Bid to strip rort doctors’ cars, houses

Doctors suspected of rorting Medicare could lose their luxury houses and cars, under a dramatic escalation of compliance efforts.

Doctors suspected of rorting Medicare could lose their luxury houses and cars, under a dramatic escalation of compliance efforts tipped to raise tens of millions of dollars a year for the federal government.

The Department of Health has asked the Australian Federal Police whether the Proceeds of Crime Act — commonly used to restrain the assets of drug dealers, money launderers and fraudsters — could help it to deal with errant doctors.

The department has often struggled to recoup more than 30 per cent of the Medicare rebates it could prove were misused but was recently given new powers, including the ability to act against doctors who refused to co-operate. Utilising the Proceeds of Crime Act would be likely to reverse the onus of proof, and require the doctor to argue they did not deserve to have their assets restrained or seized to repay Medicare rebates.

A department spokeswoman confirmed the AFP had been asked for advice on how assets could be confiscated and sold to clear debts. The Proceeds of Crime Act has been used for a range of assets including real estate and commercial property, share portfolios, luxury cars, jewellery, motorcycles, light planes, jetskis, yachts and motor boats, artwork and other collectibles.

“The Department of Health has recently begun working with AFP to help identify matters where POCA could be well utilised,” the department spokeswoman said.

It was unclear whether the act could be used only against the holder of a Medicare provider number or also against their employer. The AFP did not respond to requests for comment.

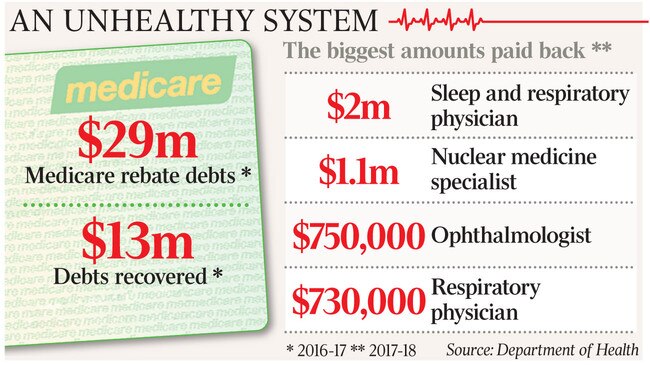

In 2016-17, the department recorded up to $29 million worth of debts against doctors and other healthcare providers but recouped only about $13m of that. At the time, Medicare was paying out $22 billion in benefits, and health officials suggested Australia was below the international benchmark of 1 per cent of expenditure raised as debts and recovered.

The Professional Services Review, a peer-review agency that acts on referrals from Medicare, often deals with doctors administratively, negotiating agreements where individuals voluntarily pay back some money. It can refer suspected fraud to police, where a conviction could lead to civil action to recover government funds, however such action is rare.

In 2016-17, the largest repayment negotiated by the PSR was $1.1m, however last financial year a consultant sleep and respiratory physician agreed to repay $2m, a nuclear medicine specialist $1.1m, an ophthalmologist $750,000 and another sleep and respiratory physician $730,000.

The nature of current arrangements means the published Medicare debts are only a fraction of the amount the department suspects to have been misused.

In the 2017-18 budget, amid efforts to make health spending more sustainable, the government announced plans to ramp up compliance efforts and recoup an additional $103.8m over four years. New legislation came into effect in July, including tougher record-keeping requirements and the power to order the provision of documents.

Explanatory documents for the legislation did not mention the Proceeds of Crime Act but argued that stronger powers were needed so that the government could recover more of the funds that have been overpaid because of incorrect claiming, inappropriate practice and fraud”. The department can offset or deduct all or part of a debt from the bank accounts of the person owing the money to Medicare or, in some cases, a third party. It can also reduce their future bulk-billed payments by up to 20 per cent.

Under the legislation, a shared debt-recovery scheme is expected to commence next July, allowing the department to hold a clinic, hospital or corporate entity responsible for debts incurred under an individual’s Medicare provider number.

The government has yet to revise its financial forecasts for the new compliance regime or any Proceeds of Crime Act cases. The debt-recovery rate was most recently estimated to be 40 per cent, but the department could also pursue a broader range of matters under threat of recovery action.

The AFP’s Criminal Assets Confiscation Taskforce restrains about $100m in assets each year. The proceeds are placed into the Confiscated Assets Account and distributed by the government. The department would probably require any Medicare-related proceeds to be reinvested in the health system, as currently occurs in compliance matters.

While the department pursues individual cases, there is no centralised mechanism across government for recording health debts to the commonwealth or ministerial waivers of such debts. The Department of Finance this year denied a Freedom of Information request from The Australian for details of debts waived over a six-month period.

More than 87,000 people are on the immigration watchlist because they left debts to the commonwealth, including for health services they obtained while in Australia despite not being eligible for Medicare. The list would also be likely to include overseas-trained doctors who left the country with unresolved Medicare issues.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout