High Court rules on new status for indigenous people

The decision means indigenous people, even those born overseas, cannot be considered ‘aliens’ and deported on character grounds.

A landmark High Court ruling has found indigenous people — even those born overseas — cannot be considered “aliens” under the Constitution and deported on character grounds.

The 4-3 split decision on Tuesday was described by the Morrison government as creating “a new category of persons”, while constitutional lawyers said it could create “special rights or privileges” for Aboriginal people.

Two indigenous men who were born overseas and are not Australian citizens faced deportation after failing migration character tests as a result of committing separate violent assaults in Australia.

In a majority decision, the High Court found Aboriginal people cannot be classified as “aliens”, regardless of whether they held Australian citizenship or not.

Acting Immigration Minister Alan Tudge said the ruling had created a category of persons who were “neither an Australian citizen under the Australian Citizenship Act, nor a non-citizen” and the government would review other cases that might be impacted.

The judgment was praised as affirming how Aboriginality should be recognised, and criticised as the “most radical instance of judicial activism in Australian history”.

Judges Virginia Bell, Geoffrey Nettle, Michelle Gordon and James Edelman ruled that the tripartite test of biological descent, self-identification and recognition of Aboriginality by a traditional group — established by the Mabo native title cases — meant Aboriginal people “are not within the reach of the ‘aliens’ power conferred by the Constitution”.

The majority of judges recognised a third category of person exists — someone who is neither an alien nor a citizen.

Writing in The Australian, constitutional law expert Anne Twomey says the most contentious aspect of the judgment is whether it creates “special rights or privileges” for Aboriginal people and creates a race-based constitutional distinction.

While Justice Gordon “pointed out that the Constitution does not prohibit special treatment of a race” and Justice Edelman noted that “equality is not about treating everyone the same”, Professor Twomey predicts the issue will be a matter of ongoing debate.

She also cited Justice Edelman’s discussion of the “powerful spiritual and cultural connections Aboriginal people have generally with the lands of Australia” as an “underlying fundamental truth that cannot be altered or deemed not to exist by legislation”.

The decision signalled a major victory for one of the defendants, Brendan Thoms, who was released from a Brisbane detention centre on Tuesday after spending nearly 500 days behind bars.

The panel of High Court judges was unable to decide on whether Mr Thoms’s fellow defendant, Daniel Love, who was born in Papua New Guinea but grew up in Australia, is Aboriginal and ordered a further hearing to investigate.

Mr Love was sentenced in May 2018 to 12 months behind bars for assault occasioning bodily harm. Mr Thoms was convicted of a domestic violence offence in September 2018, for which he received an 18-month sentence.

On serving their sentences, the men had their visas revoked and were taken to a Queensland immigration detention centre and told they would be deported. They are seeking damages for false imprisonment.

While neither man holds Australian citizenship, each has an Australian parent and identifies as Aboriginal. Mr Love is a PNG citizen, and Mr Thoms a New Zealand citizen.

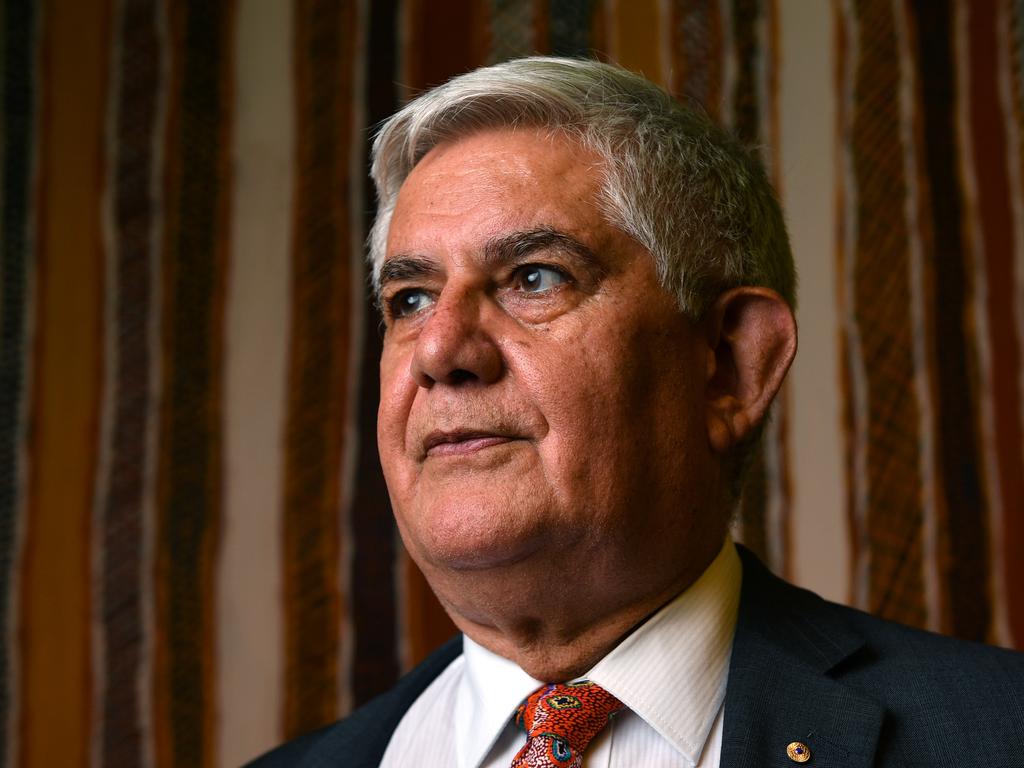

Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt said he was pleased the finding reaffirmed the “tripartite way” of recognising Aboriginality.

“That is biological evidence, recognised within the community and identifying within the community,” Mr Wyatt said.

“That has been a constant right through in the High Court … and is consistent with the Mabo decision.’’

Chief Justice Susan Kiefel said it was “erroneous” to apply the connection to land required in native title cases to an “entirely different area of the law”.

She differed with the majority in stating that a mechanism, by which Aboriginal communities would have the power to determine when normal migration laws will apply, “would be to attribute to the group the kind of sovereignty which was implicitly rejected by (the Mabo decision)”.

Law Council of Australia president Pauline Wright welcomed the decision, saying the finding flowed from the Mabo case of 1992.

“This … confirms that the question of membership of Aboriginal societies is outside of the legislative power of the Australian parliament,” she said, acknowledging the finding would be the subject of “much scrutiny and comment”.

Institute of Public Affairs research fellow Morgan Begg said the decision was “absurd” and the “most radical instance of judicial activism in Australian history”.

Last year, the pair’s barrister, Stephen Keim, invoked Mabo, saying: “To remove Aboriginal Australians from the country would be another, if not worse, case of dispossession.’’ The High Court ordered the commonwealth to pay the men’s legal costs.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout