100,000 children on pills for depression

The number of Australian children on antidepressants has doubled to more than 100,000 in six years.

The number of Australian children on antidepressants has doubled to more than 100,000 in six years, prompting some of the nation’s most experienced clinicians to warn that the nation is facing a mental health “iceberg’’.

The soaring demand reflects a growing community appetite for early intervention in the treatment of mental health and the rise in public awareness about depression.

But there are fears that the $9 billion sector’s treatment strategies for the social-media generation are compromised by a lack of accurate research data and limited resources.

It is broadly accepted in the mental health sector that there is a valuable role for antidepressants in the treatment of some children. However, experts are questioning whether there is sufficient support for other services — such as psychology — to buttress and precede the use of medication.

Medical professor Ian Hickie of the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre said there were significant socio-economic factors at play, with affluent areas in Sydney and Melbourne having access to good psychological services, but which can be costly.

However, he said services could be mixed in other, less affluent areas. This could lead to doctors prescribing more antidepressants in areas where patients could not afford the gap payments for psychological therapy.

“Medicines go up where psychological therapies go down,’’ Dr Hickie told The Weekend Australian.

Of the mental health scourge, he said: “I say we are still getting to the tip of the iceberg.’’

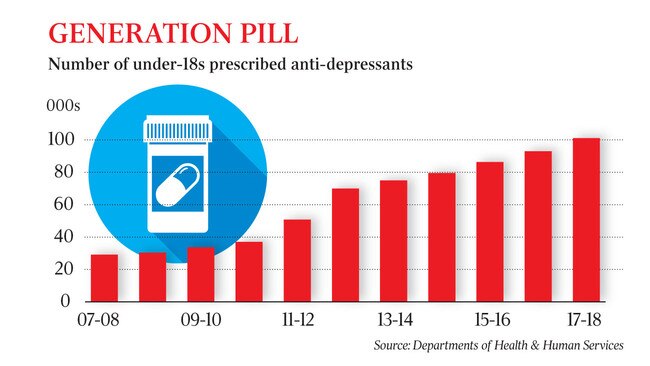

Child antidepressant recipients in Australia soared 100 per cent from 50,804 in 2011-12 to 101,174 last financial year, according to the Department of Human Services.

It marks the first time that the number of children taking antidepressants has breached the 100,000 mark.

The department partly attributed this stark increase to a change in the way data was collected, with so-called under co-payment prescriptions now included in the numbers.

The supply of antidepressants has increased across all age groups since 2012-13, based on the raw numbers and rates per capita, the department data shows. But the younger cohort is growing at a faster rate than older age groups.

The DHS data shows an even more stark lift in the raw numbers of young antidepressant users in the past decade, with fewer than 30,000 children taking the drugs in 2007-08.

The increase in child mental health patients also comes as parents and schools grapple with the rise of social media and gaming technology, which has transformed the way children are taught and entertained.

ANU Centre for Mental Health Research fellow Sebastian Rosenberg warned there was a lack of statistical evidence about whether the nation’s mental health treatment program was heading in the right direction.

“We don’t have the data, we are outcome-blind,’’ he said.

“Mental health is a young person’s problem and yet we know very little about the mental health and welfare of young people.’’

Dr Hickie said Australia was still well ahead of the mental treatment curve globally but there were major challenges that needed to be addressed.

“The danger is when there is no serious quality care. The danger is prescribing on its own or inappropriately prescribing,’’ Dr Hickie said.

In 2016, The Lancet reported that researchers believed the rate of serious harm linked to antidepressants, including paroxetine, sertraline and citalopram, may be underestimated.

The study warned that the balance of risks and benefits of antidepressants for major depression did not necessarily provide an obvious advantage for children or teenagers. They found the drug fluoxetine may be helpful.

Psychologist Michael Carr-Gregg said antidepressants were a “perfectly valid form of treatment’’ and that misinformation, such as the drugs being addictive, did not help. He said there was significant anecdotal evidence to suggest that mental health problems among young Australians were common.

“The question is: are we talking about it more or is there an epidemic of depression?’’ Dr Carr-Gregg said. “And the true answer is we don’t know. Anecdotally, I would say that I’ve never seen so many kids with anxiety and depression.’’

Meg Charnaud, 21, a swimwear designer and ambassador for the West Australian mental health group Youth Focus, embarked on a huge change to her lifestyle more than three years ago after struggling with depression in high school. Between Year 9 and Year 12 she found herself skipping school, binge drinking, sleeping poorly, and was put on antidepressants.

In 2015 she embraced meditation and greater self-expression through her passion for clothes designing, which she says improved her mental health.

“I just found really good, healthy practices,’’ she said.

Ms Charnaud also cut her social media activities, which she said was central to the issue of her depression during her teenage years.