GPs’ home delivery Covid-19 vaccine jabs for at-risk patients

GPs in outbreak areas are forking out thousands of dollars and driving to vulnerable patients’ homes to ensure they receive a vaccine.

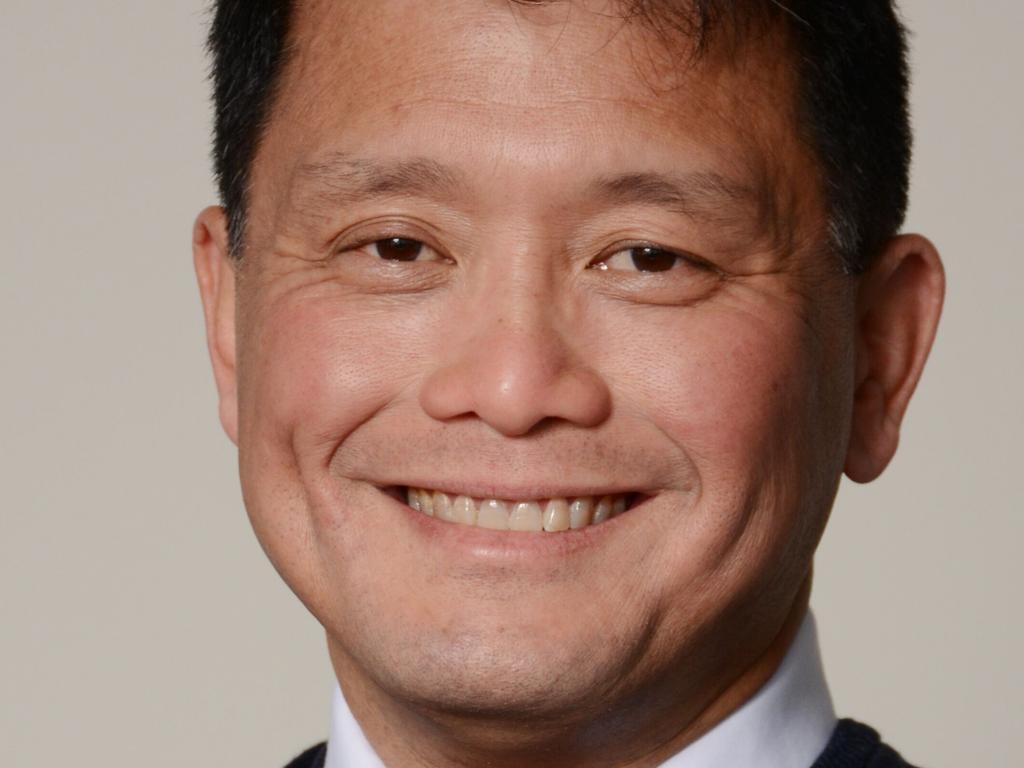

Jamal Rifi is exhausted. Already overworked, the Belmore Medical Centre practice owner spent Saturday driving around his area, delivering vaccines to vulnerable patients whose spots in the Pfizer queue would otherwise be snapped up.

The day before, Belmore Medical Centre’s allotment of Pfizer vaccines almost tripled, from 240 to 600. However, the local doctor did not list the additional 360 vaccines online.

Instead, Dr Rifi packed dozens of doses into a mobile fridge and set off to deliver vaccines to patients who could miss out.

“If I open up for further bookings online, the vulnerable will miss out. It’s the same as elderly people of non-English-speaking background,” Dr Rifi said.

When his practice opened for Pfizer bookings on July 9, the doses didn’t last long. Among those to book in were not just those in neighbouring areas but people from Sydney’s well-heeled north shore.

“I am still happy to vaccinate those people but with this uptake I am going to reserve it for vulnerable patients in the three hotspot LGAs,” he said.

That’s not his only frustration. Dr Rifi – and many other Sydney GPs – say the federal government’s pre-Covid-19 testing forms are so difficult to fill out that practices are wasting hours each day assisting patients.

Every day premiers urged people to get tested, which is relatively easy for those who attend drive-through sites, where test forms are pre-filled. But at a practice like the Belmore Medical Centre, which often sees 470 patients a day, each form has to be filled out, often requiring the help of staff.

“It’s not sustainable for us with such an increase in numbers. We need this form to be simplified so that someone with a slight command of English can fill it in,” Dr Rifi said. “Sometime evens English-speaking people struggle with it.”

Dr Rifi’s colleague, Stas Ulaszyn, shares his frustration. “The form is terribly worded. It’s vague in the way it asks for information, as well as asking for information which isn’t clinically relevant,” he said. “We could be much more efficient if we weren’t becoming admin secretaries for patients who might struggle to speak English.”

Neither Dr Rifi nor Dr Ulaszyn are blaming their patients, but they have serious questions for the government. “Both my parents are refugees,” Dr Ulaszyn said. “Half of us who are first-generation Australians have parents without a good command of English. We’ve gotten to a point where we’re asking patients to call a relative to have the form filled in. We’ve tried to take things into our own hands and come up with a QR code to fix the form. The government hasn’t given us any shortcuts.”

Staff say they could be vaccinating at least 25 per cent more people if it were not for the paperwork. “Instead, I think we’re turning away 10 to 20 cars each night. That’s a significant amount of people who go home and have to make a decision whether they will go join a queue at a hospital or stay concerned overnight,” Dr Ulaszyn said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout