Test cases risk NDIS budget blowout

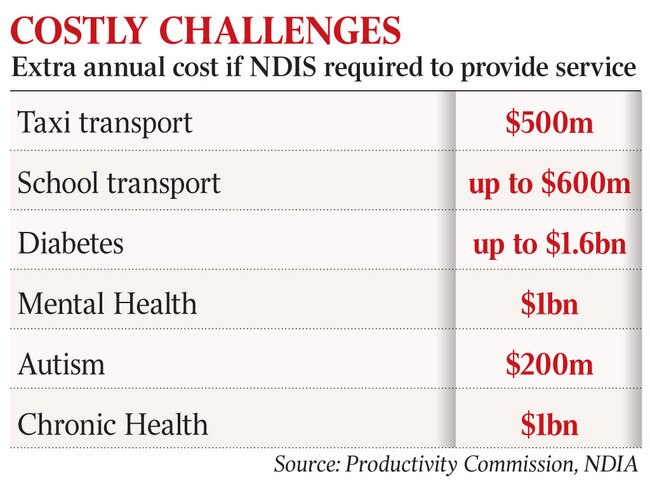

A decision to force the NDIA to fund registered nurses for diabetics would blow the budget by up to $1.6bn each year.

A decision to force the National Disability Insurance Agency to fund registered nurses for diabetics would blow the budget by up to $1.6 billion each year, by its own estimate, as the program loses significant cost-shifting battles with state governments and the courts threaten its viability.

More than five years after the $22bn landmark scheme began, bureaucrats remain locked in tense negotiations with the states and territories about who should pay for health services, transport, out-of-home care and autism services while courts and tribunals pick holes in “ill-defined” legislation.

The total value of additional costs for the scheme could top $5bn each year if the NDIA continues to lose test cases, based on estimates from the Productivity Commission, government agencies and participant data.

Australian Lawyers Alliance spokesman Tony Kerin said NDIS executives viewed unfavourable judicial decisions as “opening the floodgates”.

“They are either going to have to find more money to fund the thing properly, somehow, or they will have to narrow the eligibility criteria,” Mr Kerin told The Weekend Australian.

“They are losing more cases now than they are winning, by a long shot.”

In August, the NDIA lost three major cases that went to the core of its ability to keep a lid on costs, and in one matter refused a subpoena to appear in court and produce documents, putting it dangerously close to contempt of court.

In a case before the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, Kim Mazy — a 53-year-old blind, deaf and intellectually disabled woman — appealed an NDIA decision to refuse funding for insulin injections administered four times a day by a registered nurse.

The AAT reversed the decision, requiring the scheme to fund the annual $38,000 service from Nurses on Wheels, which receives some state and federal government funding. The decision is significant because, in a previous matter, the agency estimated the cost of providing support for an approximate 40,000 people with Type I diabetes in the scheme would be “between $1.3bn and $1.6bn”. In an earlier report, The Australian revealed the case of another woman who had been living in a public hospital in Sydney for more than six months because the NDIS would not fund the same Nurses on Wheels service for her insulin injections.

The agency also ignored an earlier decision by the full bench of the Federal Court of Australia and attempted to argue against paying the full transport costs of severely disabled 26-year-old Luke David. The agency said rather than Mr David attending work, sports club meetings and socialising with his friends in person he should do this from home via “telephone, email or Skype”.

The AAT overturned the decision and doubled his annual transport funding to more than $12,000. In its own submission to the Productivity Commission review of scheme costs last year, the NDIA said the risk of legal interpretations in the courts to the financial viability of the program was “potentially extreme”.

A spokesman for Social Services Minister Paul Fletcher said: “The government and NDIA closely monitor decisions of the AAT to ensure the long-term sustainability of the scheme. All governments are working together through the Disability Reform Council to ensure the appropriate division of roles and responsibilities between the NDIS and other mainstream service systems.”

Systems that used to be the responsibility of state governments — including education, corrective services and foster care — have had their funding revised under Gillard-era deals when the states calculated their contribution to the NDIS.

In late August, the agency also lost its bid to recoup compensation from a disabled woman in the Supreme Court of NSW because it had no grounds to do so under the legislation.

Judge Julia Lonergan noted “for reasons that are opaque to analysis”, the NDIA had tried to at first claim $34,000 and then $136,000 before revising the figure to $106,000. A “proper officer” of the agency was subpoenaed to produce documents relating to how those figures were devised and to attend court to explain them.

“I had the proper officer of the NDIA called three times outside the court, there was no appearance,” Judge Lonergan says in her decision. “I have been informed by counsel for the plaintiff that no documents have been produced in response to the subpoena returnable again today, and that no courtesy of attendance or acknowledgment or appearance by the proper officer or a legal adviser on behalf of the recipient of the subpoena has been extended.

“It seems to me, on one analysis, this could be considered to be contempt of this court’s process on the part of the NDIA.”

Senior lecturer in administrative law at La Trobe Law School Darren O’Donovon said the NDIS Act had “revealed a problematic lack of express definitions and a number of interpretative gaps”. “For instance, the core terms of ‘condition’ and ‘impairment’ are not defined, creating an irritating circularity,” Dr O’Donovon wrote on the AusPubLaw blog.

The Productivity Commission has also noted that while the whole scheme turns on “reasonable and necessary” support for participants, there is no definition of this term in the legislation. Mr Kerin said “the only way to really get rid of some of these decisions is to keep appealing them, which costs too much money”. “They passed broad legislation to get the stuff through parliament and put all the power in the rules (which require majority or unanimous agreement with states to change) so there is a long way to go with this scheme before that is all ironed out,” he said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout