Flesh-eating bug infections nearing a record in Victoria

The mysterious flesh-eating bug epidemic infecting Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula now has experts seriously worried.

The mysterious flesh-eating bug epidemic infecting Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula continues to worsen, with the latest figures showing the disease has now overtaken last year’s record number of cases.

Last year saw 277 cases of Buruli ulcer, also known locally as Bairnsdale ulcer. Data released by Victoria’s Department of Health and Human Services shows 49 new cases were diagnosed in the past four weeks, and medical experts fear the total number of cases could push 400 for the year.

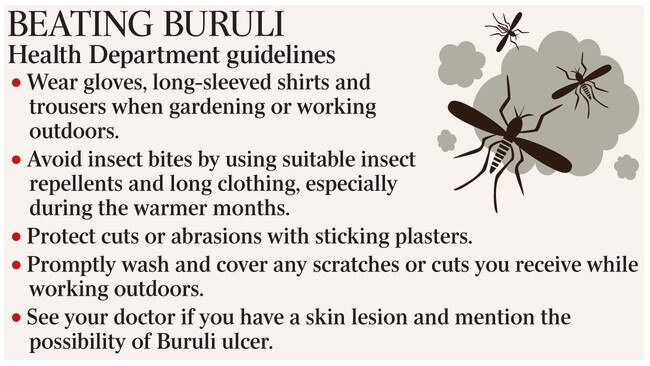

DHHS is warning people living in or visiting the Mornington Peninsula this summer to protect themselves from mosquito bites, at this stage the best hypothesis as to how the disease is spread.

The disease is caused by a bacterium called Mycobacterium ulcerans, which releases a toxin to cloak itself from the body’s immune system, allowing it to spread through tissue. It can leave people with permanent disfigurement and in worse cases require amputation of limbs.

Microbiologist Tim Stinear from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity said experts were gobsmacked.

“We’re in uncharted territory here,” Professor Stinear said. “It’s extremely alarming just how much this problem continues to escalate.”

He said he was certain possums were also involved in the spread of the disease. “Their precise role in transmission we’re still trying to work out, but they are definitely boosting the number of bacteria in the environment,” he said. “We only see human disease in areas where possum are carrying the bacteria.”

Daniel O’Brien from Geelong’s Barwon Health is treating about 80 patients and says several research projects are under way to try to discover essential information about the disease. “We’re preparing a questionnaire (for residents in affected areas) asking people about things such as their activities, the plants and animals around their homes, the clothes they wear and how often they are bitten by mosquitoes,” Associate Professor O’Brien said.

“We’re trying to establish the risk factors for catching the disease. Once you know the risk factors, you can design a public health intervention around reducing those risk factors and therefore reduce the disease.”

Residents of Mornington Peninsula and Bellarine Peninsula can expect to receive the questionnaire in coming weeks.

Bianca Ludowyke, a 31-year-old mother of two from Tootgarook on the Mornington Peninsula, says early diagnosis is the key. Her ulcer was initially misdiagnosed as an infected spider bite by Box Hill Hospital in May.

“The hospital didn’t know what was going on. I asked them to test it for Buruli ulcer but they wouldn’t. I was told to go away and come back in a few months if it hadn’t healed,” she said.

Eastern Health declined to comment on her case.

Ms Ludowyke’s ulcer spread and became severe before it was finally diagnosed correctly. She was put on a course of powerful antibiotics but still has months to go in her recovery. The scar is likely to be permanent.

Yet catching the disease was something of a blessing in disguise for Ms Ludowyke. It meant she knew what to look out for when her 15-month-old daughter Isla caught the disease soon after.

“With Isla, we were referred straight away to Dr O’Brien and got the treatment started early, so it never became a huge, open wound like mine. It’s now just a little mark on her hand.”

Infectious diseases physician Paul Johnson from Melbourne’s Austin Hospital supports the theory that mosquitoes and possums play a large role in transmission and says it’s worrying medical practitioners continue to misdiagnose the condition.

“It’s frustrating when people are being told to get to their doctor early and when they get there the doctor doesn’t know about it,” Professor Johnson said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout