History of disasters shows there is nothing new about nation’s destructive blazes

The blazes that continue to plague the eastern states and Western Australia are nothing new.

While there is no doubt these bushfires are bad and may get worse, fuelling more talk of the nation battling an unprecedented fire threat this summer, the blazes that continue to plague the eastern states and Western Australia are nothing new.

They do not compare with some of the more extreme fire disasters in Australia’s short history, such as the Black Thursday conflagration of 1851 that burned five million hectares and was so intense that ships 30km off the coast of Victoria reported coming under ember attack.

Those fires covered one-quarter of what is now the state of Victoria, including the Portland region, the Plenty Ranges, the Wimmera and Dandenong. Twelve people died and one million sheep perished.

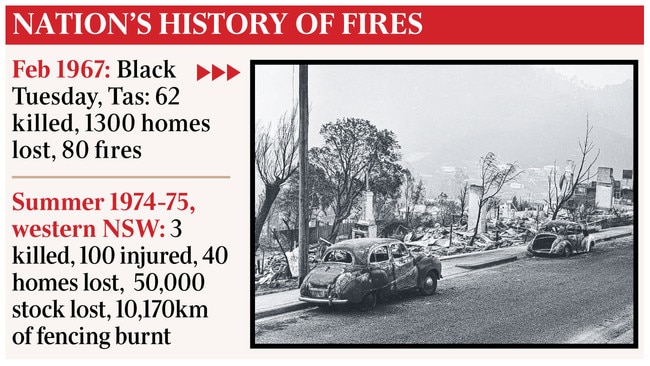

Then there have been the more recent blazes in which scores of lives were lost. Geoscience Australia estimates that between 1967 and 2013, major bushfires killed 433 people, injured another 8000 and caused $4.7bn in damage.

Among them were the blazes that swept across NSW and other states in the summer of 1974-75, the worst bushfire system the nation had faced in 30 years. Although there were just three deaths and about 100 injuries attributed to the fires, the Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience estimates about 15 per cent of Australia’s physical landmass, about 117 million hectares, had extensive fire damage.

Much of the fire threat was in the sparsely populated far west of NSW, yet property damage was extensive: 50,000 stock lost and 10,170km of fencing destroyed, according to the NSW Rural Fire Service. The fire burned 1.5 million hectares in the Cobar shire and 340,000ha in the Balranald shire.

Then there was the Moolah-Corinya fire that the NSW Rural Fire Service says was the largest ever to be put out by firefighters at the time. The perimeter was more than 1000km.

In the late 1970s, it was the Blue Mountains’ turn. It weathered two bad fire seasons. In late 1976, 65,000ha were burnt. The following year another 54,000ha went up, one life was lost and 49 buildings destroyed.

Two years later the Southern Highlands was hit by major fires and the next year fires burnt more than one million hectares in total across NSW.

Climate change or no, these are some of the costs of being in one of the most fire-prone regions of the world. And those costs have been paid since well before Federation.

Indeed, of the entire list of official inquiries detailed in the AIDR’s bushfire and natural hazards database, just two make recommendations about factoring in climate change as part of the response to future fire risks.

This is not to reject the notion that climate change has played no role at all in the present bushfire threat. A major study into the variability of Australia’s fire weather between 1973 and 2017 by the Victorian Country Fire Authority’s Sarah Harris and the Bureau of Meteorology’s Chris Lucas found there was a long-term upward trend in fire weather with the strongest trend found in southern Australia, in spring. “This long-term trend is likely mostly due to anthropogenic climate change,” the authors note in their report, published in September.

They go on to argue that “accepting that anthropogenic (human caused) climate change is the most likely cause of the upward trend of fire weather in some parts of Australia will enable policymakers to make longer-term decisions around managing fires in a changing climate”.

But, as the examples before attest, fires will always start in Australia. Those involved in the actual fighting of these fires say it is reducing the fuel the blazes need to keep burning that holds the key to getting on top of them.

In a review of Queensland’s recent bushfire experience, the Inspector-General of Emergency Management, Iain Mackenzie, had this to say: “The office heard from associations representing bushfire managers who conveyed ‘indisputable facts’ about vegetated areas and their management.

“Their points were that fires will always start, and that fire management relies on, and must be led by, managing and reducing fuel. Climate change, they said, had not influenced the past build-up of fuel; some fires are best left to burn, and response will only be effective if preparation and mitigation have been effective beforehand.’’

While acknowledging that there needs to be a compelling narrative around climate change and its effects regarding bushfire risk (the phrase is mentioned nearly 100 times in his review), Mackenzie found “that fuel, and management of fuel loads, should be the key focus of bushfire mitigation”.

There are many ways a bushfire can start, including dry lightning, accident, careless burning and, arson. But for a bushfire to take hold, it needs fuel, high temperatures and low humidity. The factor that most concerns governments, landowners and others charged with managing fire risk is fuel load.

Queensland’s rural fire service assistant commissioner Tony Johnson agrees that while conditions this summer are not unprecedented, there is more political and media focus on the fires than 25 years ago when similar circumstances — a long drought, high fuel loads, higher temperatures — confronted the state.

Echoing Mackenzie’s focus on management of fuel loads being key to mitigating against fires, Johnson says it is important to understand that the behaviour of communities also needs to be taken into account in better managing bushfire risk.

‘‘There is a combination of factors contributing. It’s hard to blame it all on just climate change because there are a number of factors at work,” he said.

“People change farming practices, they change crops they plant. In urban areas people like vegetation between houses, they have bigger houses, bigger roofs.

“These all reflect heat into vegetation that dries out and you have fuel.”

The biggest fires in terms of area burned are actually in low-population areas of the Northern Territory, Western Australia and north Queensland.

It is when fires occur in populated areas that the explosive combination of high fuel load and proximity of homes becomes most apparent.

Little wonder many fighting such fires are more concerned about the fuel that keeps them burning than political debates.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout