analysis from the federal budget watchdog says.

The Parliamentary Budget Office research highlighted the risks of relying too heavily on one form of tax income, particularly in an ageing society with a falling proportion of working-age contributors.

The PBO’s Beyond the Budget report estimated that the average personal income tax rate would lift from 23.7 per cent in 2021-22 to 26.4 per cent in 2032-33 – the highest in records stretching back to 1961.

“Bracket creep has played an important role in fiscal consolidation after major downturns in the past,” the report said, noting that average tax rates and total tax revenue were allowed to move higher in the wake of the 1990s recession and the GFC, helping to improve the budget position.

“However, too much reliance on a single revenue source can generate risks to the budget,” it said. “Higher average tax rates can magnify the economic impacts associated with personal income tax. For some people, especially those on relatively low incomes, bracket creep can reduce workforce participation.

“At higher incomes, bracket creep can strengthen incentives for tax planning and structuring.”

The last time personal income tax accounted for one in every two dollars of federal government revenue was immediately before the introduction of the GST, suggesting that without action, bracket creep by the start of the 2030s will have undone all the hard work put in at the beginning of the century to broaden the tax base.

“There is an important trade-off between fiscal consolidation, aided by bracket creep, and minimising the risks associated with relying on a single source of revenue,” the PBO report said.

The commonwealth is carrying a deep structural deficit as a result of ballooning costs of social services, defence and servicing a record debt pile accumulated through the pandemic.

The PBO report estimated that the annual cost of the NDIS would nearly triple to more than over $100bn in a decade to be the single most expensive federal program, accounting for nearly 10 per cent of recurring outlays.

The analysis suggested we would be spending five times more on supporting the disabled through the NDIS than on unemployment benefits, and twice as much as on Medicare.

The next most expensive programs would be the $90bn spent annually on Age Pensions and on defence.

The other largest increase in costs over the coming decade would be on servicing the national debt, which in gross terms would pass $1 trillion for the first time in 2023-24 and be approaching $1.8 trillion by 2032-33.

Higher debt and borrowing costs meant interest costs would surge from $22bn in 2022-23 to $67bn 10 years later.

Despite a structural deficit of 1.7 per cent of GDP – or about $65bn – the PBO found that “the fiscal position is sustainable in most scenarios” over the coming decades.

“This means that future governments should be able to keep debt-to-GDP relatively stable through interventions on a similar scale to what we have seen in the past,” the report said.

“However, there are structural risks to the budget, including the ageing population and the climate change transition, that may increase the extent to which governments would need to intervene to keep the fiscal position sustainable.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout